Keepers’ dogs

As Liam Bell explains, a gamekeeper’s dog needs to be an all-rounder, but its value is not judged purely on performance in the field.

We gamekeepers have dogs to work them, but we also have them as companions. In that respect I suppose we are no different from any other type of gundog owner, but I would be happy to be corrected on that.

Where I’m sure we do differ from other dog owners, is in the variety of the things we ask our dogs to do. Very few keepers have the luxury of being able to keep a dog on ice, to be able to put one to one side for retrieving on shoot days or to be able to keep a dog solely for following up wounded deer. Rightly or wrongly, we expect our dog to be a Jack of all trades, and whilst true all-rounders do exist, and most of us end up with dogs that are fairly good at most things, it is rare to own one that is good at everything.

If I had to list my dog’s duties in an order of importance, I’d struggle. Everything they do is important; it just depends on the time of year. In spring they are due a certain amount of downtime after the physical rigours of the season. The older ones need a few weeks to recharge their batteries, and to put some condition back on if they have had an especially hard season, and to rest their aching limbs. These are rather similar needs to those of their gamekeeper owners. Although I should add, there aren’t many of us over the age of 45 who suffer from a lack of condition.

So, what are the different tasks we keepers expect our dogs to perform with a degree of competence? We may not be looking for breath-taking style in their performance but competence is more valuable when there is a job to be done…

Tracking deer

I have one dog who is busy in spring while the others are having their downtime, and that is my steadiest labrador. It isn’t very strenuous work, and thankfully he doesn’t have to do it very often, but when he does do it, he does it well. I use him for tracking deer that have run on after the shot (and who aren’t immediately visible), and to check a shot site for blood and clipped hair if there is an unexplained miss. Often it is really just to confirm that a miss is actually a miss, or if he does find something, to follow up the blood trail and get him to lead me to the dead or injured animal.

I use a labrador because my spaniels are too erratic and less good at taking a line. He rarely stalks with me, but I know he is only 30 minutes away if I need him. Which incidentally is about the correct length of time to leave a wounded animal before following it up. Following up sooner risks bumping the animal further, and in turn making it harder to find. Better to leave it to stiffen up and die where it is. Which isn’t usually that far away from where it was shot, and is exactly what has happened to nearly all the animals I have had to get the dog to track for me.

Like so many gundogs, he knows what he is looking for as soon as I take him to the shot site. How does he know? My clothes, my rifle, the stalking sticks, the time of year? A combination of all of these maybe? Whatever it is, he doesn’t look at a pheasant, won’t hunt a rabbit and concentrates solely on deer.

A gentle walk with him to where I think the animal was when I shot at it, is about as much as I do. I leave the rest to him. He marks blood and hair, will follow a blood trail and seldom fails to find. Another scenario of course, is double checking the site with the dog after an unexplained miss and finding nothing. All I have to do then is go back to the range and check the zero before going back out.

Dogging-in

Late summer and early autumn are dogging-in time, but dogging-in isn’t, as some people assume, a mad dawn-until-dusk pheasant chasing session. Pheasant poults spread out as they mature (as do all birds and mammals), and when they do some of them quite obviously head away from where we want them to be; towards roads, and villages and horror of horrors – towards our neighbour’s boundaries

What the dogging-in does is turn and steer the birds back in the right direction. For this you need a steady, biddable dog that is happy to watch poults and adult birds running in front of it, a dog that is keen enough to gently bump them out of heavy cover, and at the same time one that you can trust to go in and flush them hard when asked, without pegging them. It’s not too hard to do this when the birds are grown and well on the wing. But equally it’s not particularly easy when you are moving poults that are unsure where they are going.

Shoot day dog

When the season starts my dogs are reasonably fit, thanks mainly to the dogging-in, but they are still carrying enough weight to see them though a season’s beating. And this is an important factor which shouldn’t be overlooked. The season is hard on the dogs. Of course they love every minute of it but they mustn’t be too lean at the start.

A keeper’s shoot day dog needs to be steady. It needs to be an honest dog, and by honest, I mean a dog you can ignore for most of a drive without having to worry where it is or what it is up to. It needs to be a dog that doesn’t chase running game, that won’t run riot in a game crop, that doesn’t need to be on a lead on a flushing point or need over-handling during a drive.

It takes time to get a dog up to standard, but it’s not impossible (and I should quantify this by saying that whilst most of mine have been OK, I have owned one or two nightmares that I couldn’t really do anything with) and dogs being dogs they will soon learn what they can and can’t get away with.

A case in point being an eight-year-old cocker bitch I have in the kennels at the moment. She will only run in when she sees me reach for my horn at the end of a drive. Has she learnt it, did I teach it to her by accident or was it something I let her get away with a few times that’s now been passed by her as acceptable?

