Training

Back from the brink

They might have patchy backgrounds, but with the right approach rescue gundogs can make excellent working partners.

Would you like to appear on our site? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our readers. Find out more.

Scientists have long puzzled over how man’s best friend came to be. Even today, unanswered questions surround the evolution of our domesticated dogs. What we can say with confidence, though, is that thousands of years ago canids and humans began hunting in one another’s company.

Our bond with dogs has grown immeasurably since, and those early canids have evolved. The millennia have worked in our favour; recognised breeds now have niches for which they have been shaped and sculpted over time – a will to work is hard-wired in their very nature.

Today, however, dogs are rapidly having to adapt to our changing lifestyles. Of course, their ability to do so in the past has been fundamental to their domestication, but problems can and do arise when ingrained instincts are not in some way catered for. The gundog breeds are no exception. And nobody knows this more than Lincolnshire-based dog trainer Jonathan Roberts.

On the coldest day of the season, I joined Jonathan for the morning on one of several shoots where he racks up 60-70 days picking-up each winter. It was a standard day for him, but a curious one for me; each of the dogs which shuffled excitedly in the cab behind us sat on an engrossing story – patchy backgrounds, peppered with problems.

Our destination was the back edge of a wood in Stubton, south Lincolnshire. It was the last week of January. Parked and in position as the distant calls of beaters preluded the first shots of the day, a black labrador by the name of Shadow sat patiently at Jonathan’s heels. Her story and that of several of her kennel mates unfolded as the drive progressed.

Shadow was Jonathan’s first ‘rescue’ dog, collected from a labrador rescue group which fosters dogs before finding them homes, usually as family pets. “With all her energy and drive, Shadow had become a bit of a handful,” Jonathan explained. “Her previous owners simply hadn’t exercised her enough. And without that stimulation, young dogs in particular grow bored and develop undesirable behavioural traits. Working breeds are simply not suited to sedentary lifestyles.”

Yet despite her rough start to life, here Shadow was, seven years later, marking birds with aplomb, serving a purpose, and more alive than ever. Her plight was brought to Jonathan’s attention by one of several rescue centres that stay in touch. “If the centres are at capacity and a dog is unlikely to find a home, or a recent rehoming effort has failed because of a problem like aggression, I will often get a call,” said Jonathan. “If I am in a position to help, I will take the dog in for assessment. Just like any that come in for training, all dogs are assessed on individual merit. Obviously, with rescues there is often a lot of uncertainty surrounding their backgrounds, so it does take more time.”

Quite remarkably, Jonathan has recruited a number of rescue dogs to his picking-up team over the years. And his success in doing so is in no small part down to his training approach. “The first thing I do is allow at least six weeks for a dog to fully settle in and get to know me,” he continued. During this time he will watch a dog carefully to identify any habits and triggers for certain behaviour, whilst focussing on building trust. Then, when he feels the dog is ready, basic training will start. “A common mistake is to rush the process,” he added as Shadow delivered a hen bird neatly to hand. “People are so eager to try and make dogs like them, which can be overbearing and make things worse. A lot of rescue dogs are very nervous and insecure, so I always let them come to me in their own time.”

Of course, not all of the rescue dogs that find their way to Jonathan are suitable as gundogs, and that’s fine – he rehomes a number of them with suitable owners – but many do show some ability which can be nurtured and built upon. Testament to that were the three characters back in the truck, eagerly awaiting their turn to help pick the day’s bag. Anyone who has trained a gundog will be familiar with the challenges that can crop up; those which are overcome with the help of a solid foundation established early on, a toolkit of sound training principles and a good pinch of flexibility. But Jonathan’s rescued recruits rarely have the former, so it’s down to his experience and knowledge, and perhaps more than just a pinch of flexibility, to prepare them for the shooting field.

Right from the start, positivity is key. “When training a rescue dog, everything you do must be positive, and they must associate you, and being trained, with good things,” he went on. “If you’re not in the right frame of mind, don’t even bother; you won’t achieve anything and can undo a lot of good work through negativity.”

By this point, Jonathan had fetched another of the dogs from the truck. Scout, an 18-month-old black cocker, was there to watch the more experienced Shadow, learn a little, and practise patience. He had come to Jonathan the day before he was due to be euthanised for biting his owner. “The first thing I did was change his name, which was originally Sam, to something else,” Jonathan noted. “It was clear that there had been a lot of negativity in his life, and I didn’t want him to associate his name with that negativity.”

