Hunting dogs

The ancient brotherhood between dog and human runs deeper than that between any other species...

It starts where it always does, on the rocks. Ochre figures on a stone wall, spears and bows poised. In some caves there are deer in front of them, in others wild sheep etched into the living rock. And around them are shapes with sharp muzzles and curled tails, hunting dogs of the ancient past, leaping with their masters.

They still sing, these images of our most ancient partnership. Dogs threw their lot in with us long ago and it’s still the best brotherhood to bridge the gulf between species. They will sit and watch a fire by our side, have hunted with us, guarded our homes, gone to war, served as willing companions for the lonely and old. This thing runs deep.

Some think only of shooting and the beautiful work done on birds by spaniels and retrievers, but there is so much more to the partnership than that. In a flash I’m in the high jagged mountains of Lesotho, on the roof of Southern Africa. Here we chanced upon a hunter and his small pony, and trailing behind them in the dust was Kotsi, with his hawk eyes and lip marred by a scar. Basotho people expect their dogs to guard the camps at night against leopard coming down off the rocks, or from bandits. If small game gets up his boss might try to take it down with a precarious old shotgun, and nine times out of 10 it will be his dog that makes the difference between success and failure. At other times the pack must trail a stock-killing leopard, and everybody knows what will happen when they meet. Kotsi was an old dog in a game where many die young.

In New Zealand, for all its First World ways, things are much the same. All over the country there are still men who take to the valleys with dogs to chase wild pigs. Each dog has a role – to find, to bail or to hold – and they put their lives on the line to do it. Anyone who knows these hills has heard of hunters who have carried a gored dog out and paid a fortune to save him, such is the bond between them. I know one such man myself, and asked him after all the bills were paid – to no avail – if it was worth it. The reply was a long pause and a hoarse ‘yes’ that spoke volumes.

There are deer dogs here too. I hunted not long ago over Pat, a German shorthaired pointer belonging to a professional stalker. Her first deer was a wounded sika stag that she pulled down by herself at just six months of age. Since then she has been involved in literally hundreds of bagged deer, but at 12 she still trembles at the sight of quarry.

I’ve seen them too in the Alps of Austria, forester’s dogs of unusual colour and cast. The Bavarian mountain hound is growing in popularity, but there are others that are seldom heard of outside those sombre valleys and high meadows – the various Bracke breeds, Hanover hounds and others. My maternal grandfather roamed these forests with a hound named Vetter, which translates as ‘cousin’. Their master wearing green loden and felt hat, carrying his bock rifle or stutzen, these are stalking and blood-tracking dogs of unparalleled talent. They ply their trade on roe, red, fallow, boar and chamois among the fields and peaks of that spectacular country.

Down in the lowlands of Europe there was Liesl, the little wirehaired dachshund known as a teckel. Her job was to run a ferocious beat around wild boars well over 10 times her size. With bristles up and anger in their eyes, the big pigs are lethal, but the little dog somehow stayed clear. They buy time, gambling for each second with their lives, waiting for their master to come. If there is an animal in all the world with a bigger heart than a teckel I have yet to see it.

They have their opposite numbers in the most unlikely of places. In the dry, desert country of Southern Africa you can find Jack Russells on duty, keeping their professional hunters company and following-up on wounded game if the need should arise. Why the little terriers should be so good at it is hard to fathom at first, but, like the teckel, their size is less of a drawback than it might seem. Over lunch at a waterhole one day, I put it to a career professional who is never without a terrier at his side. He summed it up nicely. “The white in their coat makes them easy to see against typical bush or sandveld, and with those short legs they’re easier for the hunting party to follow than a wide running hound. A big dog will often put wounded game to flight, but little guys keep the animal alert and pinned, not alarmed enough to flee. It can make all the difference.” A Jack Russell’s face hanging out the side of a khaki Land Cruiser is still one of the defining images of an old school safari.

Then there’s Natan, a little Vizsla who lives his life on the vast pampas of Argentina. He’s a fine perdiz dog, able to point and follow the unpredictable partridges (actually a species of tinamou) as they weave through the scant grassland, but it is with the Russian boars released there a century ago that he excels. He’s a finder, whose job is to locate scent and lead the pack to a boar, no doubt backed-up somewhere in a nightmare of thorn.

The list goes on, including a shorthair named Saxon who shared adventures with me across countries and whose story has been written about elsewhere. Looking back, the question must be asked – what do all these dogs have in common? Despite their differences in breed, the qualities each brings to the game turn out to be remarkably consistent. All of them push far beyond the norm, an unrelenting drive that never waivers. They don’t just want game, or have enthusiasm for the sport. They burn. They want it not because of lessons they have been taught but because it’s simply who they are.

They’re not robots following orders, but arch-predators listening to voices we will never hear. Watch them when they hit scent and it’s clear that they work in a trance, the instinct of a thousand generations unfolding without thought. Even then, a brilliant nose, good instincts and drive cannot explain why stalking dogs make the mark on people that they do.

