Lumps and bumps

If you find a lump on your dog then acting soon could prevent a lot more trouble later on, as veterinary nurse Laura Keyser explains.

Dogs of all ages can develop lumps and bumps, some which may be fairly insignificant and some which can be fatal, and confusingly they can have very similar appearances. Masses can be broadly categorised as cutaneous, involving the skin, or subcutaneous (below the skin). Masses can also be mucosal, such as on the gums, lips or inner cheeks. There is no way we can tell if a growth is benign or malignant (cancerous) just by looking at it or feeling it. Often the dog isn’t bothered by the lesion, unless ulcerated, so they may not draw your attention to it. Therefore, it is important we check our dogs regularly from nose to tail and are meticulous when doing so. If you do find a lump, it is wise to seek veterinary advice, as early detection is key.

As vets, we get asked “what do you think it is?” on countless occasions, but sadly we don’t have crystal balls and we can’t predict the nature or progression of a growth. That is why it is always important to get a lump checked and the vets will usually recommend a biopsy. There are a number of ways masses can be biopsied.

Biopsies

-

Fine Needle Aspirates (FNA) are the least invasive method and can often be performed while the dog is still conscious. This involves the vet putting a hypodermic needle in to the mass several times and redirecting the needle to obtain a sample of cells from the mass, with or without applying suction on a syringe. The contents of the needle are then expelled on to a microscope slide using an air-filled syringe. The advantages of cytology by FNA include a minimally invasive approach, low risk, low cost and quick results. Some vets will look at the microscope slides in-house but most will send them off to a laboratory for a specialist’s opinion. The limitation of FNA is that the sample size is only small and may not be good enough quality. Therefore, they can sometimes be non-diagnostic or unequivocal, meaning that the sample may need to be repeated or a large biopsy may need to be taken.

-

Punch biopsies or Tru-cut (also known as needle core) biopsies allow slightly larger samples to be achieved. A punch biopsy is like an apple corer and usually a 4-8mm wide cylinder of skin and subcutaneous tissues are removed. A single skin suture is usually placed where each biopsy has been taken from. Needle core biopsies are useful for both cutaneous and deeper masses, and can also be used under ultrasound guidance to reach organs such as the liver. These are both generally performed under sedation or general anaesthetic.

-

Incisional biopsies involve taking a slice of tissue from the lesion and surrounding ‘normal’ looking tissue using a scalpel blade, hopefully providing more success in obtaining a diagnosis. Again, these are achieved in a sedated or anaesthetised patient. Once a diagnosis has been achieved, careful planning about how to remove the mass and a second surgery would then be required to excise it.

-

Excisional biopsies involve removing the whole lesion along with a band of normal tissue all the way round the circumference and also a tissue layer deep to the mass. The downside to this is that if incomplete ‘clean’ margins of tumour free tissue have been removed, a more radical revision surgery may be required to remove the ‘dirty’ scar and surrounding skin.

Diagnosis

Once a biopsy has been achieved, these are usually sent off to an external laboratory, either as microscope slides or samples fixed in formalin. At the lab, they will examine the slides cytologically or the sample histologically, and report back to your vet, surmising what type of mass they think it is and how the cells in the mass are behaving. Not all biopsies are 100 per cent conclusive, especially if the mass doesn’t exfoliate well, so it’s worth being aware that a different biopsy technique may have to be performed to obtain a diagnosis.

A diagnosis is important, firstly to differentiate the type of lesion, know whether it is benign or malignant, and if it has spread to other parts of the body. Secondly, you can plan if and when to remove it, what margins around it need to be taken and whether any adjunctive treatment needs to be carried out afterwards (e.g. chemotherapy or radiotherapy).

Staging

For malignant tumours, “staging” is performed to gain more information about the mass. This involves the TMN system, in which T = the tumour size, M = distant metastasis (spread) to other organs and N = lymph node involvement. Chest X-rays and an abdominal ultrasound, or CT scan if available, will be recommended to stage a tumour.

Approximately 20-40 per cent of submitted biopsy samples are reported to be malignant. The difficulty as previously mentioned is differentiating between them, for example a small red raised mass could be a benign histiocytoma, which may regress spontaneously, or conversely it could be a grade III mast cell tumour with only a seven month mean survival time. Just as a fatty feeling lump can be mistaken for a lipoma, but it may actually be a soft tissue sarcoma, which carries a very different prognosis.

