Keeping older dogs listening

For an older dog to continue to pay attention and act on our commands, we must continue to make time for them, too.

“You’ll never have a good young’un as long as you have your good old’un”, George Meldrum used to say. George was twice winner of the Retriever Championship and father of Bill who won it in 1963 handling his father’s FTCh Glenfarg Skid. He had a point. After all, we love our older dogs which have grown into our ways and probably developed a fair few endearing ones of their own.

Provided we think of them as ‘older’ rather than ‘old’ there’s no reason why our relationship shouldn’t be attended by elements of mutual indulgence. Pinning the label ‘old boy’ or ‘old girl’ on our dogs is, after all, the language of affection and the arrival of a new puppy automatically confers honorary senior citizen status on the well established canine members of the household. But I want to use the term ‘older’ rather than ‘old’ because the latter is so often a lazy justification for excusing far too much and for allowing dogs to fit such a description way before their time.

The danger, especially when we have a younger dog coming on, is to give it all the attention and use the old stager in a way that effectively de-skills it: making it a disregarded spectator whilst we work with the young dog, and using it to mop up simple retrieves which we have thrown as a diversion for the young upstart. It is so easily done. We cast the older dog in a secondary supportive role and, in the process, often patronize a perfectly capable companion who will only too readily accommodate your lowered expectations.

Where gundogs are concerned, though, the advantages associated with getting older are surely so obvious they barely need spelling out. Our language is full of expressions which contrast knowledge and that something extra which we recognise as wisdom: and the standard caution about old heads and young shoulders applies just as much to dogs which have to develop a sense of discrimination. As Brigitte Bardot once wistfully mused: “It may be sad to grow old, but it’s nice to ripen.”

The gundog that has ripened is familiar to us all. With admirable experience – and the competence that goes with it – comes a tendency to develop a mind of its own. Extreme versions of this tendency result in the dog which runs itself. But that’s another story. I am concerned for now with the basically steady dog which becomes overly confident. The upside of this, of course, and one we rightly applaud, is the ability to demonstrate real gamefinding ability: the downside, if we acquiesce in its happening, is a progressive decline in responsiveness. We are so pleased, if you like, with the positives that we turn a blind eye to the negatives.

With gundogs, whether or not physical decline is an aspect of getting older, independence of mind almost invariably is. In many circumstances that is wholly beneficial. We set great store by initiative and persistence, but, as so often is the case ‘too much of ought is good for naught’. If independence of mind translates into total self-reliance and disregard of the human part of the partnership, we are nowhere. For, however much we may admire some of the qualities of such dogs, what we are left with is certainly not an agreeable shooting companion.

Let’s try to get to the heart of what I am saying by introducing a word I haven’t used until now: secure. It occurs in an interesting observation by a great conductor about his orchestra and what makes it so special. Although Christophe Von Dohnanyi finds it difficult to describe the ‘Cleveland sound’ he says: “It was always very clear, with a tendency to dryness, and perhaps a little too focused on the beat. I have tried to get them to forget about barlines and become more responsive. If musicians are too secure, they stop listening. The great need is to get them to listen to one another.”

Substitute the word ‘gundogs’ for the word ‘musicians’ in that last sentence but one and you have, I suspect, the nub of the problem with older dogs who have plenty of experience to their credit and are confident that, left alone, they can do the business. In short, they feel secure and are all too inclined to stop listening. The signs of this are apparent enough, even when training with canvas dummies. Instead of marking the fall of a thrown dummy carefully, for instance, the secure older dog may content itself with getting a general fix on the rough direction and range, confident that if it hunts the area for long enough it will succeed. Now that sort of security is often missing in field conditions where birds can plane on considerable distances and complacency is really misplaced. The dog that hunts its way out to a retrieve, refusing to pay any heed to help that might be offered, wastes time and energy and, if walking up, will probably disturb ground as well.

That is why, with older, more experienced dogs especially, periodic refresher courses in basic obedience are a sensible idea. We need, if you like, to listen to each other. Five or ten minutes a day for a few days can work wonders: the whole point being to put brakes on that process of stopping listening. All dogs, especially older ones, are doing it all the time, so never mind that the season is well underway. It’s not something that has to be put off until next spring. When it comes to making sure that the dog/handler relationship stays worthy of the name there is no time like the present.

