The worst of times

It’s the most difficult of subjects but here Tom Jones faces up to the sad reality of losing a beloved gundog and realises just how much they give us

I’ve written a few fieldsports articles over the years. Writing them, it must be said, isn’t the most arduous or difficult task in the world – in fact, it’s quite a pleasant experience. It usually takes a couple of long evenings, a few bad jokes and a good glass of something strong. In fact, the opportunity to revisit a perfect day out ‘when everything that is good rejoices’ makes it a bloody marvelous pastime, frankly.

This article, on the other hand, has been an absolute bugger to write. I struggled with it almost as soon as I started it and after a few hours staring at the few words I’d come up with on my screen, I decided the best thing to do would be to put it off. And keep it off. In the month or so after this article was commissioned, I’ve been to the pub more times than George Best and I’ve drunk enough to float the Home Fleet. I started watching Mad Men again, and I’m already four seasons in. I even joined a gym.

The moment of catharsis

Why? I suppose I probably put it off because this article is my moment of catharsis. Earlier this year I lost my working labrador, Jim, to a sudden illness that took him in a day. That is what set me to writing this article, because it has made me realise that the loss of a gundog, whether of the beating or peg variety, is not like losing a pet. The experience I went through – that we have all been though – is different from losing a pet. Losing a pet is just that – losing a pet. That’s hard enough, but our experience is something deeper.

So why in Heaven (before we are there)

Should we give our hearts to a dog to tear?

So wrote Kipling. In classic Kipling style, he cuts straight to the heart of something that defines us. Losing a pet makes us wonder why on earth we have the bloody things in the first place – we give our emotions to these animals when we know they’ll hurt us. And yet, we carry on, loving without counting the cost. If it’s a calculated risk, then how are we all so bad at maths? Why do we do it?

DOGS KEEP US GROUNDED

Perhaps what we seek from them is a sense of place – dogs tie us down wonderfully. It was only when my home suffered a sudden absence of dog that I realised Jim had made it his life’s work to anchor our house down. I had thought he was being lazy. Sleeping in front of the fire, not rising until at least after 9am, occasionally working himself up to examine me with urbane disinterest from across the room. I see now it was all a clever ruse. I see now that the look or urbane disinterest was a love song in a language I never understood. I see now that he was using all four paws and that great, thwacking tail that seemed to pound every surface he encountered like a propeller to keep us in place. Without his hulking, heavy, hefty love, our home has lost all sense of foundation. It slides and shifts, the slightest gust turning it on its edge. Losing a pet is not just losing a sibling, a son, a daughter. Losing a pet is proof that man is not made for himself alone.

GUNDOGS ARE THE TALENT

But losing a gundog is different. Why? I believe it’s because our dogs aren’t just pets – our relationship with dogs is different. And it follows, then, that our experience of loss is different. When people lose a pet, they lose a being that was totally theirs – a dependable dependent, if you will. But by working our dogs, we see a different side to them. We take them to the heather or the field, we give them a rough idea of where the birds are, and we hand over to them. They are the talent, and to try and tell them how to use their talent is bringing owls to Athens. Once you have worked a dog, you are no longer solely, wholly, their master. You have become colleagues – you are their manager, perhaps, but not their master.

This is certainly my experience. When he got into the field and after grouse, Jim became almost Bedlam-mad. He had that instinctive knowledge of what he was doing which comes pre-installed in all gundogs. It’s the result of generations of people just like us putting in the same time and effort we did to train the generations of dogs that came before ours. As he bounded through the heather, crashing and bellowing like a stag herd, his single-mindedness was something to behold; once he was over, under and threading through those tiny purple flowers he had so little respect for authority figures I suspected that Che Guevara might have had a picture of him on the wall of his Buenos Aires student flat. We soon formed a working agreement – I grew to understand, over the years of working him, that direction from me was ill-used and seldom sought. So I stopped giving him any.

THE ESSENTIAL FUNCTION

That pure purpose is often how you’re able to tell a good gundog from a great one. The natural instinct can only be harnessed, not trained, and when we see it, we can’t help but marvel. The purpose, in fact, has a handy name – it is what Aristotle called ‘entelechy’. Encylopedia Britannica defines it as ‘that which realises or makes actual what is otherwise merely potential.’ The Greek spent many years studying the difference between what something is made of, and what makes it what it is. Entelechy, he decided, is what distinguishes something living, something with a purpose, from the simple matter that makes it up. It is the essential function of being. For us, and our dogs, that is working in perfect concert.

