Dogs for grouse

The moors provide a very different challenge from lowland picking-up. Here, Andy Robinson from Whaupley Gundogs explains how to prepare your young dog for this unique sporting environment.

On the face of it, grouse moors are an attractive and encouraging place for a young dog. Nice terrain, good weather, fairly easy cover where you can nearly always see your dog, and the retrieving of a small gamebird over short distances are all plus points. In reality, however, at times they can be quite an unforgiving place for a young and inexperienced dog. Heat, occasional poor scenting conditions, steep hills, heather and competition from numerous other dogs, are among the things that can at times make things challenging. In pointing out some of the potential pitfalls of taking a young dog out on a grouse moor, I hope not to paint too bleak a picture. Rather, if you are aware of the potential difficulties you may encounter on the day, you can then do the preparatory work in the form of training prior to the first shoot day.

Noisy and unsighted

Even if your young dog is well trained, there are things worth considering before you take that dog onto a grouse moor for its first outing, especially if you’re intending to use it as a peg dog in the butt. Pheasant shooting is very visual. A dog sitting close to you can see everything, often from the time that the pheasant leaves the cover until the moment it is shot and falls near the Gun. Some dogs find this very easy to cope with whilst others are over-stimulated by it and can start to fidget and even become noisy. A gundog on a grouse moor will often have a very different viewpoint and they may well see very little until the drive is finished. If you are sitting out at the back picking-up, you will have grouse flying past you but if the dog sits in the butt with you, it will only see your bottom half. Whilst some will find this easy and relax, others who would normally be steady when they can see, start to fidget and get very uneasy. It is a difficult thing to train for but if you can go into a butt with your own dog to concentrate on that alone for the first time whilst someone else shoots, that will certainly help. You should have no shortage of people volunteering to shoot for you!

Another point worth considering is the noise in the butt. If you have ever ducked down below the level of a butt whilst someone else is shooting, you will have been surprised at not only how noisy it is in there but also what a large concussive effect is generated from the shotguns. You can feel the effect of it if you are down at your dog’s level – it feels like a shock wave bouncing around you. This must be alarming and unsettling for a young dog if they are not used to it. So often people blame excitement or temperament for a dog not settling and making a noise on the peg, but that can be too simplistic a reason. It can range from anxiety, fear, stress, excitement and anticipation, and throwing a young dog in at the deep end too soon.

The other option is to leave the dog outside the butt itself, but there are safety implications here for the dog. Not forgetting that suddenly everything becomes visible again with all the issues that can bring. I do not want a grouse butt to sound like a minefield, but they are not places to take an inexperienced dog without thought and careful introduction.

Beware the competition

Once the drive has finished, you are eager, either as a Gun who has shot some grouse or a picker-up, to get your young dog working and finding shot grouse. However, you may well be faced with another problem.

Most larger grouse moors have four or more people picking-up, some of whom may well each have up to 10 or more dogs. Keepers in the line, flankers, loaders and other Guns will also have dogs and the result can sometimes be a scrum of dogs, competing with one other and confusing the issue for people wanting to check each bird is picked. It is sometimes not easy to quietly work your young and inexperienced dog in that environment and they become either distracted or worried by it. If I am in that situation, I try and work my dog quietly away from the hurly burly of dogs and people and find somewhere where I can allow it to work at its own pace with minimum interference. For a first-timer on the moor, it is often better to set up a retrieve where the dog will succeed and build its confidence rather than let it hunt endlessly for no reward.

The mystery of scent

The subject of scent was covered extremely well in the first edition of this journal. Perhaps the most certain thing we know about scent is we don’t know much about it. There are days on a grouse moor where it is perfectly obvious that the scent is very good and all the dogs are finding it very easy to find shot grouse. However, there are other days when they cannot seem to find anything. It is easy, though, to confuse the apparent lack of scent with other factors. I often allow myself a smile when somebody says to me that “the scent is awful” when actually it is the fact that it is a blazingly hot, still day, the early season dogs are tired, overhot, unfit and their tongues are falling out of their heads. That is what is making them struggle to find the birds, not the scent or lack of it.

