Wildfowling dogs

When it comes to wildfowling having a dog is just as important as having a gun for Tom Sykes, and here he explains why.

Wildfowling provides many moments of sheer sporting magic and it has to be my favourite type of fieldsports. The early mornings may be tough, but these adventures can be incredibly rewarding as you can find yourself in wonderful locations on the foreshore. The unmistakeable sights, sounds and smells of the saltings on a crisp morning makes the early alarm call that little bit more bearable. A trip onto the marsh can become even better if you have the chance to bag a duck or goose for the larder, making your efforts worthwhile. Wildfowling can be a solitary sport, but I always have a trusty four-legged companion to keep me company. And the truth is that the majority of the time getting the quarry into the bag wouldn’t be possible without a good dog to retrieve it.

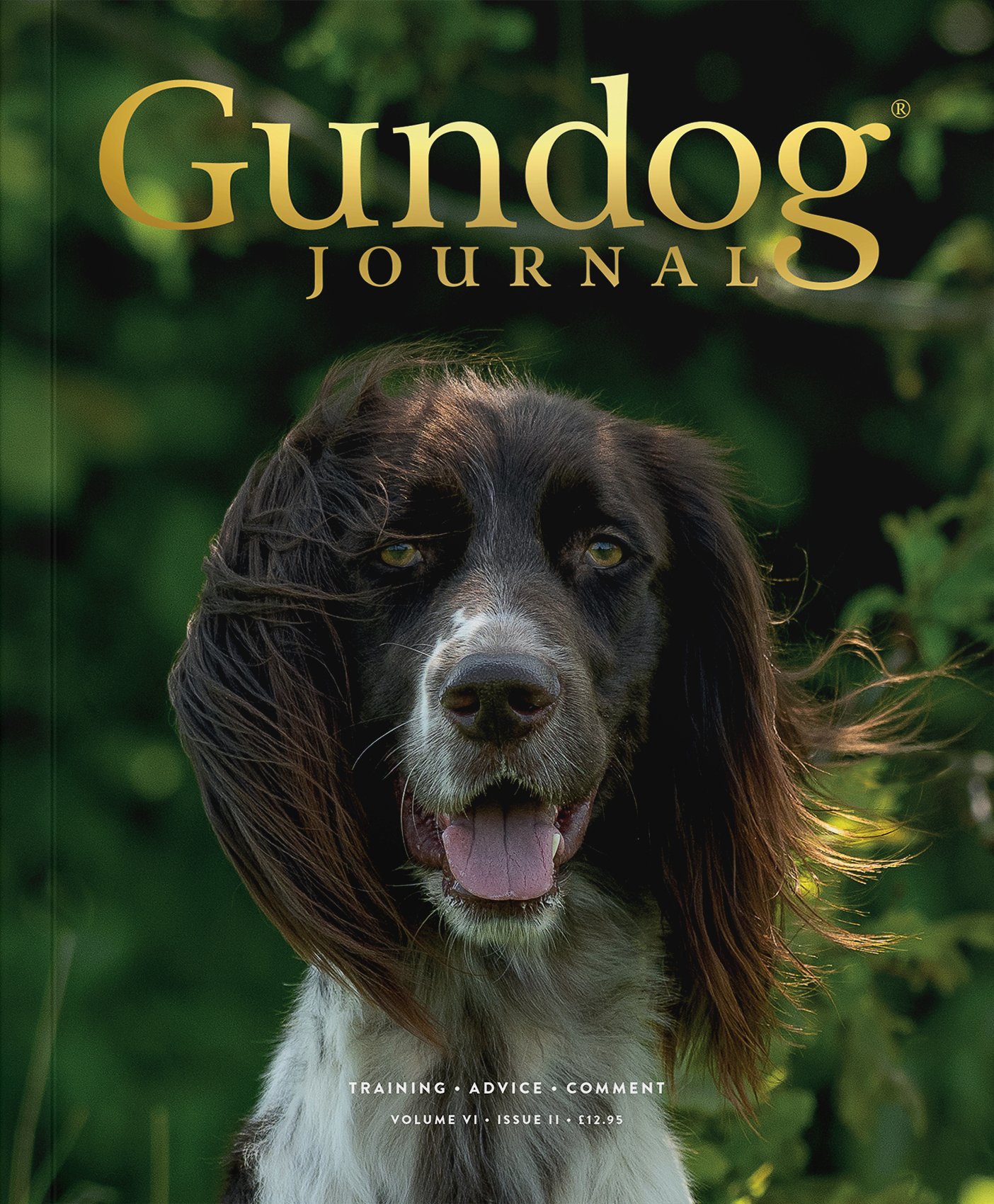

In fact having a capable gundog is as important as taking your gun when it comes to wildfowling. Yes, there can be instances where you can manage without a dog, but these are rare and very dependent on the situation. More often than not it would limit the opportunities for a shot as shot birds would need to fall in an area accessible by foot. I rely on dogs to retrieve the majority of my quarry as this allows me to make the most of the situations as dogs can access more areas without being in danger. I have had different dogs over the years which have joined me on the foreshore. My partner Charlie and I currently have a white labrador appropriately named Goose and a black labrador called Hugo. We will always have at least one of the boys with us when shooting on the marsh and, to be honest, I am sure they enjoy it even more than we do.

Dogs are essential for wildfowling and, through years of experience, I have learnt some very important lessons about taking them on the foreshore with me.

Dealing with the terrain and the cover

Foreshore landscapes can change drastically depending on the area of the country, with different locations harbouring varying vegetation and topography. The amount of cover and network of creeks can affect the difficulty of locating fallen quarry. Dogs are very important for sniffing out fallen birds. Even dead birds can be difficult to find if they have landed in cover or inside muddy gutters. There have been occasions when I have shot a mighty Canada goose and I would have struggled to find it if it wasn’t for the dog.

As well as negotiating the terrain and cover, a good dog is vital for retrieving birds quickly. Despite wildfowling being a somewhat solitary sport, there can be other ‘fowlers out and it is best if you can pick your birds quickly and efficiently to get them in the bag, but also to do this with minimal disturbance to the flight or other shooters. I like to pick up as I go along to reduce the risk of losing birds, even if I am sure they are dead in the air. We owe it to our quarry to pick them as swiftly as possible and this is best done with a good dog.

