Let’s talk scent

Understanding how our dogs use their noses is crucial. But equally important is knowing what we can do to help them put that marvellous asset of theirs to best use.

Dogs’ noses are remarkable things. Mysterious, too; perhaps we’ll never fully understand the ins and outs of how they work. A quick search online and you’ll find a range of figures (anywhere from 1,000 to 100,000 times) quoted for just how much more acute their sense of smell is than ours. There seems to be a lot of guesswork. But one thing is for certain: dogs – especially working dogs – rely on their noses much more than they do their eyes or their ears. And if we fail to appreciate this when training and working them, we put ourselves at a huge disadvantage.

Understanding how our dogs use their noses, then, is crucial. But equally important is knowing what we can do to help them put that marvellous asset of theirs to best use. And to do this, we must be familiar with the basic principles of scent.

WHAT IS SCENT?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines scent as “a trail indicated by the characteristic smell of an animal and perceptible to hounds or other animals”. In the shooting field, we want our dogs to pick up the specific scent of our quarry, whether that be for the purpose of flushing for the gun, or retrieving shot game.

Scent is caused by minute droplets of moisture which emanate from a creature’s scent glands. Perhaps the bestknown type is adrenaline, secreted when an animal is disturbed and provoked into sudden action. In addition, shot birds might emit a blood scent. And this might be spread across an area or be virtually non-existent, depending on a number of factors that are considered later in this article.

HOW DO OUR DOGS PICK UP SCENT?

Dogs hunt for scent in different ways. This is particularly noticeable when comparing breeds. Spaniels, for example, will typically hold their noses close to the ground whilst hunting. Retrievers, HPRs, pointers and setters, on the other hand, will hold their head higher when hunting – they are searching for air scent. To complicate matters, when rain or a heavy dew is followed by warm weather, it is not uncommon for dogs which normally favour hunting for ground scent to lift their heads when hunting, as the scent evaporates and rises upwards.

Both methods can be effective, but, in my experience, those dogs which hunt with their noses glued to the floor, and cover ground very quickly, can run over game and struggle to hold an area as well as a dog working at a slower pace and in a more methodical manner – as is the case with most dogs hunting air scent.

INFLUENTIAL FACTORS

There are many variables which can and do affect how easily our dogs will find scent and hence our quarry. Below I have highlighted a few which I have encountered.

Weather:

Temperature, humidity and precipitation all play a part, and can either improve scenting conditions or make things difficult. Hot, dry weather, heavy rain, snow, and high winds typically render scenting conditions poor.

I imagine that in very dry weather, the scent spores have little to attach themselves to in the way of moisture and so do not hold in an area for long. On the other hand, precipitation will have the effect of diluting or ‘washing away’ scent. Conversely, frost seems to lock up scent; a dog may find it very difficult to track scent on frozen ground first thing in the morning, but if it begins to thaw, they tend to have more success.

Wind also plays a big part. High winds seem to stop scent from lingering as much in a concentrated area. It is crucial that the handler is aware of the wind direction, its strength and any features which might change its course or characteristics. We must think about what the wind is doing at the position of the fall, or where our dog is hunting – are you in a sheltered spot or are you very exposed? Is the wind being channelled by a hedgerow, woodland or another feature? Has the scent drifted on the wind and, if so, where is your dog most likely to pick it up? There’s a lot to think about.

The best scenting conditions are presented in the absence of extreme conditions. I know that if there’s a fair bit of dew on the kennel doors on a morning, and it’s mild and not too windy, the dogs will have a much easier time finding things.

Environment and distractions:

In my experience, different cover types will hold scent to varying degrees. Sparse grasses, for example, do not seem to hold scent as well as thick root crops or dense foliage.

Distractions by way of other smells and scents are also worth considering. Our dogs will encounter a plethora of other smells with those incredibly sensitive noses of theirs. You might, for example, be hunting in heather in full bloom, or in woodland with lots of wild garlic or rotting leaf litter. Finding and tracking scent can be difficult in such cases.

Distractions might also exist in the form of other birds and animals, and humans. It might be that a fox, deer Photograph: Jo Shepherd or hare has recently been in an area, or a whole team of Guns on a driven day have walked over an area with their dogs before you arrive to search it.

The fall:

From my experience, how a shot bird falls to the ground will also affect how much scent it leaves. If a bird falls to the ground in a whirl of flapping wings and ruffled feathers, and causes disturbance to surrounding vegetation, I find the scent tends to be spread over a wider area, making it easier for a dog to detect. Conversely, scent of a bird that has folded neatly and plunged through cover, causing very little disturbance to surrounding vegetation, will be much more localised and hence harder to find. The same principle might apply to game we are searching for to flush. A rabbit which has sat tight in rushes all night, and has stayed in the same spot whilst the wind passes over and around it, will be much harder to find than one that has been on the move, disturbing cover and leaving a scent trail.

Enhancing Your Chances

So there is much to consider, but there are ways in which we can help our dogs put their noses to best use.

