Ugly vanity

The show ring has had a ruinous effect on many of our working breeds; an array of conditions now affect hundreds of thousands of dogs across the country. But, thankfully, there are those who are battling to protect the treasured bloodlines under threat.

In October 2015, the working Jack Russell terrier was condemned to a long and drawn out death. The Kennel Club had announced the charming scallywag as the latest to be recognised as a terrier breed in the UK, joining 26 others under the pedigree banner. But did New Year’s Day 2016, the date of registration, mark the start of a long and pitiful decline for yet another of our most treasured working breeds?

Nothing spoils dogs like shows; useful breeds, registered as pedigree and then exploited for status and money. Aesthetics take precedence over function, and working ability is the loser, time and time again.

The proof lies in the past – the history of the show ring is as undeniable as it is grotesque. How many cairn, Welsh or West Highland white terriers have you seen going to ground to flush a vixen? Instead, they clog up veterinary surgeries with their skin problems. Or eye problems. Or jaw abnormalities. Or increased susceptibility to disease and seizure.

Make no mistake, this myriad of hereditary defects is a result of inbreeding in an effort to meet specified ‘breed standards’ (a picture in words that describes each breed of pedigree dog). The same noxious standards that caused the BBC to pull its coverage of national dog show Crufts in 2009 – the first time in 40 years the event had gone untelevised.

The show ring has had a ruinous effect on many of our working breeds; an array of conditions now affect hundreds of thousands of dogs across the country. But, thankfully, there are those who are battling to protect the treasured bloodlines under threat.

A century ago, if a gundog was unable to perform the duty for which it was bred, its line would be discontinued. Today, where dogs are valued for their looks rather than their ability to work, the bitch with skewed hips is bred from. Imagine the outcry if the hunting community were breeding hounds unable to give birth naturally, or field trial champion spaniels were crippled and unable to walk beyond their third birthday…

Crufts, an evolution of the Gamekeepers Association AGM in 1901, was once a focal point of the keeper’s year. Indeed, the Gamekeepers’ Ring is the oldest in the show’s history – a place where keepers and their wives would convene at the end of the season. Judges with an understanding of working breeds would judge dogs that had recently finished a season in the beating line or picking-up team. Conformation was important, but no more so than physical soundness and the ability to hunt, flush and retrieve game. BASC have helped to keep this (now minor) part of the show alive, but the heart of the main show ring schedule is synonymous with judges who know little about the working capacity of the breeds they judge. Our forebears would wince.

Since 2009, the Kennel Club has reviewed breed standards across the board in an effort to “make it explicitly clear that the process of exaggerating features because they are seen to look good, when at the expense of the dog’s health, is not in any way acceptable”. Time will tell if these words carry any weight. Regardless, that a dog bred for the show ring will, by and large, be unsuitable for proper work is inescapable. Rats, rabbits and pheasants care little for how a dog looks. It is courage, nose, athleticism and intelligence that make the difference in the field.

Despite descending from the same foundation stock and sharing the same Kennel Club breed standards, on the whole, show and working dogs of the same breed are now distinctly divided. As a consequence, the size of the gene pool for both ‘types’ has decreased considerably – hence the increasing trend for owners to calculate the Coefficient of Inbreeding (COI). Simply put, COI is the probability that two copies of the same gene have been inherited from an ancestor common to both the sire and dam, and COI calculations can be used to aid informed decisions when choosing a breeding pair. That they are required is lamentable.

To put things into perspective, you need only look at Estimated Effective Population Size (EEPS) figures – a measure of the size of a gene pool in a breed. Recent values, calculated by using the rate of inbreeding between 1980–2014, for cocker spaniels, labradors, and Irish setters, are 49.1, 81.7, and 27.3, respectively. Figures lower than 100 are considered critical by conservation biologists. Those below 50 indicate a breed at grave risk.