As we finished sweeping the area of young trees in front of us, Jonathan outlined the fundamentals of his approach. “There must be trust, expectations must be realistic, and it’s vital to be honest with ourselves about a dog’s capabilities,” he admitted. “My rescues aren’t and never will be perfect gundogs. But I can find jobs for them, especially when picking-up, and they love it. They may not be rock steady on a peg, but they make up for that behind the line with enthusiasm and game-finding ability.

“Like any dog, they have their off days and can switch off if nagged. If they are doing something wrong, I’ll put them on the lead and they’ll quietly be taken back to the truck. Problems can be ironed out in the training paddock – there’s little point in shouting and screaming at a dog; nobody wants to see that.” He was quick to point out that if he and his dogs were not effective, they wouldn’t be invited back. After all, a commercial shoot relies on a good team of pickers-up.

The second drive saw Shadow substituted for two of her younger team mates – Neo, a four-year-old springer, and Chester (3) a Jack Russell. Like Shadow, both started life very differently to most working dogs – Chester in particular developed a range of issues including aggression towards other dogs. Neo was found stray and roaming a Skegness beach. And even after his original owners were traced, he remained homeless until Jonathan took him in.

Birds were soon on the wing, zipping over the Guns. Neo watched eagerly as, ahead, partridges and the odd pheasant fell or pitched into cover behind the line. Chester, not so apt at marking, would instead rely on low ground clearance, a terrific little nose and a surprising retrieving ability for a terrier.

With the drive over, both were soon set to the task, Jonathan keen for them to do their own thing. “I like a dog to use its initiative and get on with the job when pickingup. At the end of a drive, you generally don’t have time to direct them onto each and every bird. And often you might not have seen a bird fall. Trusting your dogs and having confidence in them is important. And it makes it so much more enjoyable.” Indeed, the enjoyment for both parties, despite the bitter weather, was plain to see. We were a world away from their troubled pasts.

further north

Carol Begg established Perthshire Gundog Rescue (PGR) in 2009 in an effort to help those struggling with their dogs, offering support wherever possible to give people the chance to overcome any issues affecting their ability to keep dogs.

“Our work at Perthshire Gundog Rescue involves more than rescuing and rehoming gundogs, though,” Carol is quick to point out. “Last year we rehomed 22 dogs – dogs of all ages, from five weeks old to 15 years old – but helped over 200 people keep their dogs, too.”

This ‘help’ is broad in nature and ranges from working with individuals to improve their understanding of training and the requirements of different dog breeds, to a dog food bank for those who have fallen on hard times and even a 24-hour helpline which people can call for support and advice.

“We work with many people who are struggling to keep their dogs because they are suffering from financial hardship or mental health problems such as depression and anxiety – issues which can lead to them doubting their ability to keep their dogs,” says Carol. “Many people are invited to HQ so we can work with them on a one-to-one basis. We also work with other professional bodies where we can refer people for help if necessary. I am proud to say that the work we do has not only saved many dogs’ lives but has saved the lives of dog owners, too.”

Has Carol noticed any particular trends during her decade running PGR? “Spaniels, particularly cockers, are the breed we see most frequently,” she observes, matter-of-factly. “And this is often because the owners have not taken the time to research the breed, its requirements and traits.”

Carol encourages prospective gundog owners to spend time with professional people who own at least a few generations of the breed they are considering. “This allows them to get to know any breed traits,” she claims. “It’s also very useful to know somebody who can offer advice on how to deal with any breed specific issues.

“Dogs, like people, all have their own personalities – they’re individuals. When I rehome a dog I always ensure owner and dog are a perfect match. Different dogs have different needs, it’s important to remember this.”

And yes, many of the dogs Carol does find new homes for go on to work eventually. “If I get a dog in that I think will make a working gundog, it is put through its paces and the perfect working home is found. That might be a gamekeeper, or a keen Shot who works the family pet on a dozen days a season.