Benign masses

The most common benign masses are the lipomas, which are soft, relatively mobile, fatty lumps. These are particularly frequent in labradors. They tend to be fairly easy to remove and can be shelled out from their capsule under the skin. They frequently do not cause too much of a problem unless they get particularly large and affect mobility, and are often removed for cosmetic reasons. There are however the more complex infiltrative types, which can weave in between muscle and fascia; they remind me of marble sponge cake at school, interwoven with fat and muscle. The infiltrative lipoma can prove much more difficult to remove, either taking them out piecemeal, but with the risk of recurrence within a year, or more drastic surgical measures need to be taken, including salvage procedures such as limb amputation.

Another common skin mass, more frequently seen in young dogs, is called a cutaneous histiocytoma. Histiocytes are a group of cells involved in the body’s immune system and they are the cells involved in forming histiocytoma. Over the first one to four weeks, they grow rapidly and can often become ulcerated and secondarily infected. Treatment only needs to be given if the dog is causing self-trauma. These harmless masses generally regress spontaneously over about three months. Topical steroid and antibiotic cream, and a buster collar can be used in the interim. If they are still present after that, complete excision is recommended.

We also see many other benign lesions in our gundog breeds, including papillomas (warts) sebaceous adenomas from oil producing glands in the skin, follicular cysts from blocked hair follicles, skin tags (acrochordon) and abscesses. For all of these, complete excision should be curative. Care must be taken as malignant versions of these can occur and can only differentiated on biopsy.

Malignant tumours

The most common malignant skin tumours in dogs are mast cell tumours, soft tissue sarcomas, squamous cell carcinomas and melanomas, amongst others.

Mast cells are immune cells which are normally involved in allergic reactions and cause histamine release, hence why we take antihistamines if we are stung. Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumours (MCT) need to be graded as described previously. The grade is the best predictor of whether follow up testing or additional treatment is required. Low grade tumours are usually cured with complete excision, whereas high grade tumours are more likely to recur in the same place or spread to distant sites in the body and require adjunctive treatment. MCTs can spread to lymph nodes, the liver and spleen. Due to histamine release, other side effects can include urticaria (hives) and gastro-intestinal signs (vomiting and diarrhoea). Chemotherapy is usually recommended to extend survival time.

Soft Tissue Sarcomas are often slow growing and solitary masses but may be firmly attached to the skin, muscle or bone that they are associated with. Approximately 20 per cent of cases spread via the blood stream to the liver or lungs. Wide surgical excision is required as they often have finger-like projections of tumours cells spreading outwards from the main lesion. If only a narrow excision can be achieved, chemo or radiotherapy should be used after surgery.

Squamous Cell Carcinomas (SCC) arise from the epithelial cells of the skin. There are quite rare in dogs compared to cats (think of sunburn on the tips of white cat’s ears). Certain breeds are predisposed including beagles, dalmations and bull terriers, likely due to their light skinned and sparsely haired portions of skin. Short-coated dogs who spend a longer amount of time outdoors also have a higher incidence of SCC. Most appear as firm, raised, ulcerated plaques or nodules. Treatment involved removing the primary tumour. If incompletely excised, radiotherapy can be used to prevent regrowth. SCC can occasionally spread to the local glands and lungs. These can be challenging to treat and may require combined surgical and medical treatment.

We all associate melanomas with skin cancer in humans. Malignant (cancerous) melanoma occurs far less frequently in dogs but they can be aggressive in nature. Benign melanomas are cured with surgery, whereas malignant melanoma tumours can spread to local lymph nodes and the lungs, therefore additional treatment with chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy is recommended.

Surgical excision

Ideally the first surgery should be the only surgery, so careful planning is required to ensure the mass is removed in its entirety. Usually a border of 2-3cm of healthy tissue around the tumour should be removed and one layer (or fascial plane) deep. Depending on where the mass is, one layer deep may only involve fat or muscle, but if the mass is over the rib cage or on a limb for example, mass removal may involve rib resection or digit/limp amputation. Skin flaps and skin grafting techniques can be utilised to remove a lesion over an area where there isn’t much spare skin. These can be very complex surgeries and should only be undertaken by an experienced Veterinary Surgeon. You may wish to discuss referral to a local specialist centre if this is required. Sometimes closing the whole wound may not be possible and “debulking” the majority of the mass may be the only option. A portion of the wound may have to be left to heal by secondary intention, so they granulate and contract down in size over several weeks of dressing changes.

Chemotherapy

Cancer cells replicate in an uncontrolled manner and can be found in lymph nodes and other organs, e.g. the liver, spleen and lungs after the primary mass has been removed. Chemotherapy can be used to kill rapidly dividing cancerous cells. This however is in a non-selective way, so not only does it affect the cancer cells, but also the gastrointestinal tract and bone marrow. Some chemo drugs can be given in tablet form at home, others need to be given in an injectable form by your Vet or under the guidance of a specialist oncologist.