CAUSE FOR OPTIMISM

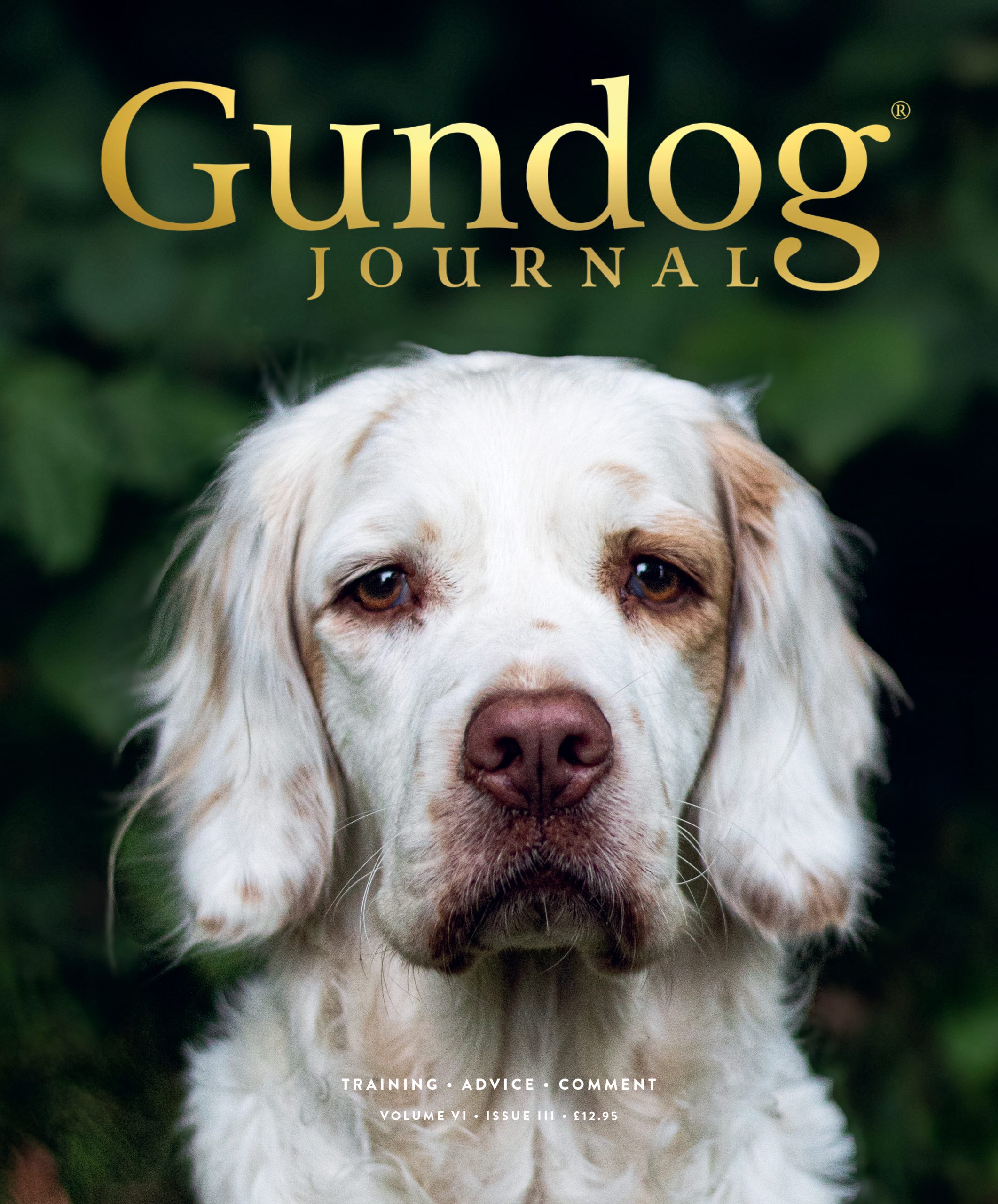

Thankfully, there are those who are battling to protect the bloodlines of our working types. And others still who strive to restore those breeds all but depleted of their working qualities. In this respect, the Working Clumber Spaniel Society (WCSS) is exemplary.

