★ Subscribe to the Gundog Journal newsletter here for first access to competitions, breaking news and exclusive content ★

The Trouble with Ticks

The continual threat posed by ticks and Lyme’s disease means constant vigilance is vital for gundog owners, as Laura Keyser explains.

Ask people what they associate with ticks and they will probably say bracken, summer weather and deer. However, with climate change and European pet travel on the increase, there is so much more to these arachnids than people think, and they are an ever-increasing risk to both dogs and humans alike. This means dog owners need to be more aware than ever and at all times of the year – particularly the increasingly warmer autumn months of September, October, and even November…

Part of the spider family, ticks are found worldwide and there are more than 20 species in the UK, the most common being Ixodes Ricinis (the sheep tick) and Ixodes Hexagonus (the hedgehog tick). Ticks are blood suckers and have four life stages; eggs, the six-legged larvae, the eight-legged nymphs and adults. Once hatched, each stage requires a blood meal to develop and reproduce, and that blood meal may well come from us or our dogs.

In search of a host

Ticks seek out their host by ‘questing’, or crawling up vegetation, often in dense wooded areas and on moorland, exactly where we are working our dogs, until they can attach to a passing host. Once attached, they secrete a cement-like substance produced by the salivary gland, which literally glues them in place while they feed. After 24-48 hours, they can start transmitting diseases to their hosts.

Ticks used to be predominantly seen in spring and summer but with warmer winters and wetter summers, they can be seen all year round and are active for longer periods. The main tick-borne disease in the UK is Lyme’s disease, caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi, which affects humans and dogs alike.

And with more relaxed pet travel legislation, it is no longer compulsory for dogs to be treated against ticks before entering the UK. Taking your dog on holiday or importing/rescuing a dog from abroad, potentially opens the UK up to the risk of Babesia and Ehrlichiosis, both of which can be fatal to dogs.

Lyme’s disease

If detected and treated promptly, acute cases of Lyme’s disease can be resolved with a course of antibiotics. If left unnoticed, it can lead to a very debilitating, chronic illness and in the worst cases it can be fatal. The symptoms can sometimes last for a few days and fade away, only to reappear again several weeks or months later, by which time the disease may have spread throughout the body.

Symptoms:

Fever

Lethargy

Shifting lameness and arthritic joints

Swollen lymph nodes (glands)

Appetite loss

Later; kidney failure, heart abnormalities or problems with the nervous system

A tick may produce a classic bull’s eye lesion but more often than not with dogs, there may be no skin reaction at all. If you don’t see an engorged tick on you or your dog, you may have no idea there was ever one there. But if you have any reason to suspect a tick has been for a visit then it is vital to get your dog to the vet or yourself to the doctor, where the test for Lyme’s can be done and treatment can start as soon as possible if it has been transmitted.

Babesia

Babesia Canis has recently been introduced into the UK, with a few cases seen in Essex in dogs that have never travelled abroad.

It is caused by a protozoa, naturally transmitted by Dermacentor Reticulatus ticks which are found in the UK and the Rhipicephalus Sanguineus tick. The latter although rare in the UK at the moment, may become more prevalent with the removal of the need for mandatory tick treatment before entering the UK.

Babesia attacks and destroys red blood cells. As a result, the dog’s circulation is progressively less able to supply oxygen to its organs. The immune system dispatches antibodies to destroy the infected cells but they destroy many healthy cells at the same time, exacerbating the problem and worsening the anaemia.

Symptoms:

Fever (often higher than 104˚F/41˚C)

Appetite loss and weight loss

Increased respiratory rate

Anaemia (seen as pale gums) or jaundice (yellow gums)

Blood in urine

There is no specific treatment for Babesia in dogs, so a cattle drug is used off-licence. Treatment may not completely eliminate the parasite and affected dogs can remain long-term carriers.

Erhlichia

Ehrlichiosis is another tick-borne disease affecting white blood cells, caused by the bacterium Rickettsia. People can also suffer from Ehrlichiosis as a result of being bitten by an infected brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) but this is rare with only around 10-20 confirmed cases per year in the UK.

Symptoms:

Fever

Anorexia and weight loss

Stiffness and reluctance to walk

Blood abnormalities resulting in prolonged bleeding

Acute cases receiving appropriate antibiotics respond quickly, with body temperature returning to normal within 48 hours. In chronic cases, the haematological abnormalities may persist for up to six months, although clinically the dog will improve sooner.

Tick removal

When removing a tick, it is important to remove the whole tick including its head and not to aggravate it. Injuring the tick can cause infected fluids to be regurgitated and pass back into the dog’s bloodstream, increasing the risk of disease transmission.

Do not try to pull the tick off as it will result in the head parts remaining cemented in.

