A peep into the past

David S. D. Jones provides a fascinating insight into the history of our working relationship with man’s best friend.

Sportsmen have been using specially trained dogs for hunting purposes in Great Britain since Roman times. Dogs were not only used for pursuing deer, wild boar and other quadrupeds but also in connection with falconry. Later, in the Medieval period, small dogs were employed when decoying ducks, spaniels for tracking down and netting partridges and other gamebirds, and greyhounds for coursing hares and deer.

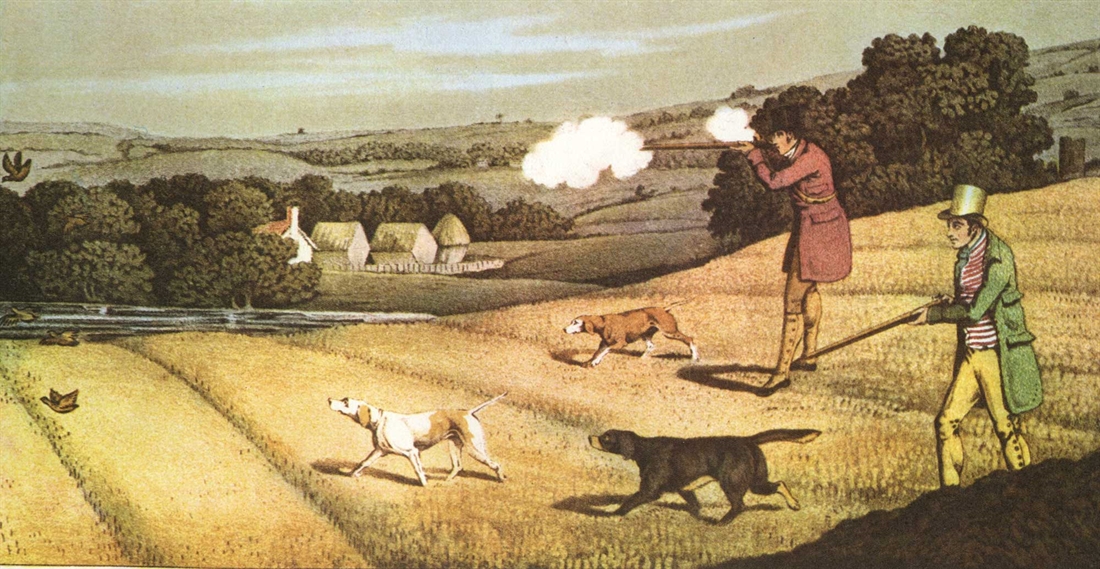

It goes without saying that when game shooting was first introduced during the late Tudor era, sportsmen started to use dogs to retrieve fallen gamebirds. Shooting was something of a minority sport at this time and was considered unsporting by the aristocracy of the day who preferred hunting and falconry. Indeed, at this time, birds were shot on the ground rather than in the air.

Gundogs really started to come into their own following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 when King Charles II introduced the French practice of shooting at flying birds to England and Wales. Spaniels and ‘setting dogs’ (early setters) were used both to flush and to retrieve partridges, pheasants and other gamebirds. Such dogs were fairly thin on the ground, though, as shooting was restricted by a property value qualification to members of the aristocracy, major landowners and large leaseholders, their eldest sons and gamekeepers.

Shooters continued to use field spaniels (a term then apparently applied to various types of spaniel) and ‘setting dogs’ or setters as gundogs until the early 18th century when the pointer was introduced from Spain by army officers returning from the Continental wars around the time of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1715. These breeds were augmented during the late 18th century by the Clumber spaniel – imported from France by the 2nd Duke of Newcastle and initially bred on his estate at Clumber Park in Nottinghamshire – and the Newfoundland retriever, the first of which were brought into the port of Poole in Dorset by sea captains returning from Newfoundland and sold to local sportsmen.

Over the course of the 19th century, a number of additional breeds were utilised for shooting purposes. In particular, the labrador retriever, the curly coated retriever, the flatcoated retriever, the Sussex spaniel, the field spaniel (later split into cocker spaniels and springer spaniels, depending on size), the Gordon setter, the Irish setter and the poodle. Setters and pointers ceased to be used on many low-ground shoots and became the principal working gundog on grouse moors, along with certain retrievers.