Long after the trophies have grown dusty on the wall, hunters still talk about them with a quiet sense of awe. The panting face cut to pieces by thorn, but still on the trail. Pads worn bloody on rock, but still running. And at the end, an ageing body weary with old wounds, that rallies through the pain and insists with dim, faded eyes. ‘Just one more, Boss. I can do it.’

We see in them the best of ourselves. It is greatness of heart we remember them for, and why we cannot let them go. The high times with a stalking dog tend to be short. By the time they’ve learned a few things, a couple of seasons have come and gone. When they finally come into their own they have a handful of years – no more – before old age starts to creep in. It passes in what seems like an instant. Like all of their kind, they are brief. It’s their only real fault.

I do my best to be with them when they go into the twilight, even though it’s sometimes grim. It’s sentimental, but I prefer to believe that if the tables were turned they would not abandon me at the last. As they fade I hope they dream of running, of the days when they were young and strong and the world was theirs.

We tell ourselves that it’s a mistake to grieve for an old friend, that we should be glad that such a great heart ever lived. That’s true enough, but soon – too soon – I’ll have to brace myself for another of these moments, and the gallery of lost friends will be a little bigger. When you lose a dog you discover that there are two kinds of people, those who say ‘it’s just a pet’, and real people. It’s easier if you accept that you never stop missing them, and that a certain chapter of yours has closed.

Given the harsh price we must pay, why do we put ourselves through this miniature of our own life, this unsubtle allegory of the span we too are given? Because no other creature invites us so freely into their inner world, and no other wants so fervently to be part of ours. Because when Odysseus returned to his palace dressed in rags after years of war he was taken for a beggar. Only Argos, his hunting hound – now old, broken and despised – recognised him with joy, and the soldier king turned so none would see his tears.

Perhaps one day when the hollowness has faded, when the whistle hanging on its hook by the door and the empty kennel seems less forlorn, there might be another pup with sweet breath, pouncing on your hand and staging mock fights with your fingers. Not the same, of course, and you never know how this one will turn out. He’ll have his little peculiarities, to be sure, but right now all he wants is to be with you, and the world is a brighter place for it.

When you bring a hunting puppy home you’re striking a deal that will, with luck, last a decade or more. Dogs already know in their bones what the contract is, it was written on stone walls long ago – ‘Brother, there is no adventure too big for us, I will follow you until I can follow no more.’

The rest… well, the rest is up to you. We don’t own these dogs, we live up to them.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