Founded in 1984 by James Darley and a group of likeminded enthusiasts, the WCSS set out as a means of giving a collective voice to those interested in the breed other than as an ornament, with its health and working characteristics in decline. In the 35 years since, the Society has grown in numbers, stature and influence. The WCSS labours to maintain a considered breeding programme in which members participate with a conscious common goal – to rebuild the type of Clumber so successful in the field in the past. Selective breeding from working stock is key. So too are passionate and dedicated people.

Under this ambitious and innovative scheme, dogs are assessed for natural working ability, limited weight, hip dysplasia, and freedom from entropion (rolling of eyelids), in order to establish their fitness for purpose.

But as Clumbers have survived solely as a consequence of the show ring – with insufficient support from sportsmen in years gone by to ensure maintenance of working qualities, soundness and trainability at high levels – just how much can be expected of them?

So far, signs have been extremely positive. In the 21 shooting seasons since ’97/98, 21 different Clumbers have won field trials – an impressive statistic considering there was only one winner in the 87 preceding years. Arguably the most notable success was in early 2017 when Midori Diamond Huddlestone (Rigg) won an AV spaniel novice stake, competing against 15 springers.

What’s more, hip scores are now mostly in single figures or the low teens. The average hip score back in 1998 was 44! The WCSS continues to outgrow the breed club, and through generating awareness and educating the sporting and general public about the health issues affecting the breed, the society has effectively shaped the demand for it.

I was able to learn more when I joined a group of enthusiastic Clumber handlers on a training day hosted by John and Debbie Zurick at their home on the edge of Exmoor. T

o say the Zuricks are dedicated to the cause of developing our largest native spaniel breed would be a disservice. In addition to kennels full of them, Clumbers adorn canvases and even coffee coasters inside Nethercote Cottage. Perhaps it’s something about rare breeds – they have kept Gloucester old spot pigs and Dexter cattle in the past.

Debbie has owned Clumbers for 23 years, and been secretary of the Society for 21. She previously had springers, and John, labradors, until the arrival of their first Clumber. Ever since, they have endeavoured to resurrect the breed as a working gundog. They pick-up regularly throughout the season with their team at shoots including North Molton, Edgcott and Great Bradley.

I joined them on a rough, walked-up day in copybook spaniel country – think bracken, rushes, bramble and gorse. The emphasis was on training the dogs, all seven tasked with heelwork, hunting and retrieving. We numbered 10 including Clumber-mad photographer Heidrun Humphries, five of us shooting. Three cars made a combined round trip of over 1,000 miles to attend. This sort of commitment is intrinsic to the WCSS’s success.

Preconceptions of ignorant, soft-eyed, heavy-set plodders soon dissipated. Three decades of thoughtful breeding has produced a spaniel now with largely excellent eyes, hips and trainability.

Clumber spaniels offer one thing more generously than many other gundog breeds, and that is time – a rare gift, nowadays. Granted, they don’t work cover quite like a springer, but their deliberate and slower pace also means they are less likely to run over game. They were a real joy to walk behind, offering the chance to enjoy the surroundings. No rushing. “We wanted a dog that we weren’t raving to keep up with all the time,” said John, “A slower spaniel that worked at a steadier pace, whether it be 9am or 3pm, that was good at retrieving and would sleep in front of the fire.” I think they’ve succeeded.

Society Chairman of seven years Andy Hales likens them to where cockers were 20 years ago. “Clumbers take longer to mature than cockers,” said Andy. “But their trainability has improved markedly. What’s more, people now see a Clumber on a shoot day and know what it is.”

So the WCSS seem to be leading the way by carefully restoring a valuable working gundog from the ruinous effects imposed by a show-driven breed standard. Nowadays, increasingly, there is some meeting of minds between the breed club and WCSS, at least offering hope for future co-operation between the two.

Perhaps, then, there is hope for our working breeds yet. John Smith-Bodden, the editor of the Society’s annual publication, sums up the state of affairs fittingly: “Like a dog hunting a downwind, we might be pulling on,” he writes, “but in our case that’s not a bad thing – we’ve a lot of ground to cover…”

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.