Sportsmen and gamekeepers became increasingly interested in setting high standards for gundogs following the introduction of the breech-loading shotgun in the mid-Victorian period, which enabled an individual to shoot a large bag of game within a short space of time on a driven shoot. Indeed, the changeover from walked-up to driven shooting at this time created an insatiable demand for elegant, well trained sporting dogs.

Seeing a business opportunity for selling high quality gundogs to sportsmen, William Rochester Pape, a Tyneside gunmaker, pointer breeder, falcon dealer and inventor, organised the first dog show in Great Britain at the Corn Exchange in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne in 1859. It was a ‘dogs only’ event with two classes, one for pointers, the other for setters. The prizes were ‘best quality Pape guns’ valued at between £15 and £20. At the end of the show, many of the dogs were offered for sale at prices ranging from £10–£100 (£6,000 in today’s money) for pointers, and from £10–£300 (£18,000 in today’s money) for setters.

Field trials to test the ability of working gundogs in competitive conditions were introduced shortly after the early dog shows. The first organised trials were held at Southill, Bedfordshire in 1865 and were quickly followed by similar events in other locations throughout the country. Some of the initial trials were primarily for pointers and setters, which, apparently, competed under live shooting conditions. Gundog trials were very much the preserve of country gentlemen until the late Edwardian period when the Gamekeepers National Association, which had begun life as the Dumfriesshire Gamekeepers Improvement Society, set up an annual programme of trials for the benefit of keepers and other interested parties which has continued until the present time.

In order to promote ‘best practice’ in the gundog world, Sewallis Shirley, MP for Co. Monaghan, and a number of other gentlemen formed the Kennel Club in 1873. The principal aims of the organisation were to set up a consistent set of rules for governing dog shows and field trials, to maintain a register of pedigrees of dogs and to improve standards of hygiene at shows. The club published its first stud book in 1874 and first monthly register of dog names in 1881. In 1939, the club acquired the world-famous Cruft’s Dog Show, founded in 1891, which continues to host the Gamekeepers’ Ring for working gundogs.

The training and breeding of gundogs was traditionally carried out by gamekeepers. Indeed, keepers werecertainly training pointers and setters for shooting purposes during the 18th century. Purpose-built keepers’ cottages constructed at this time normally had a kennel block adjacent and often of a high standard. The dogs were generally fed on barley meal and mutton greaves rather than fresh meat. Many keepers made up their own medication and elixirs for their charges using herbs and other natural products.

Gundog management became increasingly specialised from the 1870s onwards. As a result, many large estates employed a kennelman, dog boys and, occasionally, a dedicated trainer to look after the shooting dogs, all reporting to the Headkeeper. ‘State of the art’ kennels were built with heating, wooden dog beds, grooming and food preparation facilities, and an exercise yard surrounded by ornate iron railings, usually near the headkeeper’s house or adjacent to a beatkeeper’s cottage.

Kennel compounds often also accommodated bull mastiffs which were used by gamekeepers when out on night patrol in pursuit of poachers, and terriers, kept for ratting purposes. Some sporting properties even developed their own strain of gundog such as the ‘Eaton’ strain of retriever which was in use on the Duke of Westminster’s Eaton Hall estate in Cheshire and at Normanby Park in Lincolnshire prior to the First World War. Indeed, upon its death, a much loved and loyal gundog would often be buried in an estate pet cemetery with an appropriately worded headstone.

Contemporary sources indicate that up until the late 1930s many of the larger sporting estate kennels housed from 30–60 gundogs at any one time. For example, in 1922, the 3rd Earl of Durham maintained a kennel of nearly 60 labradors, spaniels and flatcoated retrievers in addition to ‘night dogs’ for security purposes at Lambton Castle in Co. Durham, while the 6th Duke of Portland never kept less than 30 labradors at Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire at this time.

Surviving accounts for the 4th Duke of Sutherland’s estate at Lilleshall in Shropshire dating back to the Edwardian period provide an insight into gundog kennel costs at the time. For example in 1901 the Duke purchased four Clumber spaniels for the sum of £7-17/6d (£625 in today’s money) each, and one mastiff for £6-6/- (£6.30).In 1909 he bought four Clumber spaniel pups and tworetriever pups, all at £2-2/- (£2.10) each, paid each of his 12 gamekeepers a quarterly allowance of 19/d. (97½p) for the keep of two dogs, and purchased two bottles of whisky at 3/- (15p) each for his retrievers – presumably for medicinal purposes. He also awarded the sum of £1 to Gamble, one of his keepers, whose retriever puppy ‘Will’ had won first prize in the estate field trials.