At the end of a drive I might get my dogs to pick a few birds around the pegs. Again, they need to be on best behaviour with no squabbling with the guns’ dogs or pinching their birds. They need to bring any birds they find straight to hand, and they must be happy to come back as soon as they are called when I need to get to the next drive. This is simple retrieving, nothing too taxing, but nevertheless another string to their bow and a bit of help for the picking-up team.

Companionship

Finally, and in no way any less important than the reasons for keepers owning dogs given above, we keep them as companions. Cold nights foxing, hours of lone working and home life (in the case of student keepers and gamekeepers who live alone) are made all the more bearable by the company of a dog, regardless of its colour, working ability or breed.

My constant companion when I was in my teens, and an underkeeper living in a caravan on the side of a bog in mid-Wales, was a tri-coloured bitch of mixed parentage. Many were the nights she and I sat listening to the rain lashing down, while the wind rocked the caravan back and forth as we tried to get a picture on our portable TV.

She had many failings; a suspect mouth, a tendency to yip when excited, frustrated or taking a line on a runner, a weakness for farm cats and questionable manners when in company. Her working abilities were far from perfect, but we understood each other, and her strength was the company she provided on those long winter nights.

On reflection, a far more important quality than is sometimes appreciated when we aim for a standard that is rarely achievable, and look on enviously as our neighbours’ paragons of canine obedience stop on the whistle and go back another 200 yards, when we have a friend sat at our feet.

Liam Bell is the chairman of the National Gamekeepers’ Organisation.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

