Time to make a plan

At the end of the shooting season, you might be forgiven for thinking that the busiest time of your gundog’s year has passed, says Field Editor Ben Randall, but in reality some of the most important ‘work’ happens during the spring and summer months

Without a doubt, October to February is the most exciting time to be out with our dogs in the field, but if we want to ensure our working companions continue to progress year on year, it is imperative that we make the most of that so-often-underused 6–8-month period when the breeks stay in the cupboard.

One of the greatest errors I see as a professional trainer is this ‘until next season’ mentality amongst gundog owners. It’s a bit like putting your gun away in the cabinet on 1 February, not touching it throughout the spring and summer until your first day of the next season, and still expecting to shoot well. The nature of activity with your dogs during this time is equally important; infrequent training sessions with no real structure, element of consistency or end goal do little for a dog’s progress, but can mean weak areas or issues are not addressed and are instead compounded.

A Well-Earned Rest

Ater three or four months of hard work, I always give my dogs a rest in February, letting them completely relax and switch off from their usual working or training regime. They are allowed to run freely around the paddock at home and play with each other in a controlled environment.

During these few weeks, the focus is on regaining the dog’s condition. The spaniels in particular are often a little sore after their enthusiastic bramble-bashing and working in thick cover, and I’ll look to put a little more weight on the dogs as they often become very fit when out working regularly. Each dog is different, but I generally maintain food volumes administered throughout the season for the whole of February. As they are less active, the dogs soon start to put weight on and get a good shine back in their coats.

By March, then, the dogs have had a chance to relax and recover and they’re ready to get going with their off-season training.

Making a Plan

During the shooting season, we all notice areas in which our dogs can improve. These should be the focus of our spring and summer training.

Because of my job, I am able to address any issues as and when they arise, but not everyone is able to do this.

Of course, a major issue such as ignoring the recall completely, aggression, or running into a drive must be addressed and resolved in training before a dog is taken into the field again – for obvious reasons. Most likely, however, you will begin noticing sloppiness or bad habits gradually creeping in – the sort of things that do not cause huge alarm but gradually worsen over the course of the season.

It’s a good idea to keep a note of all the things that have gone wrong whilst out in the field, even if they seem minor and quite insignificant at the time. The smallest of things can quickly develop into frustrating habits if left to manifest over several seasons.

I ask my clients to keep a record of what has happened and then when it comes to drawing up a training plan, we address each point systematically, asking: Why has it happened?; How has it happened?; And is it me or is it the dog? It’s worth taking your time when considering each of these questions – time invested at this stage can save you weeks in the training paddock.

Once the cause of each issue noted down has been determined, it’s time to draw up a training plan. With my dogs I conduct two short, sharp sessions a day, each of which have a specific focus. A session typically lasts for 15 minutes, always ending on a positive note, and progress is tracked as we go.

Dogs thrive on structure and routine, it’s how they learn, but it is important to keep training sessions interesting and stimulating to prevent boredom. Regardless of progress, I therefore give a dog a break from training for three or four days every 4–6 weeks, dependent on the dog’s nature and how easily it loses focus. It’s important to remember dogs are not robots and too much for too long can be counterproductive.

Many problems stem from working our dogs in a fashion they are not used to in training. We can set up situations whilst training our dogs to increase the likelihood of success, but of course we cannot always do this on a shoot day, and our dogs inevitably begin finding success themselves. As a result they can start to believe in themselves a little more than they believe in their owners. It is this trust and belief that ‘if I listen to Mum/Dad, I will find more’, we must endeavour to instil.

The Stop Whistle and Final Recall

As the shooting season progresses, it’s not uncommon for a dog to start becoming a little sloppy on the stop whistle and recall.

Most of us train our dogs to do both of these things using reward-based methods; the dog learns that if it stops promptly or returns to us upon the command, it will be directed to a bowl of food at mealtimes, or something exciting to retrieve. However, during the season, these often turn into negative commands, meaning ‘stop, because there’s a problem or you’re doing something wrong’. We want a dog to associate the stop whistle and recall with positive experiences – a dog that obeys a command because it wants to work with you is much better than one that obeys a command because it has to.

For the stop whistle, go back to basics and begin stopping your dog on the way to its food at mealtimes, just as you would when first introducing the command to a puppy. To make sure the dog sits promptly without delay, position yourself between the dog and the food bowl and be ready to step into the dog’s space as you blow the whistle gently. Do this four or five times in a training session. Remember: quiet whistle work is key. Then progress onto dummies and gradually increase the difficulty of the exercises.

To sharpen the recall, it is a similar process – give your dog an incentive to return to you as quickly as possible, e.g. so that you can send it for a retrieve that you have hidden. If your dog is taking too much time or in the habit of continuing to hunt after the recall, be prepared to get your running shoes on and quietly catch it up – the dog must learn that you can and will reinforce commands.