Early in the year there are days when the heather is covered in pollen and everything from your boots to the dog is covered in a fine yellow dust. When it is warm like this, the dogs can really struggle to find game. At other times the dogs can draw onto a shot bird from phenomenal distances. The most important thing is to give the dogs time to work it out and pay attention to the wind. When looking for lost birds it is often a good idea to allow all the Guns, helpers and dogs to leave for the next drive and wait for a few minutes to allow things to settle down. It is then common to find the birds very quickly. This may be because a lot of the distracting scents have gone and there is less disturbance around the missing grouse.

I find the best approach, regardless of whether scent appears good, bad or indifferent, is to take things slowly. Do not walk round and round the area where the bird is meant to be but stand just slightly away and allow the dog to work.

The one form of scent dogs never seem to have a problem with is rabbit scent and when faced with finding a live rabbit or dead grouse, most dogs find the rabbit irresistible!

Patience is a virtue

In lots of shooting disciplines there can be long periods of relative inactivity, followed by short bursts of intensive activity. This is possibly more exaggerated on a moor. One day, several years ago, I actually timed it (I must have been slightly bored!). From leaving the vehicles we walked with the dogs at heel for 15 minutes to where I was going to sit out behind the Guns – most of this time was taken with me constantly reminding five cockers that they really did know how to walk at heel!

Once sitting out in the heather with the dogs around me, we sat for 35 minutes whilst nothing appeared to happen. The shooting lasted for about 20 minutes before the drive started to end, initially with one horn to say not to shoot forward anymore and only shoot behind, and then with the second and final horn to stop shooting completely. The dogs had then been sitting for around 55 minutes before being cast off. Then they free-hunted for about 20 minutes, picking grouse until we returned to the vehicles. We did four more drives that day and the same process was repeated. That is a lot of time for a dog to sit down and it is often said that the most important discipline for a gundog is to learn to sit on its backside. This length of time doing nothing and learning is a difficult thing to train for, but the early work done on basics will always pay dividends. Some dogs have a natural “switch off” button, but even if they do not, their ability to be patient can always be improved. Time spent watching other dogs working or patiently watching any other activity, will always help. There really is no substitute for putting in time to allow the dog to get used to the periods of inactivity.

Mutual trust is essential

If you are picking-up on a moor, the keeper is very likely to want your dogs to range over a large area of ground to pick every possible bird. This might not sound ideal for someone who has just spent months getting his spaniel to hunt close to him! On the other hand, someone who has their dog with them in the butt will want their dog to hunt fairly closely.

You will see (or hear!) a lot of people constantly encouraging their dog to hunt by saying “hi lost/get on” or other words. I personally cast a dog off and expect it to hunt until I tell it not to either by stopping it on the whistle or recalling it in to me. In early training I will set up a retrieve – either a marked one or an unseen one – and send the dog, allowing it to hunt without interference.

I am aiming for a dog that will continue to hunt in an area I have sent it to. If this is done in say, an isolated patch of cover, a field corner or similar, the dog will tend to hunt that area until it finds it. If you interfere with the dog or nag it, you risk them either ignoring you or lifting their head and stopping hunting.

Once a dog will hunt for a retrieve, I will put out up to half a dozen dummies in the same place and continually send the dog back into that area to find them. What I am wanting the dog to do is hunt the area I tell him to even though it thinks it has already found there (which it has). I want it to believe me that there is something else there to be found. On many occasions on a moor you will want a dog to hunt a relatively small area of heather until it finds a missing grouse often covering the same ground until it finds the bird which might well have tucked in.

There are many techniques to get a dog to ‘hold an area’ which I have not got enough space to discuss now, but that ability to get a dog to continue to hunt a specific area on a moor is probably more important than marking or long directional retrieves.