Working in the dark

Wildfowling retrieves can be made even harder by the unsociable hours and the lack of light at some of the best flight times. Goose’s light colour lends itself to working him in the darkness as I can see his rough outline as he works. This is where a good hunting dog will outshine others. It is difficult to give dogs clear commands when you can’t see one another. I usually rely on the fact that Goose and Hugo probably know a lot more than me. I have trained them to work well and hunt the area with little guidance from myself which I believe is essential to pick birds in the dark. I have always trusted my dogs when they take a line even if I was sure the bird was dead. It is easy to have misjudged the fall of the bird in the dark, especially when blinded by the muzzle flash.

Shooting over water

My favourite type of wildfowling has to be tide flighting ducks over decoys, and not just because wild ducks are fantastic food for the table. Tide flights can occur at different times of day depending on the phases of the moon which affect the tide height and time. I commonly set my ambush in creeks off the main channel or river, where ducks will shelter as the incoming tide pushes them off the mud banks and faster flowing areas. These side creeks are also safer places to work a dog as the current is usually not as strong and they aren’t as wide, meaning that it is easier for the dog to get back onto dry land.

Tide flights work best when the incoming tide is accompanied with strong winds. The wind helps to stir the ducks and force them to look for a better location to shelter from the elements. Ducks will predominantly fly over the water as it is where they feel safe. This means the majority of the shots taken on a tide flight are over the decoys resulting in shot birds splashing down into the tide. Most downed birds that land in the water are irretrievable by hand as the foreshore mud is often treacherous to stand on and the fast-flowing water can soon be too deep to wade in due to the increasing volume of water as the tide pushes in from the sea. A trusty dog is a must in these situations.

Blind retrieves

Shot birds don’t always land in the water when wildfowling and ducks and geese can often end up on the other side of the creek and out of sight. This is another instance where a good dog is valuable. Crossing creeks is often too dangerous for humans because we are a lot heavier in the first place and all the weight is on two legs and not four. Therefore it is commonly up to the dog to find the bird with no assistance from the handler other than commands. Goose has become one of the best dogs I have ever had for the foreshore. He seems to be in tune with the surroundings and has a fantastic ability for marking downed birds. His experience in the field has made him a great dog for understanding the situation.