Keeping Them Close

This is of particular importance to those who work their dog(s) in the beating line or do a lot of walked-up shooting. During training we can drop balls, dummies and cold game around our feet, and the dog will find things close by with frequency, but we cannot set up such situations in the shooting field. If not kept close, a dog will soon learn that it can also find game itself, further away, and without any help from you. It is what is known as ‘pulling on’ and is a common issue, especially among the spaniel breeds.

Happily, there’s much we can do as handlers during the off season to remind the dog why it should stay close to us whilst working. For the next eight months, ensure the focus of any fun centres around you, and the dog only finds things to retrieve when it is near to you. Avoid ‘walks’ where the dog is allowed to free run and hunt and find things independently. Consistency is crucial here – weeks of good work can be undone by a careless 30 minutes where you allow the dog to find entertainment on a ‘self-employed’ basis.

Out of Season Opportunites

There are, of course, sporting situations throughout the spring and summer months that can offer the perfect opportunity to train your dog in a new and exciting environment.

Dog-friendly clay grounds, for example, are a great place to practise steadiness with a peg dog that has become a little too excitable over the course of the season. Speak to the ground owner and ask if you can stand far back and out of the way. The gunshot, movement of the clays and number of new people all serve as a distraction, and you are in a position where you can focus solely on the dogs. In the past I have used such a scenario as a mini simulated drive, where my dogs will sit steady and perhaps be rewarded with a few simple retrieves if they are calm and well behaved.

Many game Shots will also enjoy a few days of pigeon shooting during the spring and summer months – another prime time to teach your dog that not everything that falls from the sky is theirs to pick up. Be very selective on these days and focus on keeping the dog relaxed.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