That, I believe, is why we find watching dogs working such a captivating example of sublimity and why these animals give us cause for such deep joy. We are watching an animal fulfil its entelechy, and our role in that means we experience something few other pet owners ever encounter. This is the formation of a relationship based not on dependence, but on co-dependence, symbiosis, harmony – call it what you will.

But the existence of this unique bond means that when we lose a gundog, each one of us becomes the captain of a boat with no oars. We lose a partner, a true part of ourselves, and part of our own entelechy too. We form such a strong relationship with these animals, and fall so heartbreakingly in love with them, that they become part of our reason for being.

But to go on extolling his virtues further would be gilding the lily. The last word, I shall give to a man inestimably more wise than I. The Pope, recently, was asked if dogs went to heaven. His reply was simple: “How can heaven exist without dogs?”

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

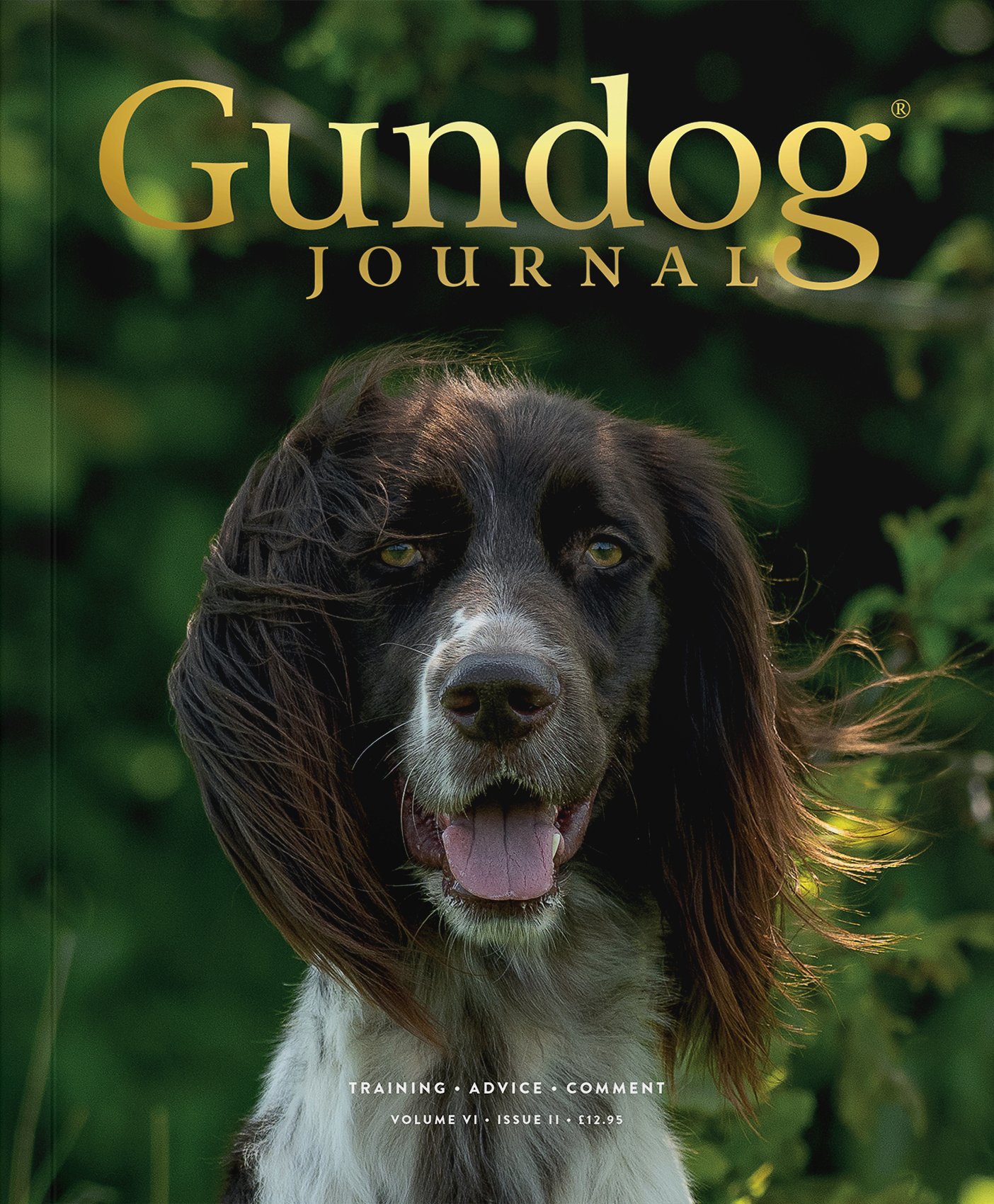

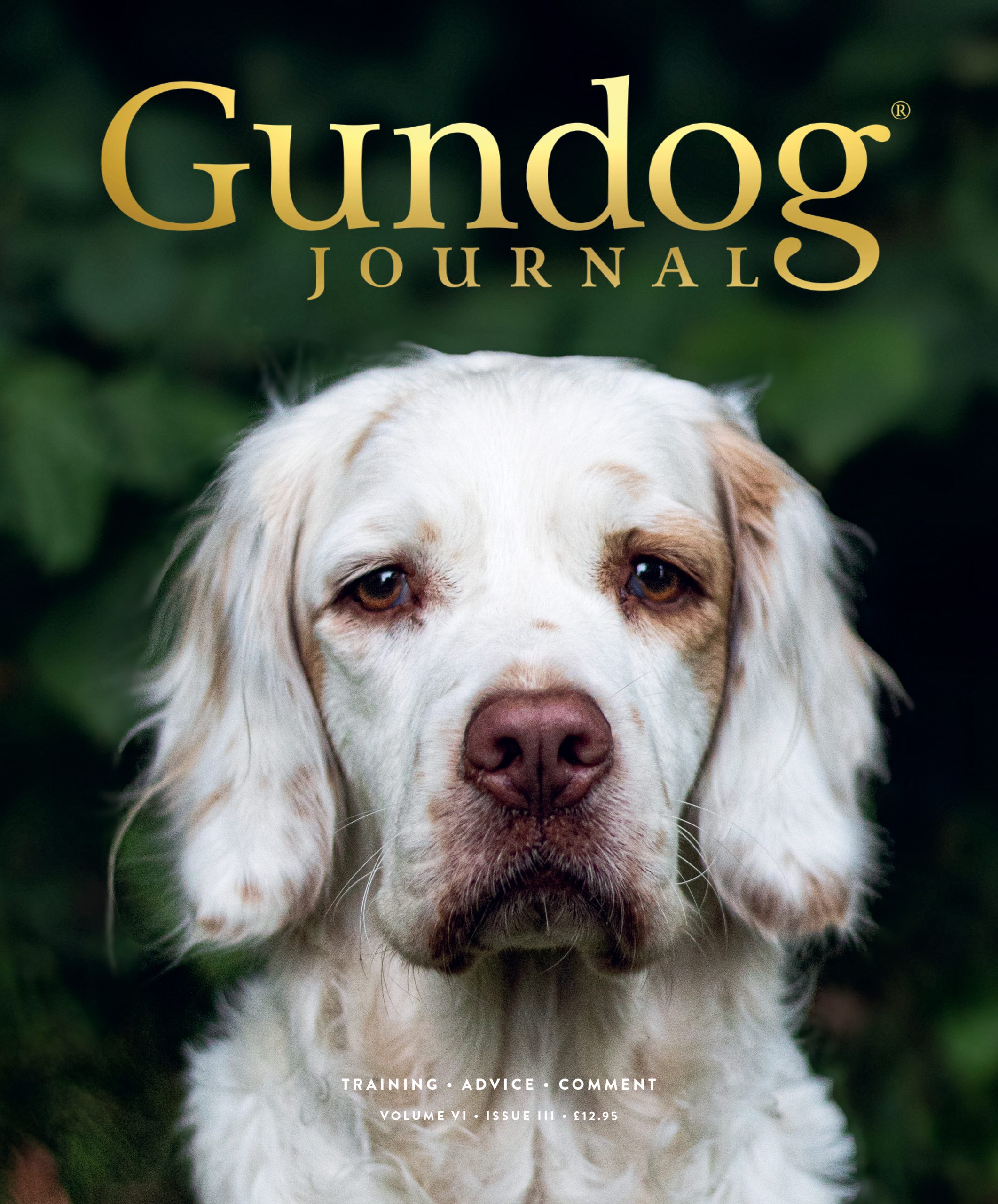

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.