Chemo can be costly, time-consuming; involving regular trips to the vets for blood tests and treatments, and dog owners need to be aware of the potential side effects and toxicity risk to the family. Children and immunocompromised adults should not be in close contact with a dog while undergoing chemo. Contact with all bodily fluids should be avoided for a minimum of five days after each round of chemo; faeces should be double-bagged and any urine or vomit accidents soaked up with absorbent towel and cleaned with bleach.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy can be used after a mass has been removed, to mop up the remaining microscopic disease. Radiotherapy causes cell death when the cells are trying to replicate, so rapidly growing cells will see an earlier response, but slow growing tumours will see late effects. Usually a CT scan is performed to create a computer model so the oncologist can direct the dose of radiation to the target area. The radiation is then given over 20-25 doses (or fractions). There are only a few centres in the UK, which offer this, mainly the University centres.

Visual monitoring of masses is not enough to make a diagnosis. Cancer can only be diagnosed at a cellular level with a biopsy. The “let’s wait and see” approach can leave people caught out, with lesions being unexpectedly malignant or masses growing so rapidly they make removal problematic or even impossible. It is always recommended to check out any new masses, or those that have been previously tested but are growing or changing in appearance.

If they are detected and removed early, when they are small and clean margins around the mass can be achieved, the prognosis is often more favourable and the dog may not require any further treatment.

If you see a mass, do something about it.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