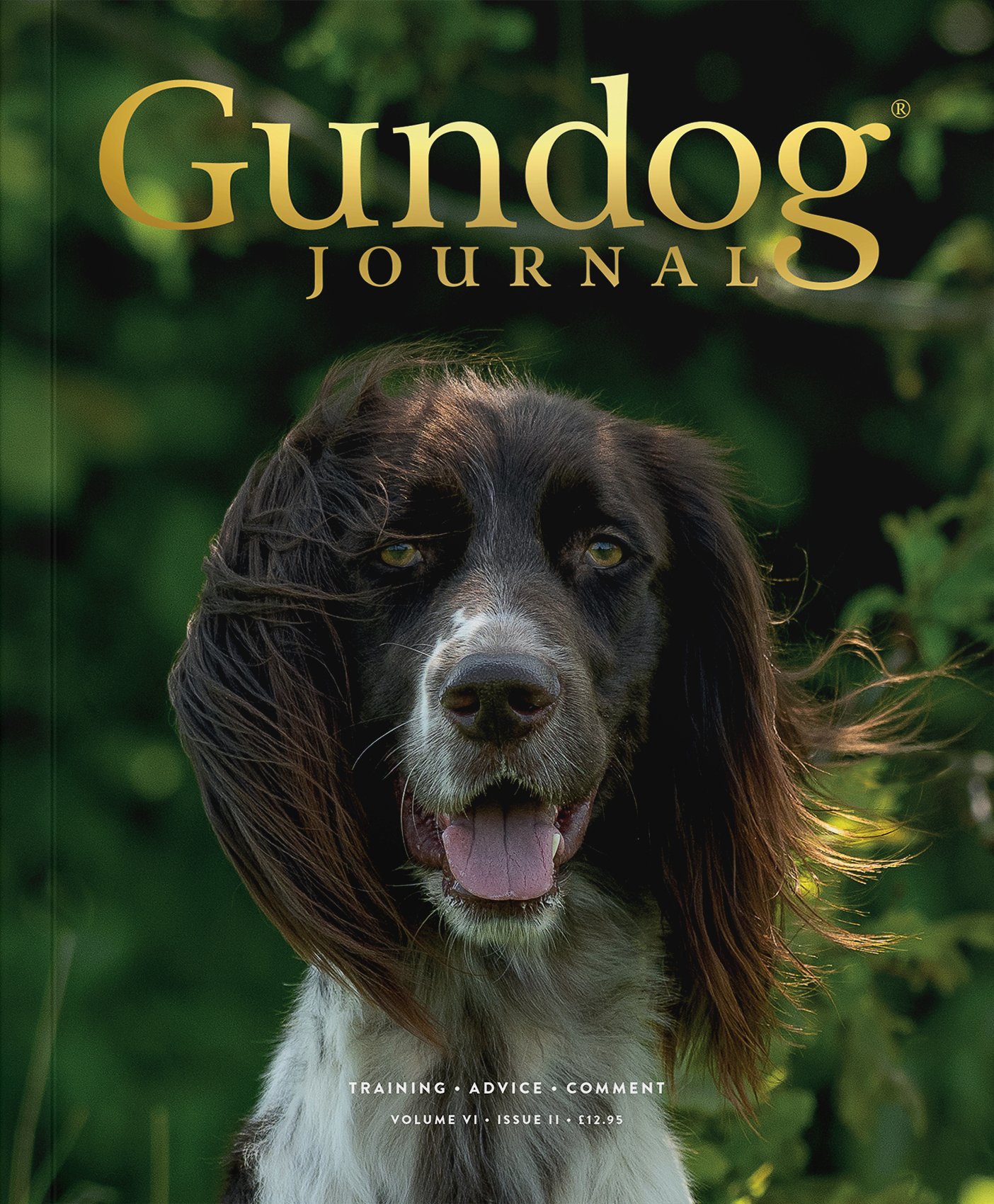

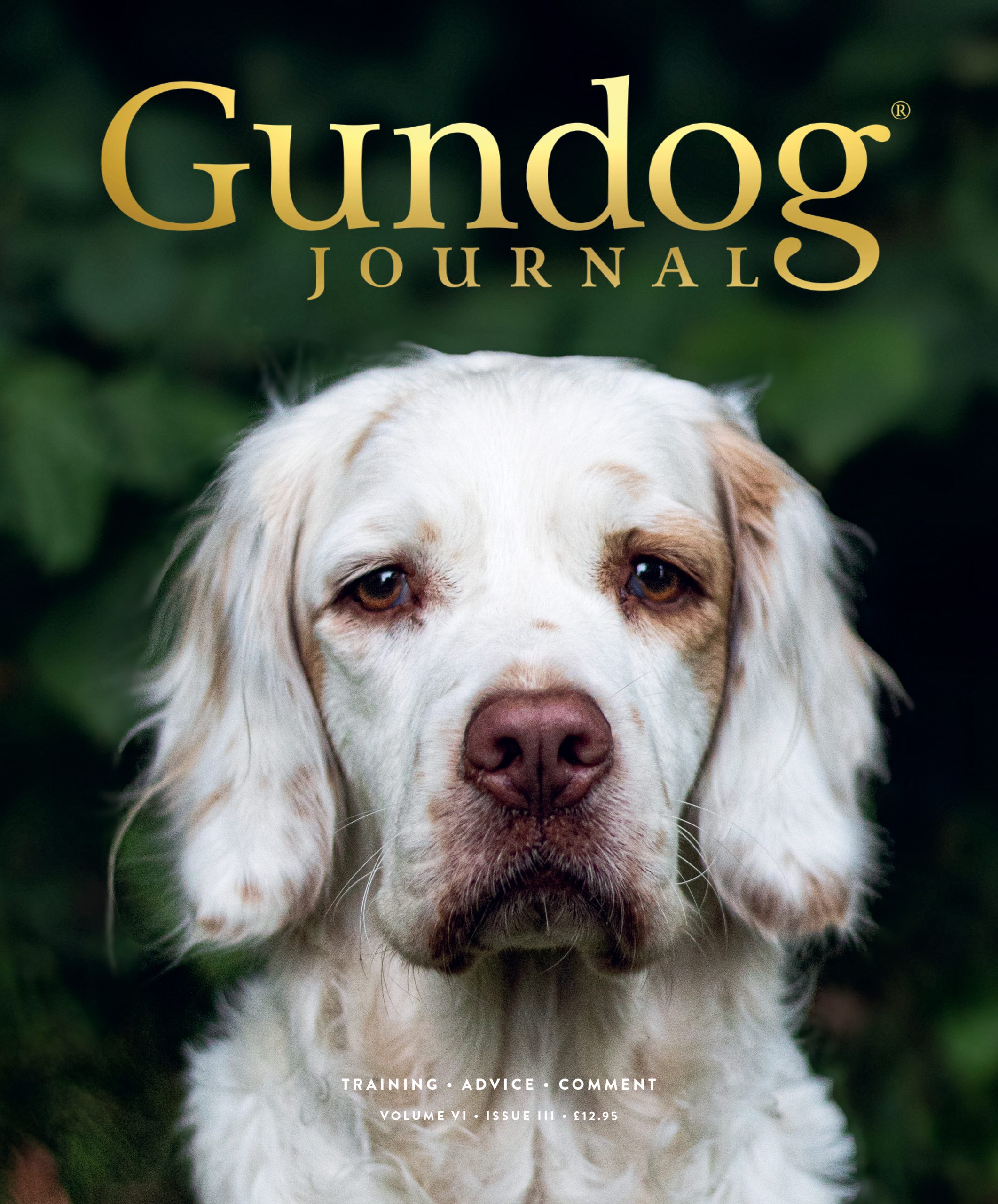

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.