Marking:

Firstly, you must be able to mark accurately. Use surrounding features (e.g. trees, hedgerows, tramlines, fence posts, etc.) to help you remember where a bird has fallen, and learn to judge range. Poor marking translates to a lot of guesswork and often limited success in finding what you’re looking for.

Holding the dog in an area:

Once you have established an accurate mark, being able to hold your dog in a specific area (i.e. keep it hunting over a particular patch of ground, without straying) can be very useful and save a lot of time. This is something you can practise in training. Teach your dog the hi-lost command with food at an early age, and then dummies later on. And only use the command when they are very close to their target.

Trust:

This is crucial. Your dog should believe in your commands. This confidence comes from success (finding food, balls, dummies and game during training) as a direct result of following your instructions. As soon as your dog believes that he/she is better off ignoring you and simply acting on their own accord, you have lost control. In the shooting field, or at a field trial, you cannot set up situations like you can during a training session, so there will be times when your dog does fail, even after following your commands. It is important to top-up confidence levels during the season with training sessions for this very reason.

Know your dog:

Of course, you must also trust your dog, and know when not to interfere and just let it do its own thing. It is important not to over-handle your dog(s). From watching my own dogs work, I know if they are onto something that I might not be aware of – an apparently hard-hit pheasant might have run 100 yards without me knowing, for example – and I trust that they will do the right thing. You must learn to read their body language and then act accordingly

Food For Thought

Now I’m going to throw a spanner in the works. I believe that our dogs also encounter another scent type in the shooting field – one that is directly related to shot quarry when walked-up shooting.

I call it shot scent. Simply put, in my opinion, a pillar of scent is left at the point of impact where the shot column collides with the quarry – resulting in two areas of scent that a dog will come across. The other, of course, being where the bird falls into cover/hits the ground.

Time and again I have watched as dogs stop in their tracks and begin hunting enthusiastically as they reach an area 10 or 20 yards short of where a bird has actually fallen. I have seen this happen with hundreds of dogs, and this additional area of scent always seems to exist at the point of impact. My theory is that the dogs pick up on the scent of gunpowder from the shot which has hit the bird and deposited on vegetation below the point of impact. Or perhaps a glut of scent is dispersed from the quarry when it is first hit?

This can be very confusing for both dog and handler and I have no doubt that it is the cause for many a dog’s failure and subsequent elimination in field trials. In the shooting field, it really tests that trust between dog and handler and highlights the vital importance of accurate marking.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