He is often set back behind my shooting position in a hide to conceal his light colour and protect his hearing from the shooting. Despite being covered by netting he always seems to take the right line when called up for a retrieve. It is important to have a dog that will cross water and take commands at distance. It is also important to have a dog that will hunt well when out of sight, the same as when retrieving in the dark. Goose is often sent for birds that have dropped out of sight over the next banking, which can be runners. He will hunt the ground and more often than not reappear with the bird in question.

Multiple birds

Shooting multiple birds at once can make picking-up difficult, especially when over water. Unlike your typical driven day, wildfowlers don’t have the advantage of a picking-up team to sweep up. We are self-sufficient and need to mark birds down to be picked. This can be harder when shooting more than one bird at once. Although potentially hard enough on dry land, this can be made harder when shooting over water. I will always assess the situations as they appear and work out if it is wise to take

a shot and, if the opportunity arises, whether to shoot more than one bird.

I have seen other fowlers in the past desperately trying to get the dog back out for a second or third retrieve as fallen birds drift away with the current. This is not a situation you want to find yourself in as your hard-earned meat washes away. I will shoot multiple birds if the situation allows. For instance where there is slow moving water or where I am sure the birds will land on the banking or be washed in towards dry land by the wind. Two dogs can be good in this situation but only if they are happy to work independently of each other.

Divers

Pricked ducks and geese can be a challenge to retrieve off the water for even the most experienced wildfowling dogs. Although geese can dive, the more common species to have issues with diving has to be ducks. They have a tendency to dive just as the dog gets within striking range. They will reappear and try to evade the dog by staying low in the water. This can make them very difficult to retrieve as they can disappear in the waves and ripples of the water. Goose and Hugo have adapted the technique I call snorkelling. They will dive their heads under water as the duck dives and can often grab the diving duck from underwater.

Having the ability to redirect a dog mid-water retrieve is very useful, as ducks can often resurface behind the dog and they will often need guidance to help them get back on the right line. Although Goose and Hugo are good at retrieving diving ducks, I will try my best to safely cripple stop the duck on the water by giving them another barrel to dispatch it. This is more humane for the quarry and reduces the time it takes to pick the bird. Divers can take a long time to retrieve and can even travel a long way in dangerous water. It is important to minimise the risk to the dog in these situations, a speedy retrieve can also mean you can get back to the action faster as the number of chances can be very slim on a foreshore flight.

Foreshore dangers

Marshes are notorious for being dangerous places to venture for the ill-prepared. This is very relevant to dogs too. The most common problem for dogs has to be fast flowing water. Numerous wildfowlers over the years have lost dogs in these dangerous conditions. It is important to have a dog that will listen to commands to ensure they stay safe. I will try to avoid dangerous situations, but even calculated risk taking can take a nasty turn if the variables change.

It is important to have a dog that won’t run in when shooting near dangerous water. A wing-tipped duck or goose can head a long way out into such water which can be an issue when a head strong dog decides to follow suit. Tethering a dog down in these situations can be a good idea, even if you have trust in your companion, it is better to be safe than sorry. It is also essential to have a dog that can be called off a retrieve if required to keep them safe. Training has instilled this in Goose, but not all my dogs have been as well trained in the past.

I had a few horrible situations in my early wildfowling career when my then ‘fowling partner was a rather charismatic but very head strong springer spaniel, Fred. Despite being a very good dog, Fred aimed to please and often ended up in situations I didn’t want him to be in as he was determined to retrieve everything I shot. I had a few occasions where he swam after pricked ducks out of the side creek and into the full flow of the incoming tide. I was fortunate that despite doing this a few times, Fred seemed to have more lives than your average moggy and would normally return, with the bird! Despite Fred’s luck, many dogs do not share the same fate and a few on my local marsh have succumbed to the current and never been seen again.