The world of field trials has furnished some spectacular examples of the way quality, temperament and, above all, responsiveness can be sustained, and even enhanced with advancing years. In retrievers, one thinks immediately of two dogs: both black labradors. Tony Parnell’s FTCh Blackharn Jonty qualified for five successive championships and was still running in the English team in the CLA Game Fair International at the age of ten. More recently the late Mrs Heywood Lonsdale’s FTCh Ulstare Style, campaigned so effectively by John Halsted, qualified for the championship seven years in a row, twice coming second. And he too was anchoring the English team long after most dogs have developed cloth ears.

Same colour and with quality through and through, but at the other extreme of size, was Robin Laud’s cocker FTCh Fenlord Black Beauty who was working right up to her death on August 15, 2004 at the age of 15. A wounded pigeon, shot on the marshes, was brought tenderly to hand with a high delivery: again making the challenging look straightforward, as she had done so often in a career which included six championship runs. A special life which seemed to have no place for pressure.

Such dogs may be splendid exceptions, but they are, by that very token, a beacon of possibility. By taking eternal vigilance seriously even our older dogs can stay sharp. And they’ll thank us for taking the trouble.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

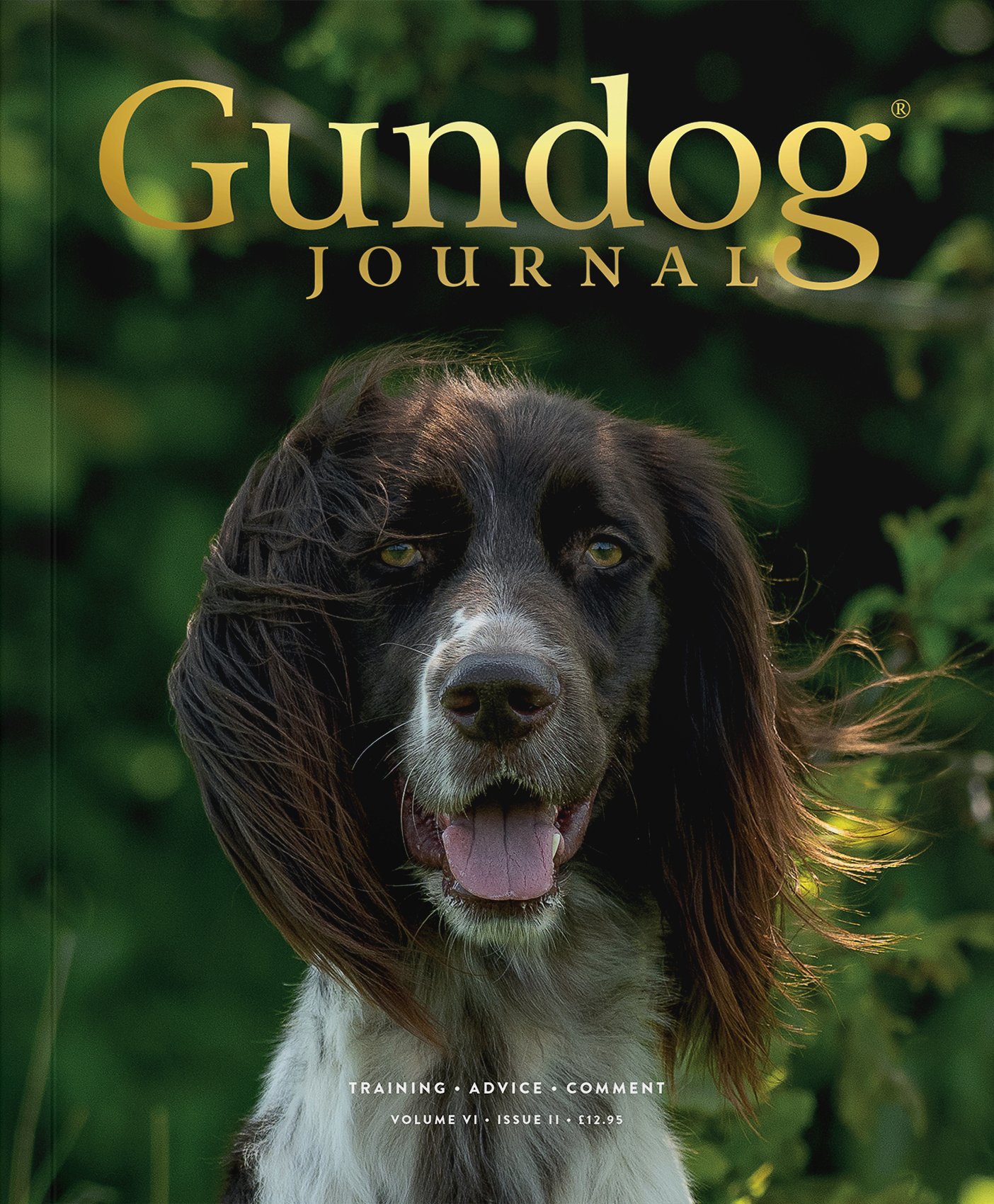

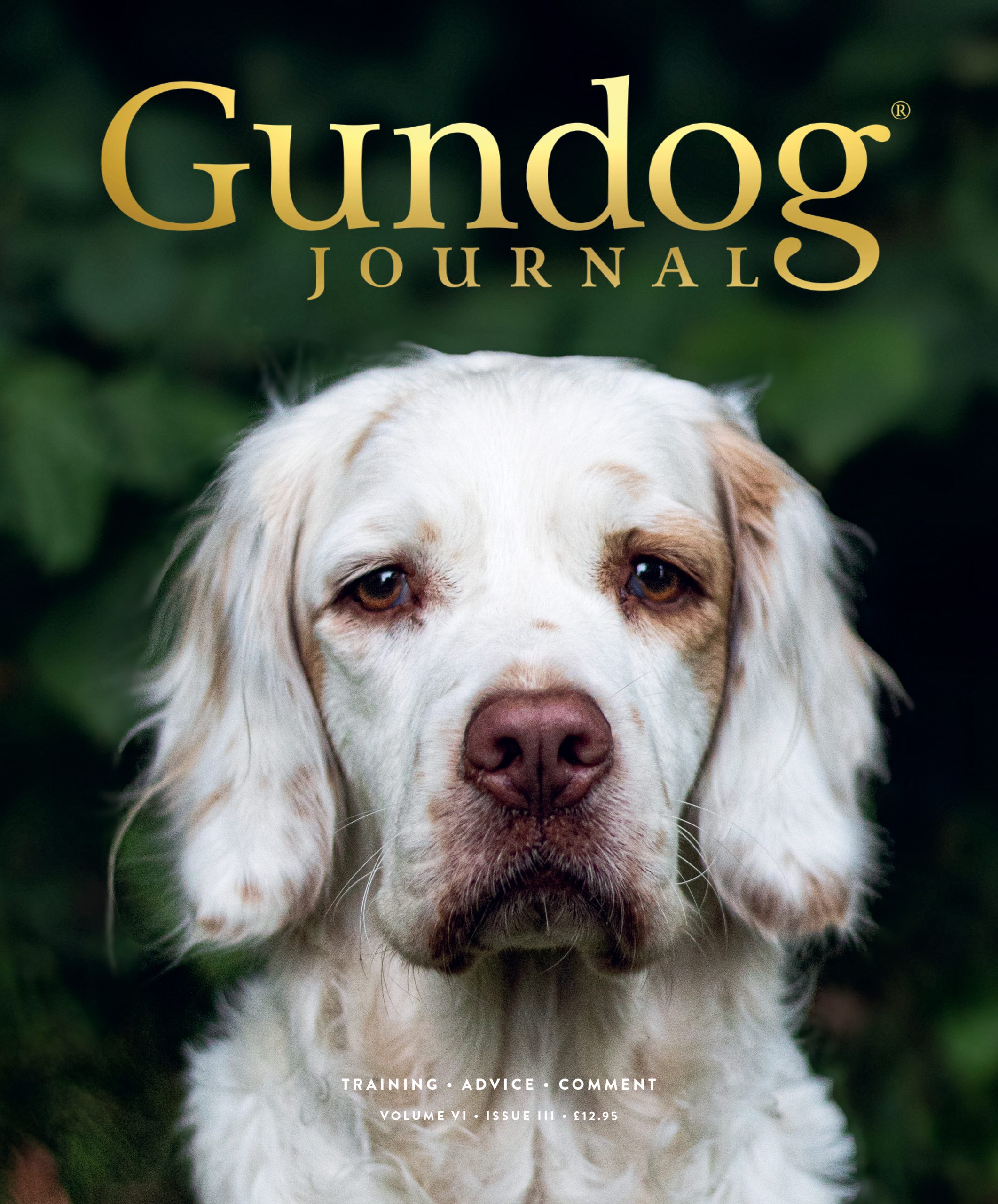

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.