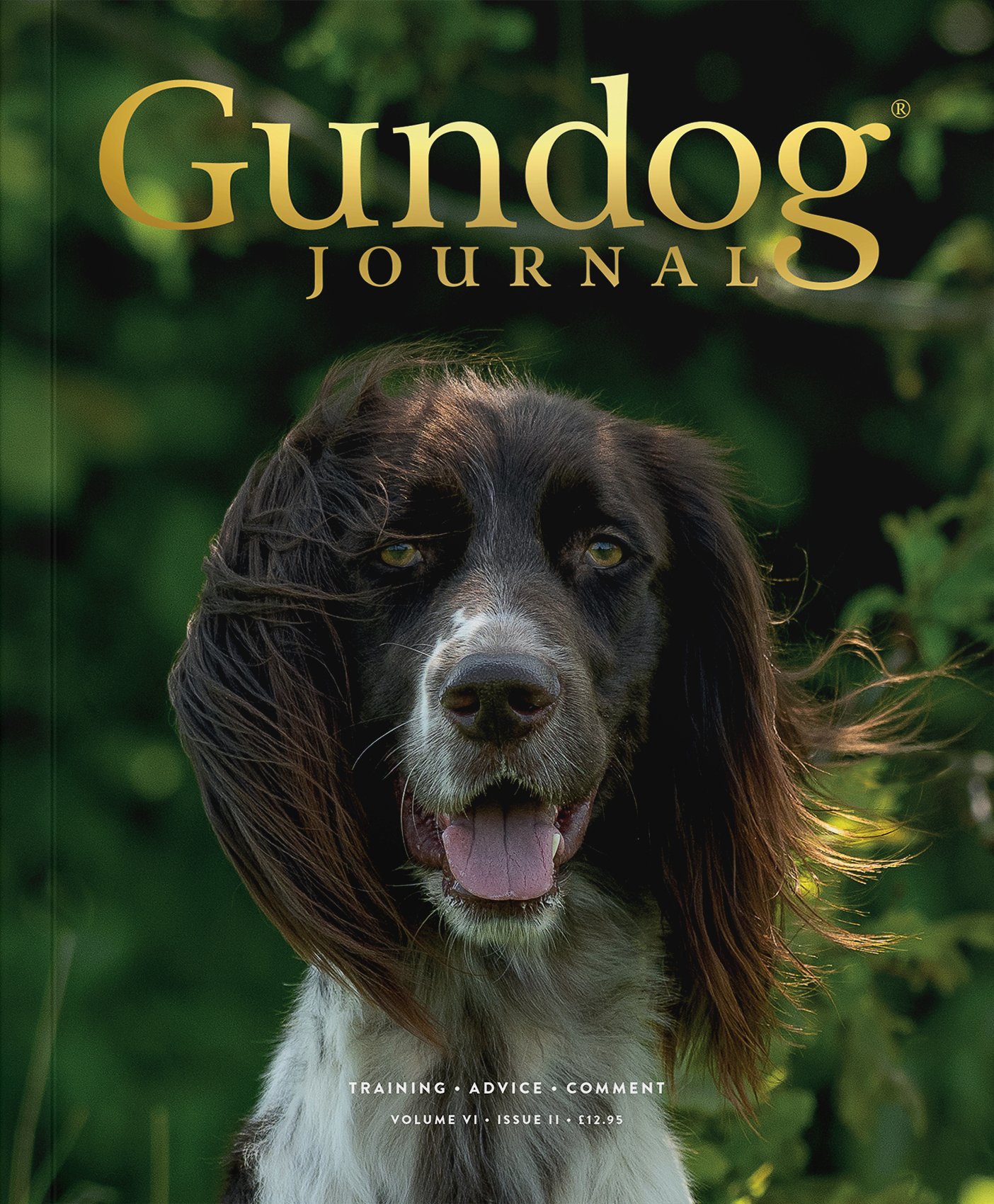

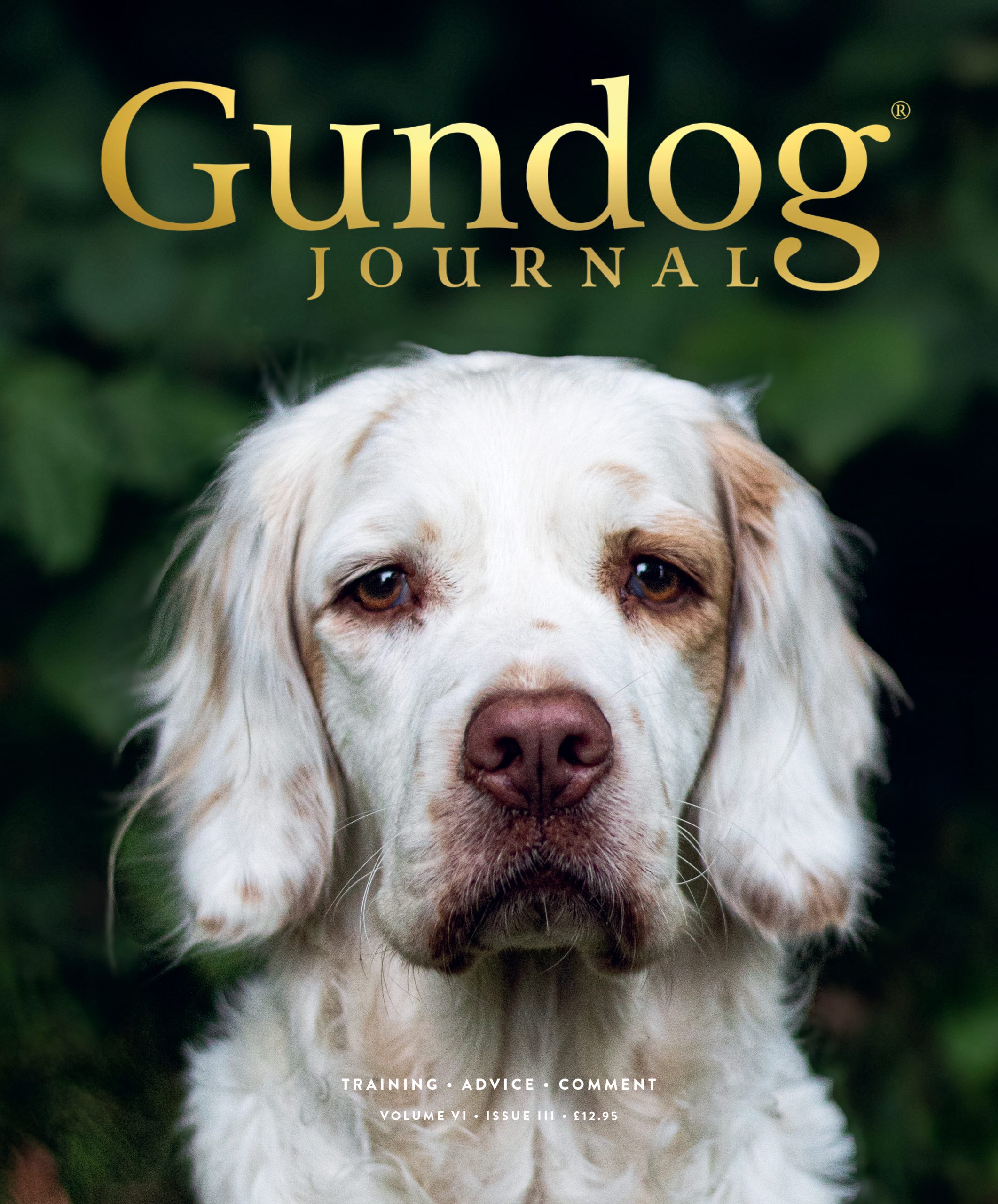

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.