Total teamwork

All my dogs have been great partners with whom I have shared a wonderful bond. We understand the task at hand when out on the marsh and work well together to get the job done. Although we occasionally end up with our wires crossed, I wouldn’t be without them. They make the whole adventure special with every trip on to the marsh and are an essential part of my wildfowling.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

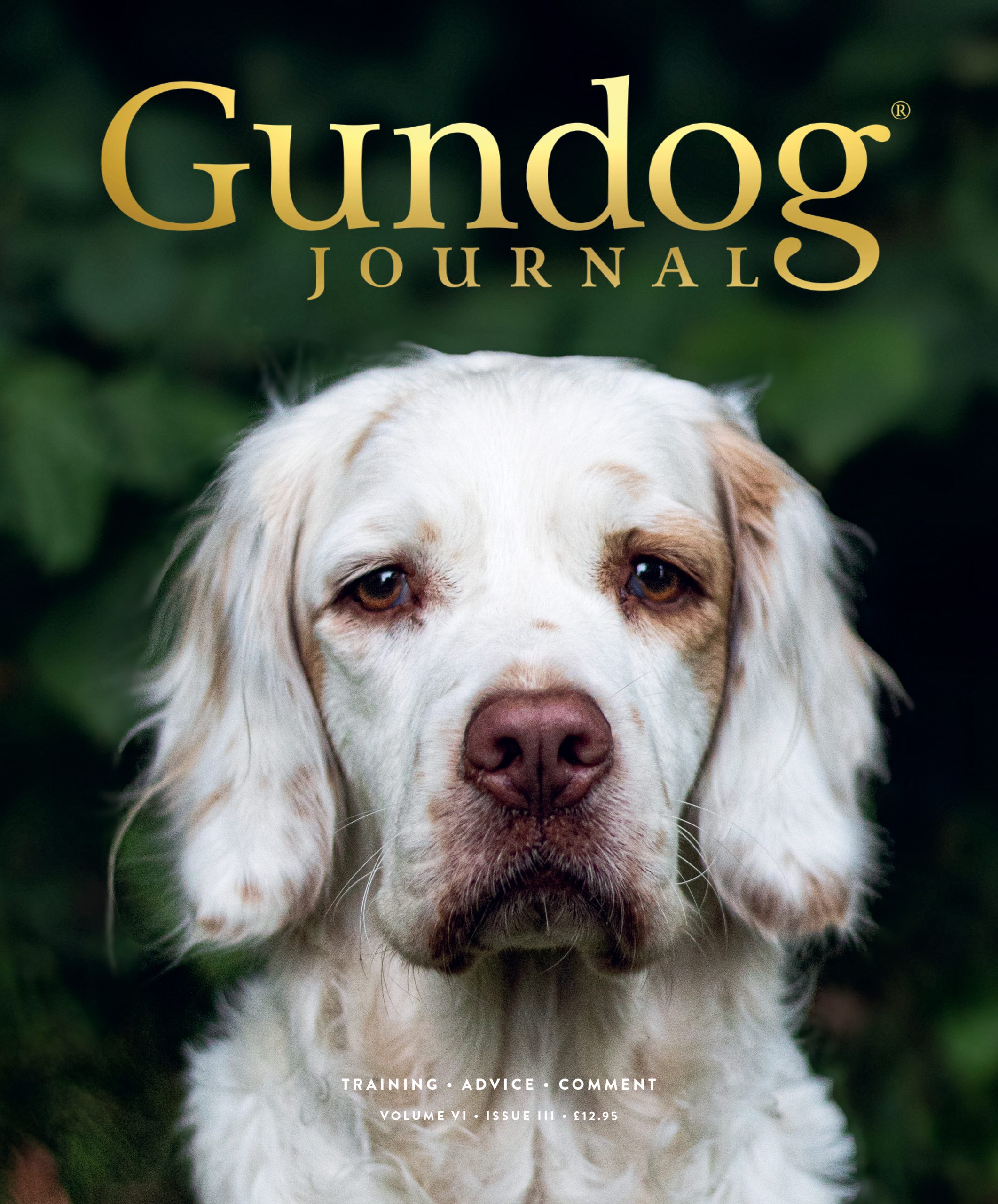

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.