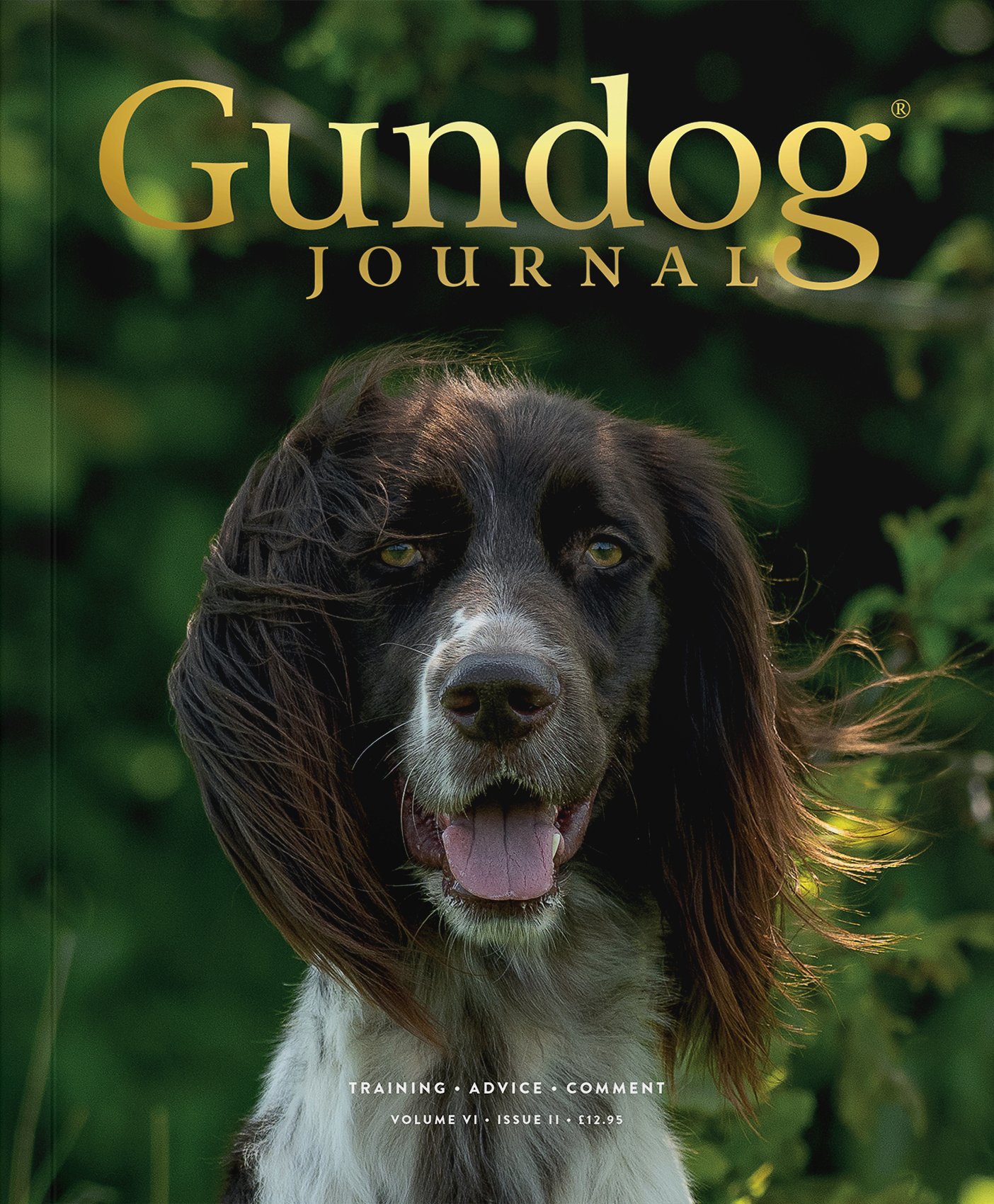

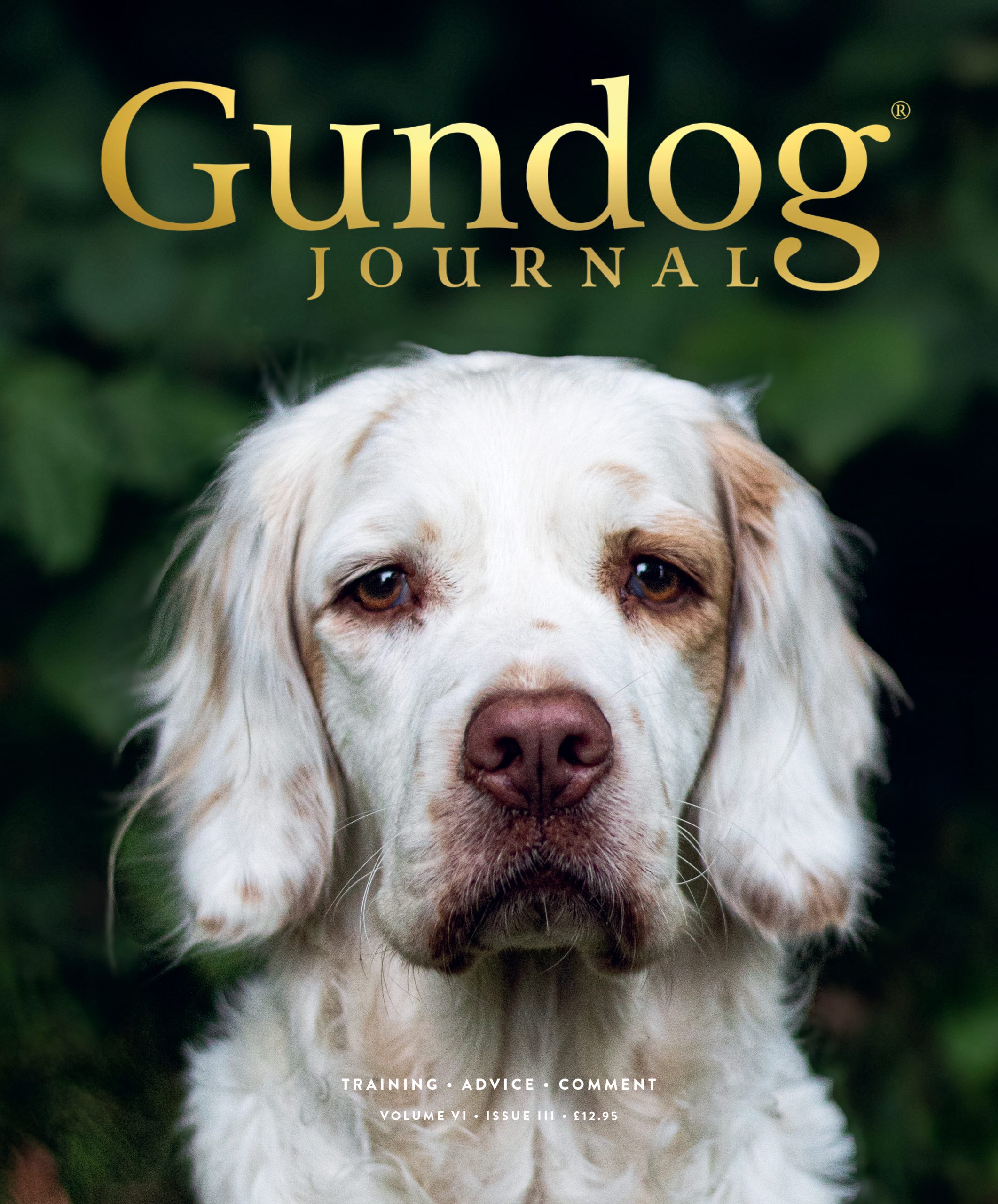

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.