“That said, while I like to get as many dogs into working homes – and we have had many “failed” gundogs go on to new working homes and shine in the field – it’s not a top priority. I’d rather a dog have a great pet home rather than a bad working home, and vice versa. The dogs dictate to me what’s best for them…”

Related articles

Training

Patience is a virtue

It’s a skill that is often overlooked in training, but which is vital for all gundogs. Ben Randall explains how to capitalise on some everyday opportunities to practice it, now that spring is here.

By Time Well Spent

Training

The theory of puppy training

When you collect your puppy – and at every stage thereafter – you’ll need a safe and secure form of transportation. Here are four high-quality options to suit all requirements.

By Time Well Spent

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

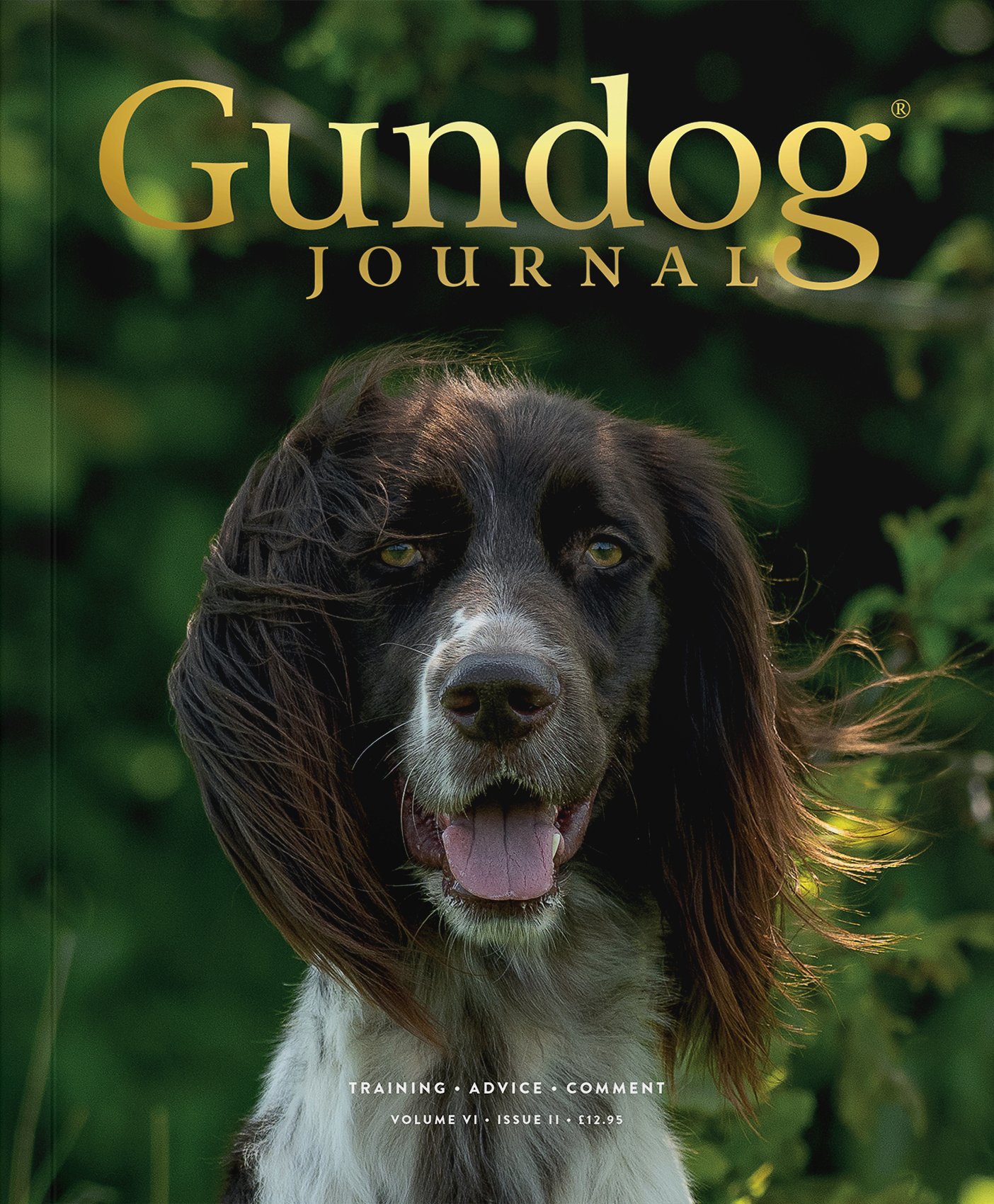

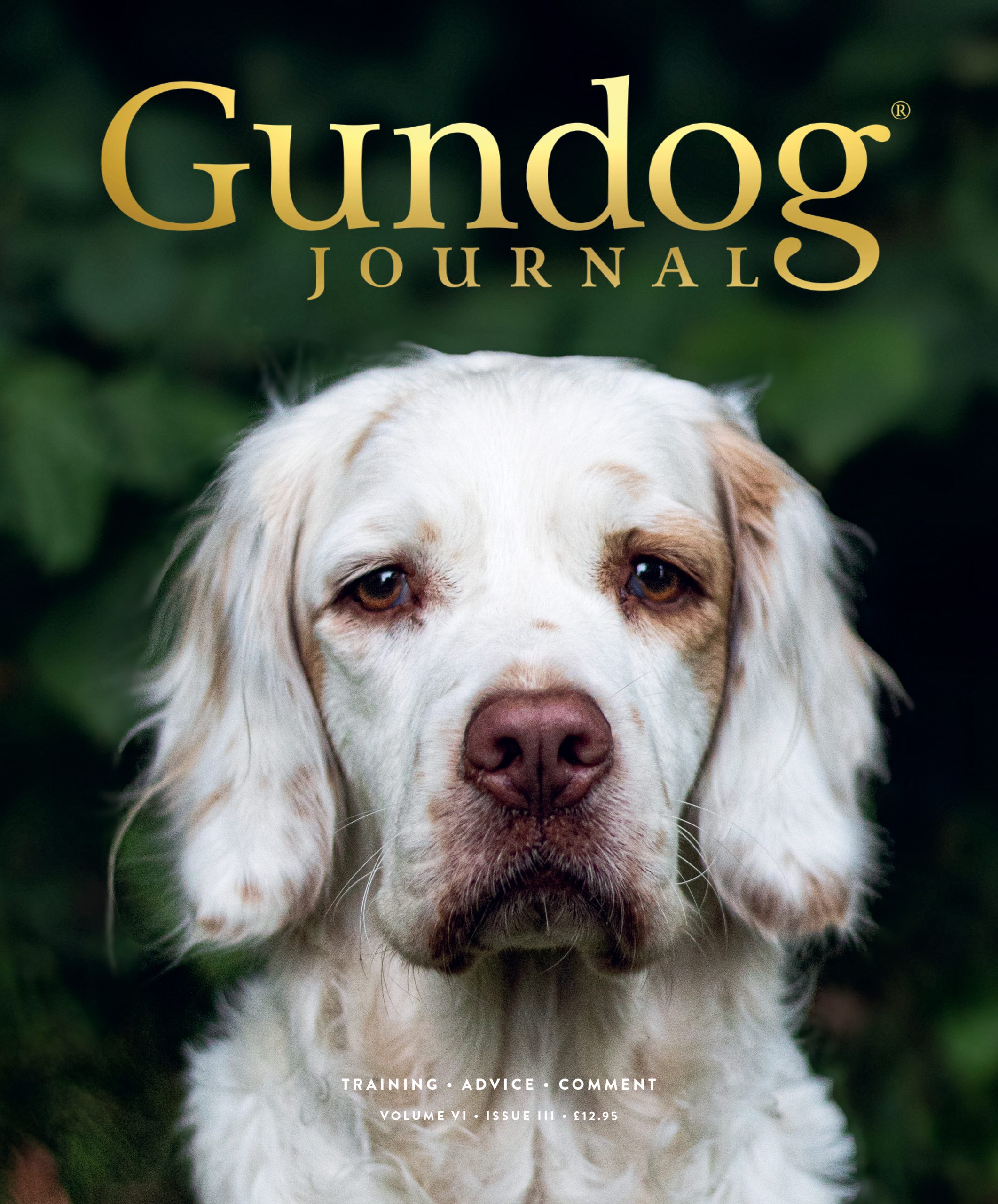

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

Whether you’re a professional handler, breeder, or simply passionate about gundogs, each issue offers a wealth of knowledge on breeds like labradors, spaniels and vizslas. Subscribers gain access to topical articles, real-life stories and exclusive offers from trusted brands.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating these remarkable working breeds.

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.