Some leading sportsmen continued to maintain dedicated gundog training and breeding facilities until the mid-20th century. Lord Rank, for instance, ran a large kennel establishment on the Sutton Scotney estate in Hampshire from the mid-1940s until his death in 1972. A keen supporter of the Utility Gun Dog Society, he specialised in breeding and training labradors and pointers and not only competed in field trials throughout the country but also hosted trials at Sutton Scotney. He owned between 50–70 dogs at any one time and employed a kennelman, a head dog handler- trainer and two assistant dog handlers to look after them!

Since the end of the Second World War, however, gundog breeding and training in Great Britain has become an increasingly specialised discipline and today is carried out by highly skilled practitioners, both on a professional and an amateur level. Indeed, few gamekeepers now have either the time or the resources to operate a gundog kennels in addition to their day to day work, other than on a few large sporting estates where a dedicated kennelman is employed in the game department.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

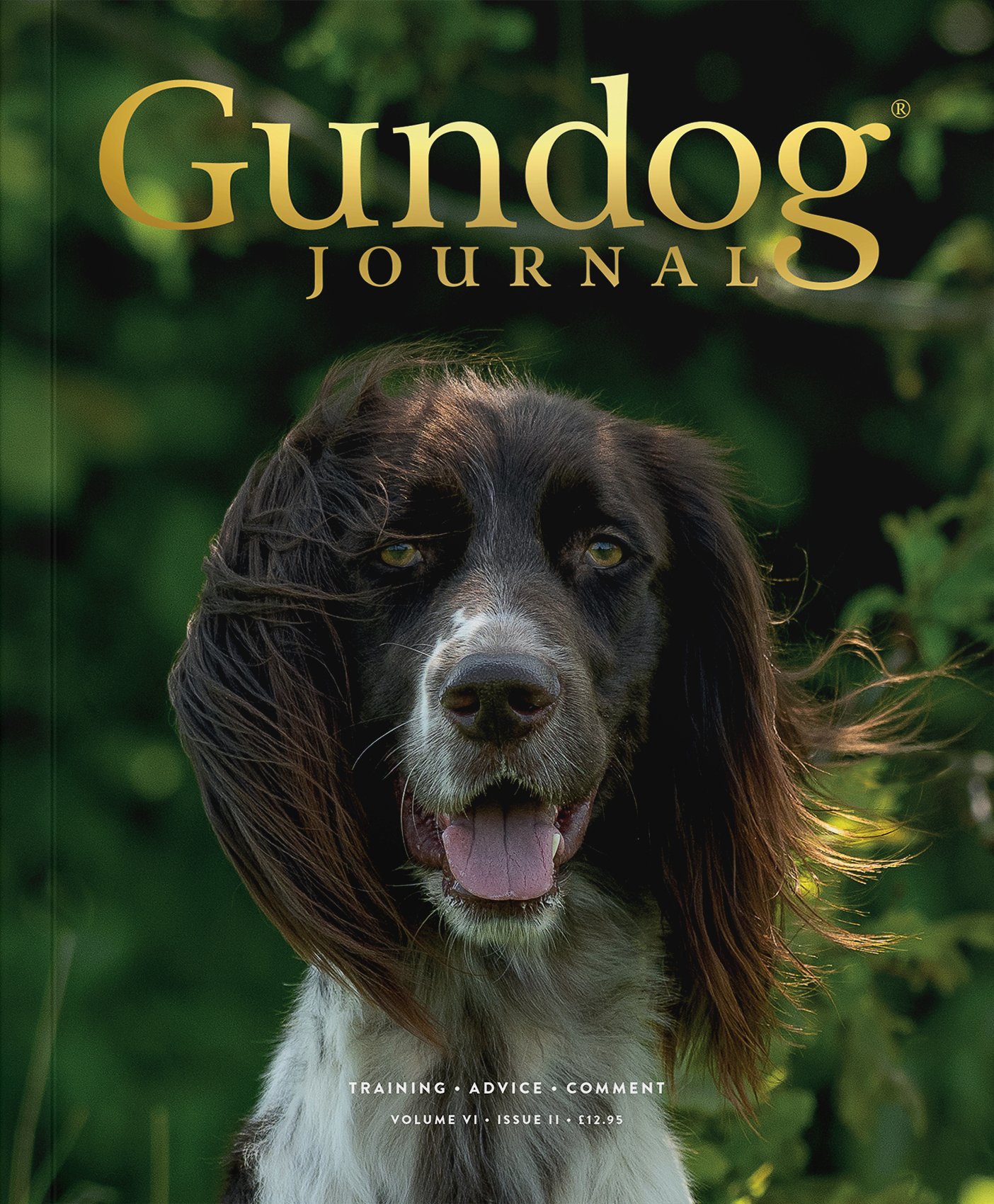

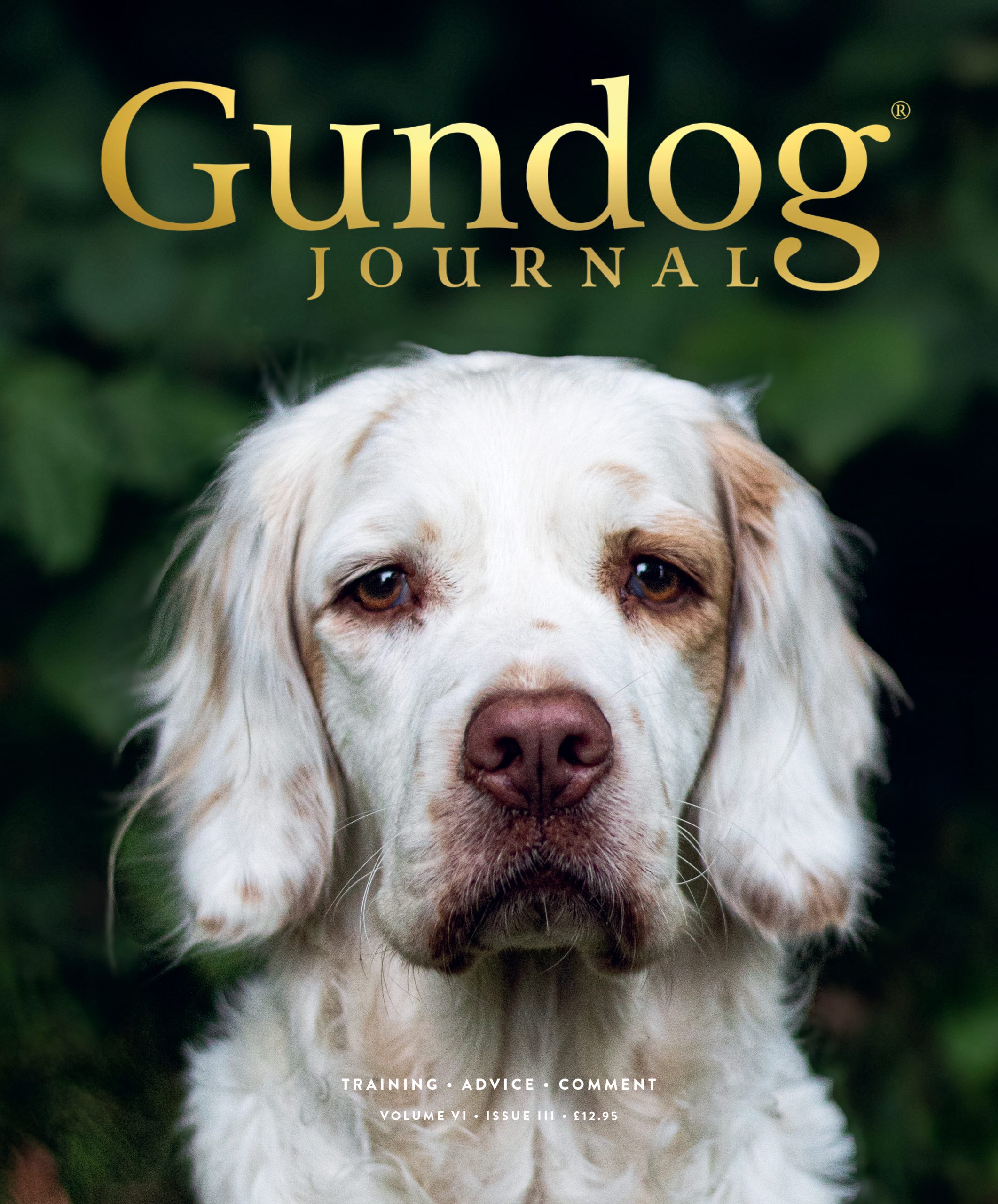

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.