Forget the old- fashioned remedies of burning them off with a cigarette or freezing them, or smothering them in petroleum jelly.

The best way to remove a tick is to use a tick-removal tool. There are different products available but the O’Tom Tick Twister is highly recommended by teterinary professionals (www.otom.com).

How to use

1. Choose the appropriate size of tick remover for the size of the tick.

2. Slide the hook under the tick, flush with the skin, and engage the hook until the tick is held in place.

3. Lift the hook lightly and turn it two or three times until the tick detaches.

4. Check the tick has been removed intact and swab the area with antiseptic.

5. Dispose of the tick.

Prevention

Disease transmission doesn’t occur within the first 24 hours after feeding commences, so removing the tick as soon as possible greatly reduces the risk of infection. It is important to regularly check over your dog and comb through their coat. Small ticks may easily go undetected until they feed and become engorged.

As with everything, prevention is better than cure. There are numerous products available on the market which kill ticks promptly and also repellent collars.

Slightly dated now, but still a valid option, are the spot-on products containing fipronil. This pesticide kills ticks within about 48 hours of application, and continues working for approximately 30 days. It relies on the fleas and ticks taking a blood meal. Fipronil is waterproof and stays effective even after your dog has had a swim or a bath. However, it is recommended to avoid contact with water for at least 48 hours after application.

A repellent spot-on containing imidacloprid repels and kills ticks for up to four weeks. This is more commonly used on the continent against sandflies.

Monthly or three monthly tablets are available which kill fleas and ticks. These are palatable treats, easy to administer and there is no risk of the product being washed off and losing efficacy.

Repellent collars repel and kill ticks for eight months as well as killing fleas. They are water resistant but unfortunately are unsuitable for many working dogs that are at risk of catching them on the undergrowth.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