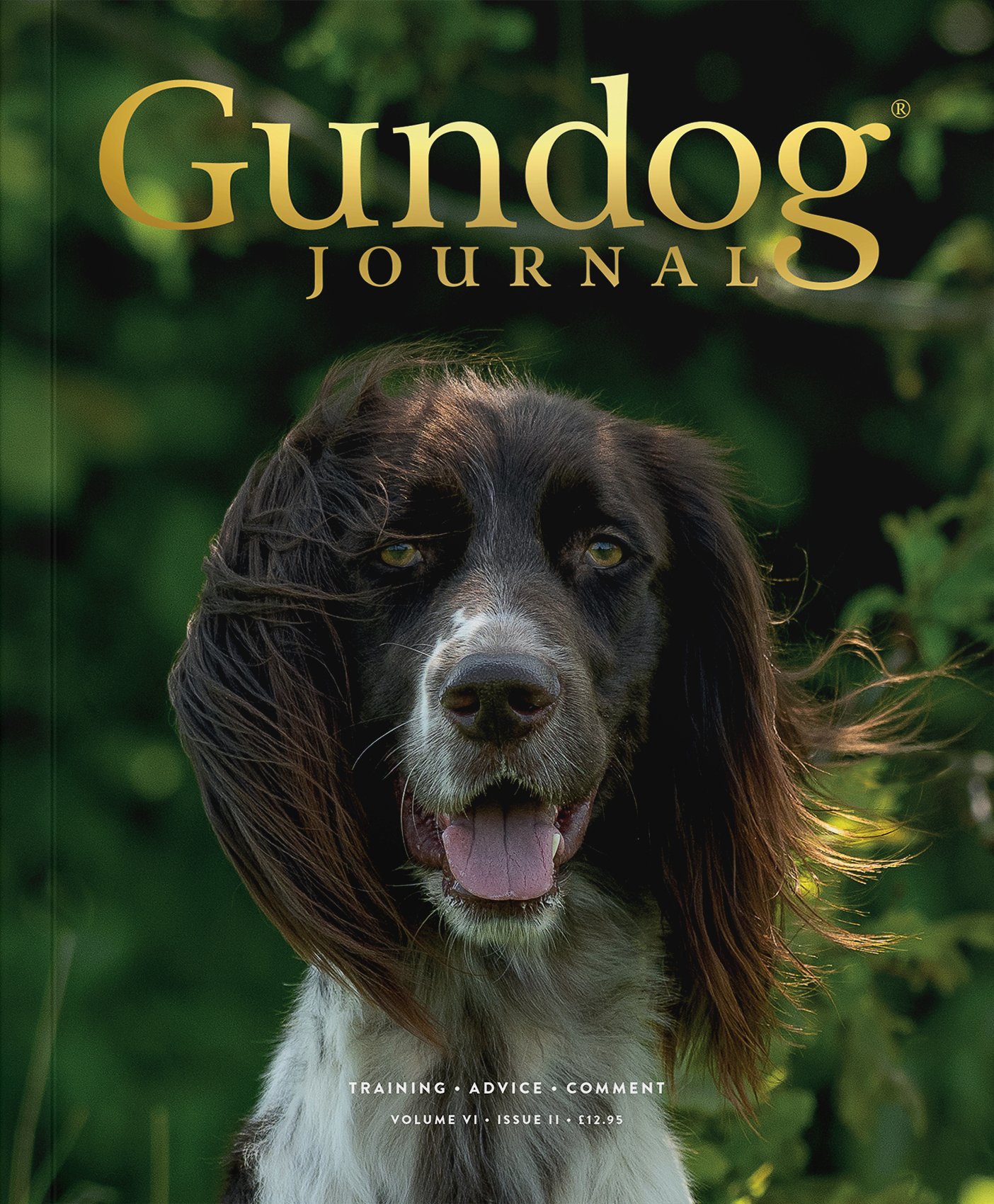

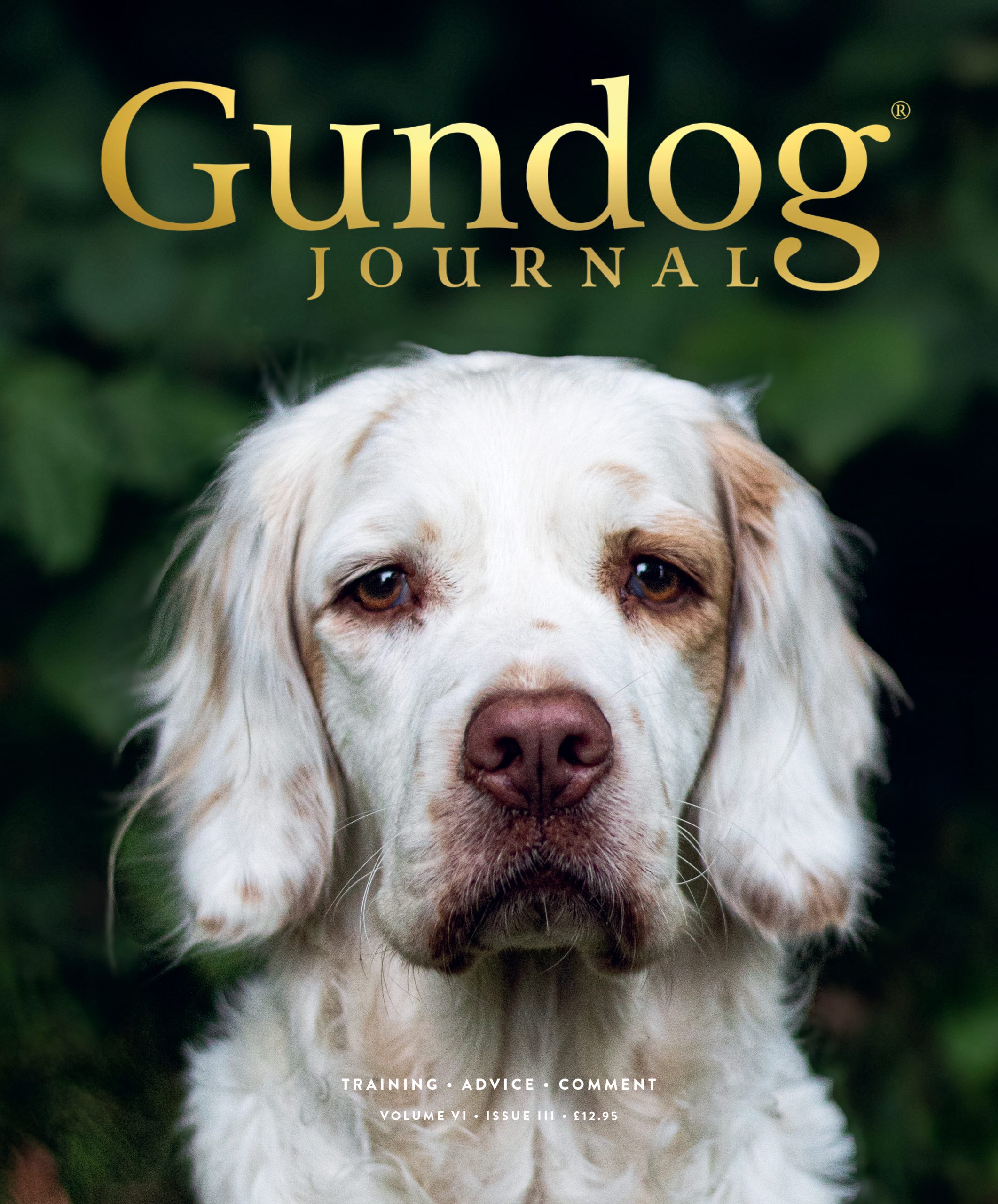

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.