Forever young

How old is too old, and what should we remember when working dogs in their twilight years?

One of the enigmas of life is that as the clock ticks on and our bodies age, our hearts and minds remain ‘forever young’, like in the Bob Dylan song. As I begin the journey of my sixth decade, I often have to remind myself that the voice talking in my head is actually the same age as the rest of me.

This hazy sense of time must resonate even more for gundogs, given their relatively short time on earth. Living eternally in the present, are they aware of the years that pass, of declining senses and bodies that slow down? Or do they require us – the human half of the partnership – to decide when it’s time for them to call it quits?

The most recent Kennel Club health survey shows that the average life expectancy for gundogs is 11 years, with golden retrievers leading the pack at 12 years. But how many years a dog lives and how many of these he can work effectively can vary from individual to individual and across breeds. In his book Gundog Sense and Sensibility, the late Wilson Stephens notes that golden retrievers and cocker spaniels are ‘notably long lasters’. On average, he advises, one can expect about seven useful seasons, after which ‘an old labrador may pick a bird or two (not far from the peg) and the springer may flush a few’, but no longer pull their weight at a normal standard.

I posed this question to Joy Venturi-Rose, a well-known breeder of dual-purpose labradors who also works as a veterinary nurse and teacher. “I think the average age varies for individual breeds. For example, my spaniels tended to live a couple of years more than my labs: labs 12 to 13 and spaniels 12 to 15 years. However, that does not mean they can necessarily work right to the end of their lives. Sometimes they are mentally and physically fit enough but might, for example, be going deaf, which means they cannot hear your whistle and can become a liability. I do have an old lab at the moment who is still able to pick up on a couple of drives and then I change dogs. It is very variable, just like with humans. And it also depends on how fit you keep them during the spring and summer months, how appropriate their diet is, and their general health.”

Gilly Nickols, another successful field trialler who runs Isenhurst shoot in East Sussex with her husband Clive, agrees with Joy about the variability of gundogs’ life expectancy and working years. “That sounds about right – our labradors tend to live for about 11 years. We had one live to 13 but she hadn’t worked for three or four seasons. Older dogs need looking after. Pickups are hard to jump in and out of. There is a danger that they lose fitness through spring and summer, and any injuries will catch up with them as they age.

“Older dogs are more likely to become selectively deaf and stubborn: although they know their job well and have great game-finding experience, they may decide that their owner is all but surplus to the requirements on a shoot day! I have sometimes taken an old dog who would otherwise be retired out at home because it is my shoot. I know I am taking thedog out to make him and me happy and not because he will do anything useful. I usually take him for a drive or two with my team. The ground at home is quite hard with woodland, brambles, thick bracken and lots of water so we need fit and strong dogs both beating and picking-up.”

Joy mentions that along with loss of hearing, failing eyesight for marking birds is another challenge for veterans. “But if they keep fit they often learn to pace themselves and as a handler you need to respect their age and level of fitness and work them accordingly. Expect experience and, wisdom but they might not be able to catch up with some of the fastest runners. If they have been well trained up to the point of old age, they generally make superb and reliable working dogs in later life.”

Sarah Miles, dog trainer and rising star in the field trial circuit, has worked out a system to keep her older dogs involved without asking too much of them. She’s been picking-up at a large shoot in West Sussex for the past 14 years. She usually works eight dogs at a time, made up of her core team of cocker spaniels and labradors, as well as some trialling labradors and one or two youngsters. Once her trialling labradors retire from competitions – which can be at any age – they become full-time picking-up dogs.

With so many ages and job descriptions, she can easily slip in an older dog to sit up for one or two drives before heading back to her vehicle for a much-merited snooze while its team members get on with the job. She notes, “Sometimes an old timer will give me a withering look when sent for a retrieve, as if to say, can’t one of the younger dogs do it?” Joy adds, “Some old dogs get a bit bored with dead game and prefer runners and will start blinking stuff they don’t fancy. Some learn to bring two birds back even though they know they shouldn’t. Actually, older dogs are often so crafty about getting their own way you have to laugh at them.”

Both Sarah and Joy recommend supplements for working dogs from middle years onward to help with the natural deterioration of joints, such as glucosamine chondroitin and salmon oil. Joy also recommends keeping older dogs warm after water work in the winter, although water is helpful because it’s not weight bearing.

As older dogs are losing kidney function they do not always excrete the waste products of protein so easily, so she advises a formulated diet for seniors to provide reduced and easily digestible proteins. “Ensure that you have plenty of water as older dogs can dehydrate more easily and often need more water than younger dogs, again due to their kidneys not being so efficient. Water soluble vitamins such as the B complex also can be lost so these are generally included at higher levels in a senior diet.”