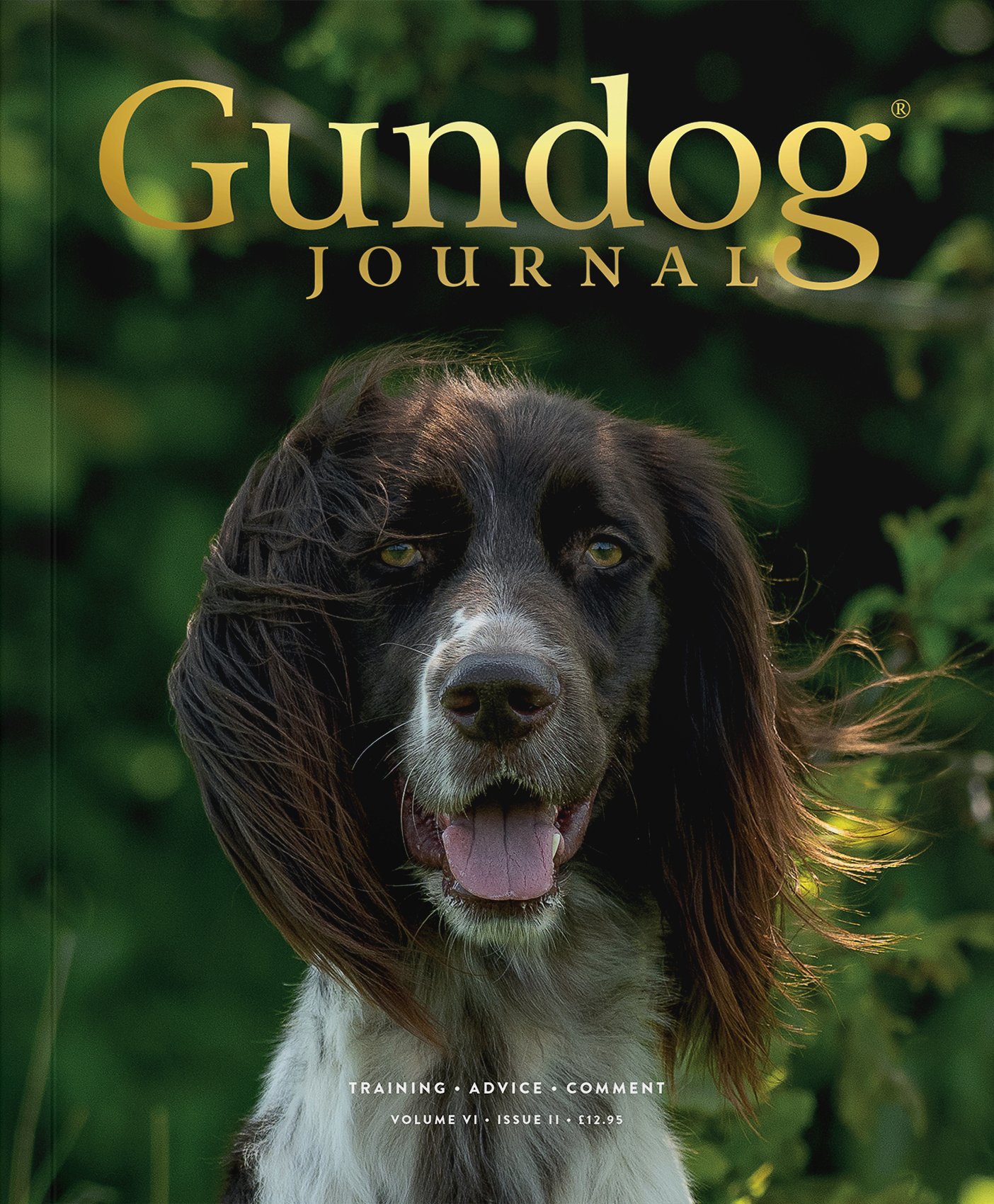

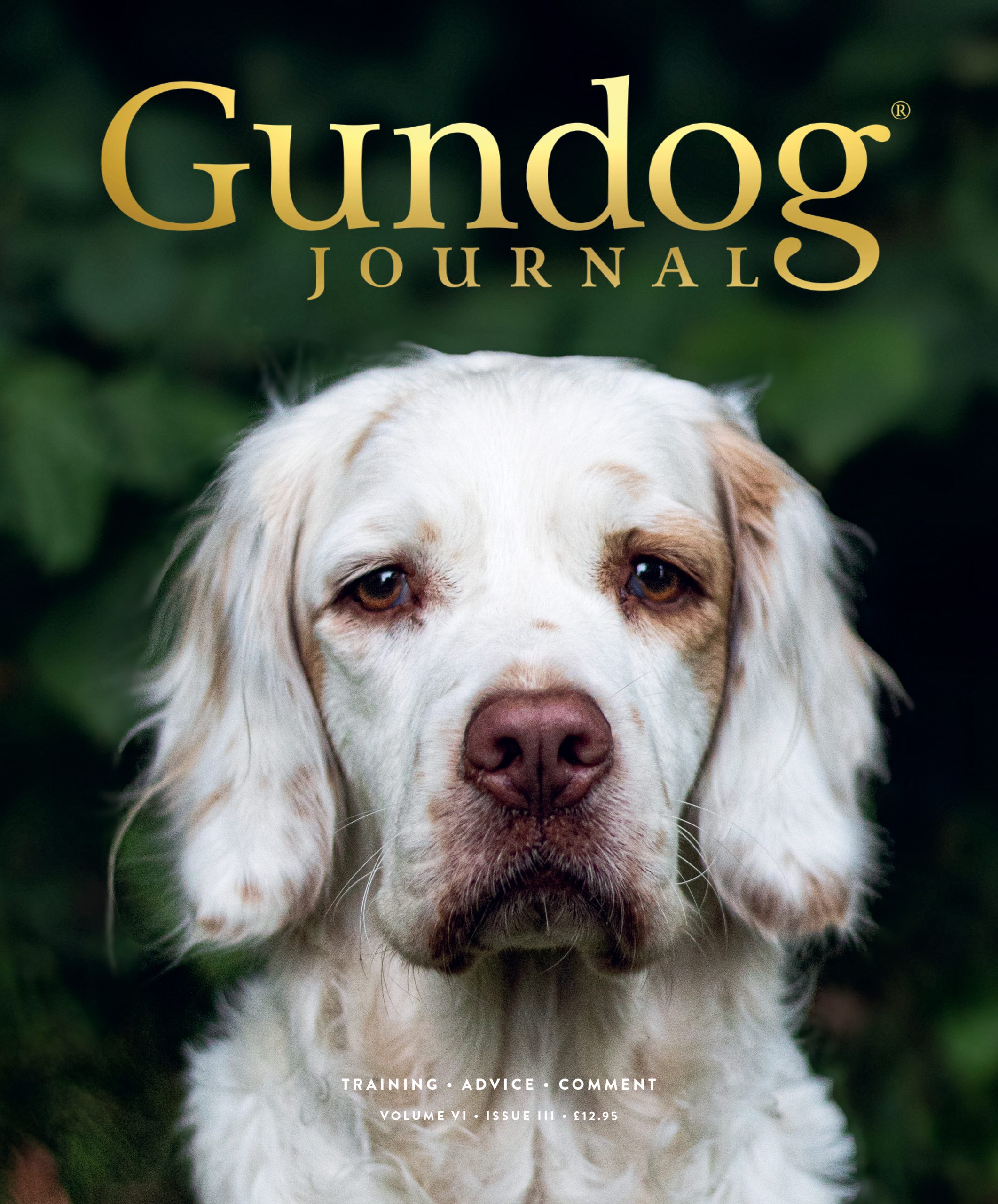

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.