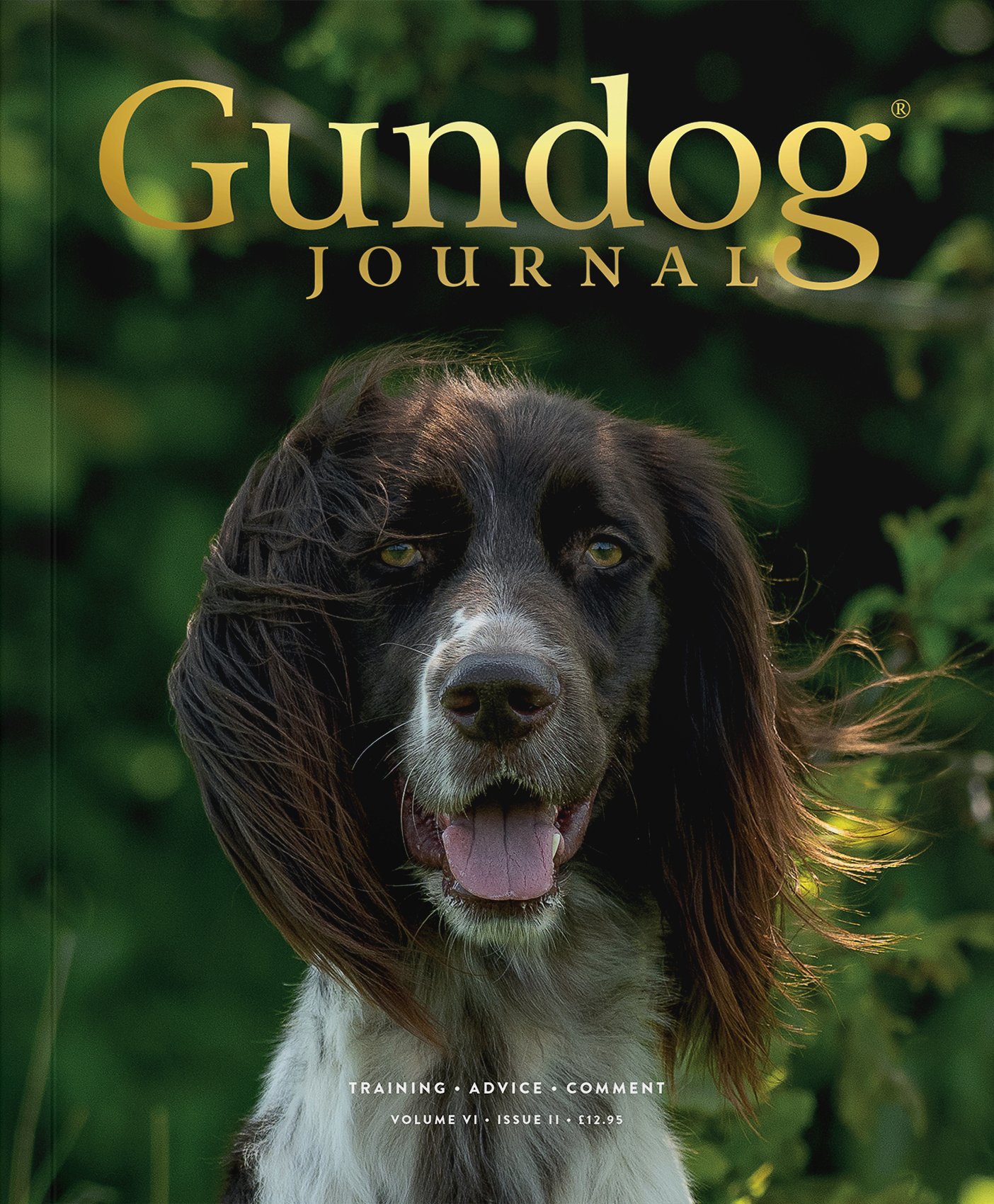

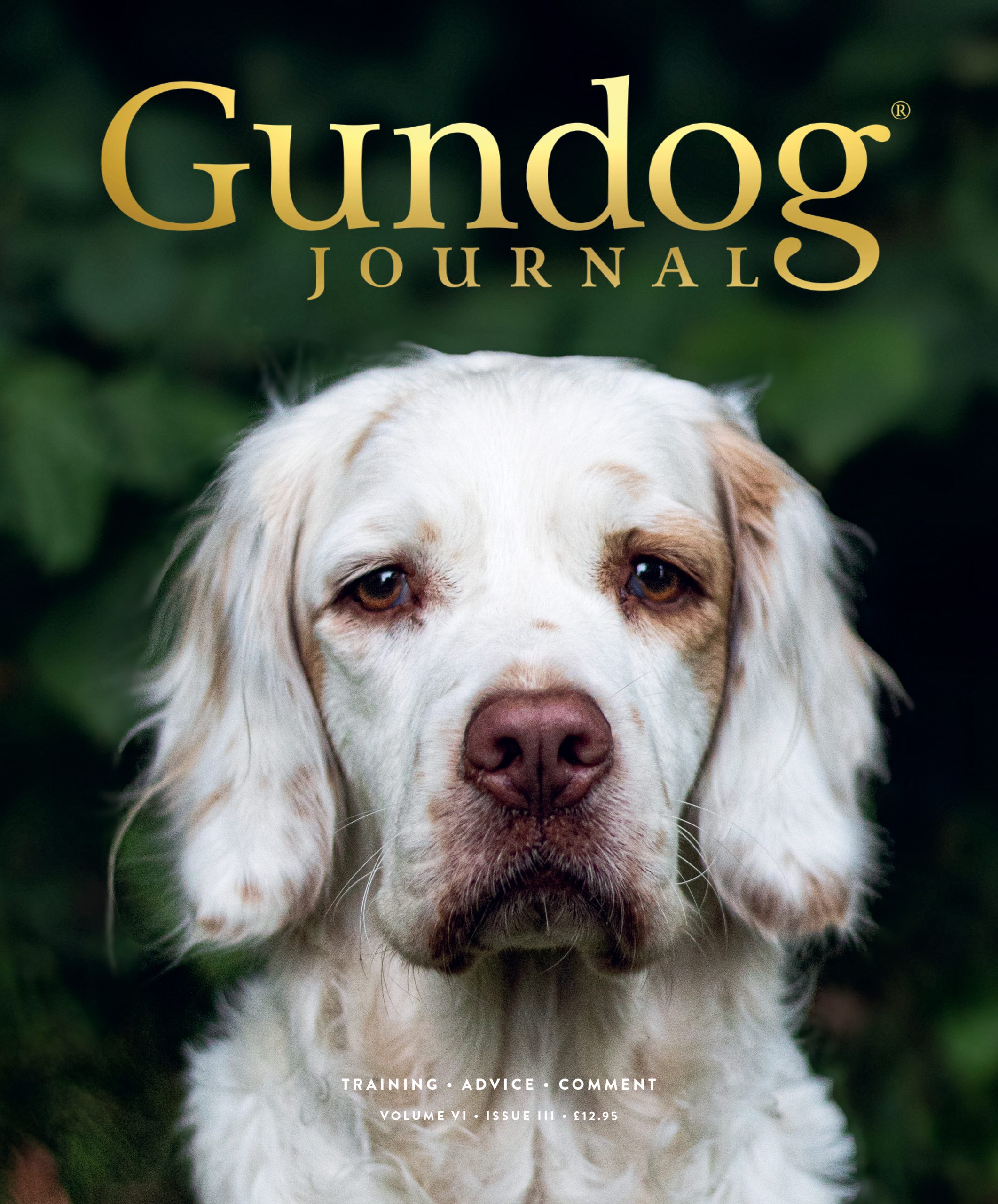

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.