Sooner or later, under our watchful care, the inevitable day arrives when retirement beckons. I ask my gundog experts how they know. Gilly replies: “Before they become a nuisance rather than a pleasure on a shoot day.” Joy gives a list of symptoms: “Can’t hear the whistle, unreasonably stiff the next day or the dog telling you it would rather stay at home in the warm.”

The next step for Gilly is usually finding a new home. “I don’t keep many of my dogs to old age. When I have had the best of them from a training and competitive view point I will either sell them as a peg or picking-up dog or rehome them as sofa dogs.”

Sarah knows her dogs are approaching retirement when they start slowing down, usually at 9 or 10 years, and don’t want to pick up anymore. At this point, some of her dogs are moved from the outdoor kennels to the house. There are exceptions, though: one elderly labrador agreed to come to the house in the evenings but preferred to go back to her kennel to sleep.

Like Gilly, Sarah works her dogs hard, often three or four times a week during the season. Many of her dogs are rehomed, to what she calls their ‘forever homes’. “It’s surprising how many people, like elderly couples, prefer to take on a trained dog with a proven temperament rather than a puppy. They become very spoiled, with a life in front of the fire, cuddles, tidbits, easy walks,” she says. “They’ve worked hard for me and I’m happy to provide these comforts for them in their old age.”

One of these dogs, her cocker Lulu, stopped working at 11 and was sent to her ‘forever home’ with Sarah’s recently widowed mother. Now 16, Lulu is thoroughly spoiled and happily looking after Sarah’s mum, who’s in her 90s.

If our gundogs, with their instinctive high drive and brilliant working abilities, can so easily adapt to a life in front of the fire when the time comes, I guess they do understand a thing or two about ageing. It all comes down to a sensible reciprocal partnership and being attentive to your dog’s needs. After all, as Wilson Stephens points out, each dog represents a decade of our lives, no matter how many dogs we own. And the decades pass quickly.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

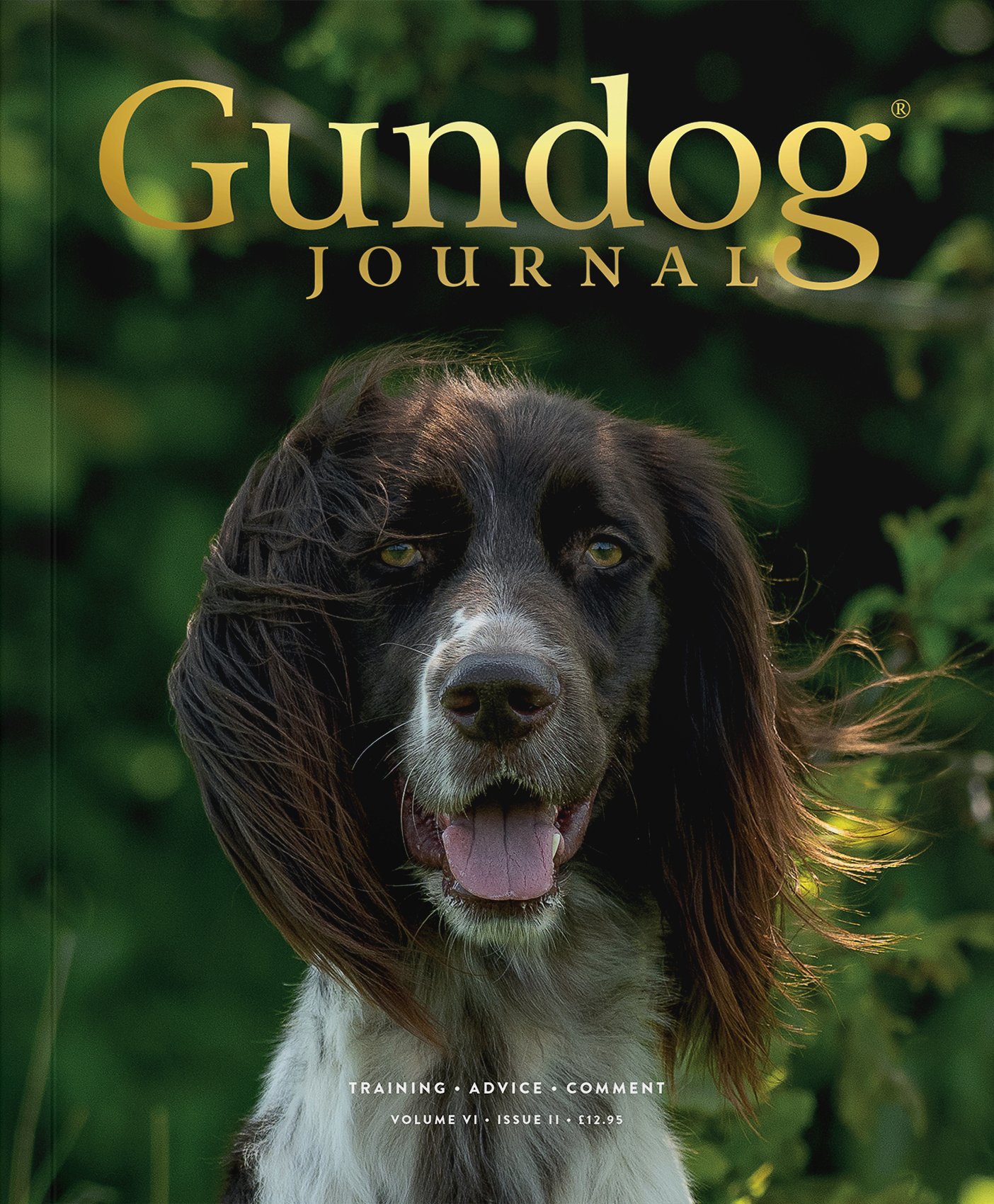

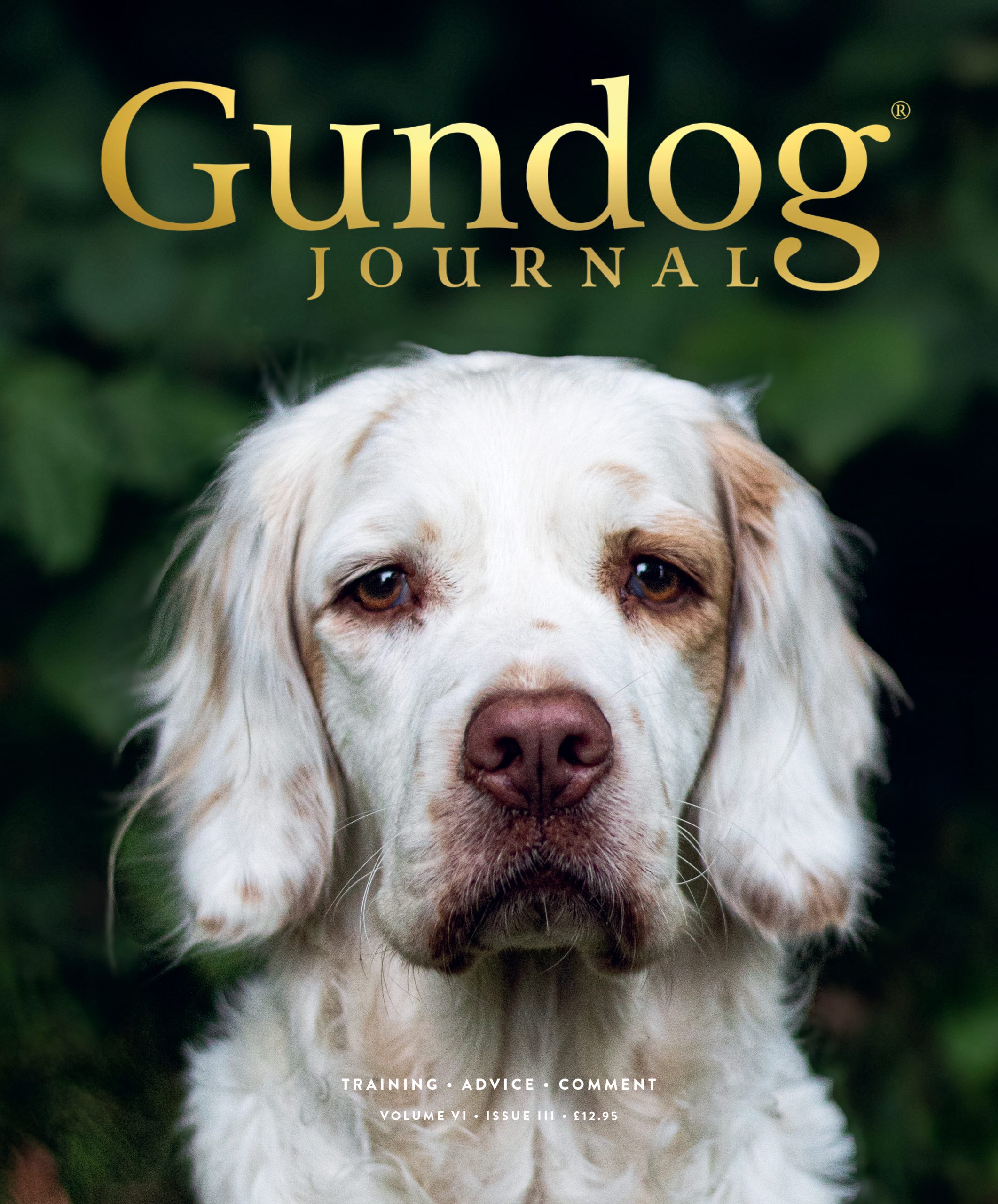

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.