To really enjoy a day on a moor with a dog, you do not need an ‘all whistles and bells, bred in the purple Championship winner to Championship winner dog’. Many of the best dogs I have seen on a moor have not got a pedigree written entirely in red and have not had months of intensive training, but have just been allowed to develop their natural abilities. However, if you have a young dog that is relaxed walking at heel and will sit patiently for long periods and then not get too wound up during brief periods of intense activity, you are well on your way to having a very good companion for the moor.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

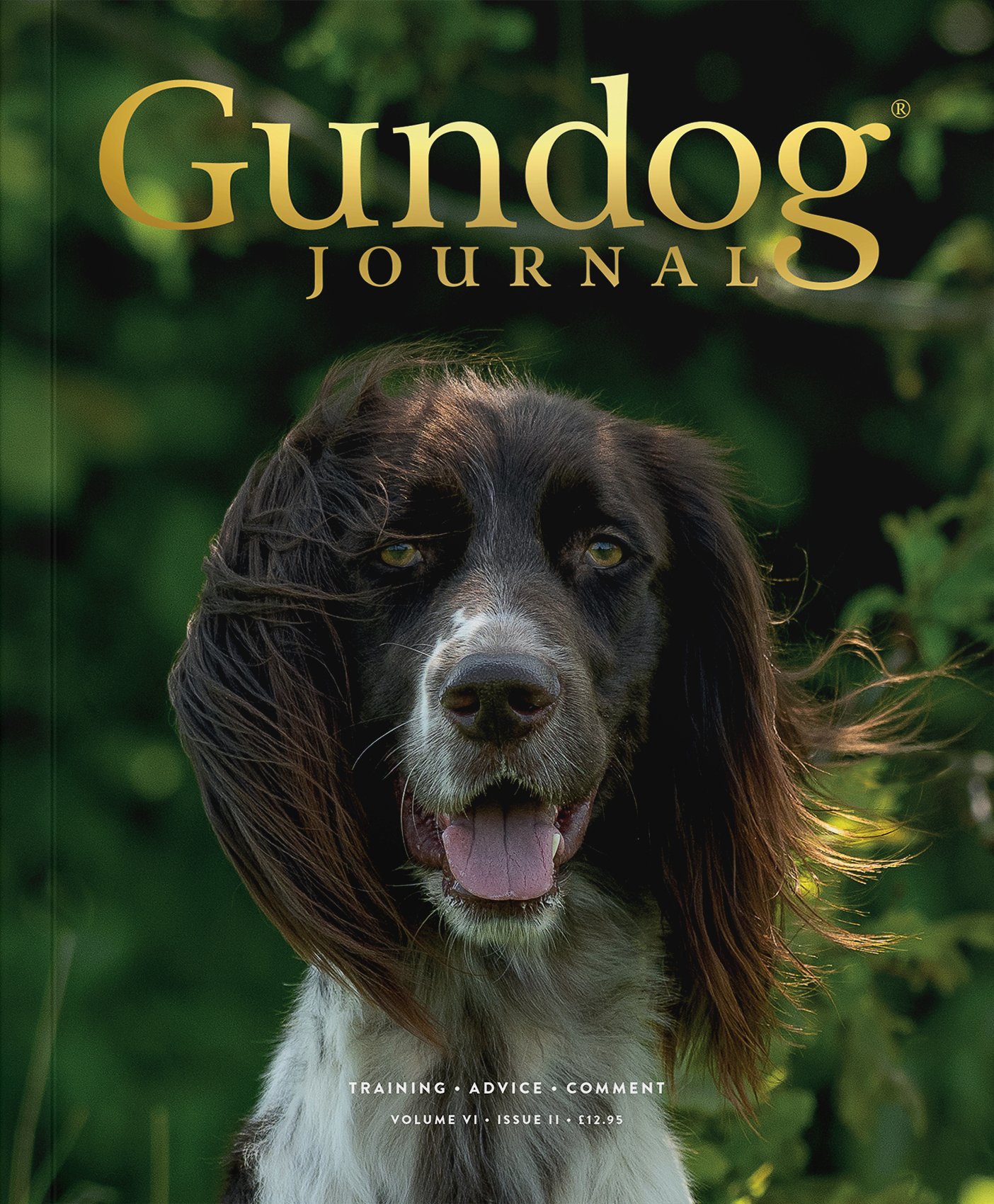

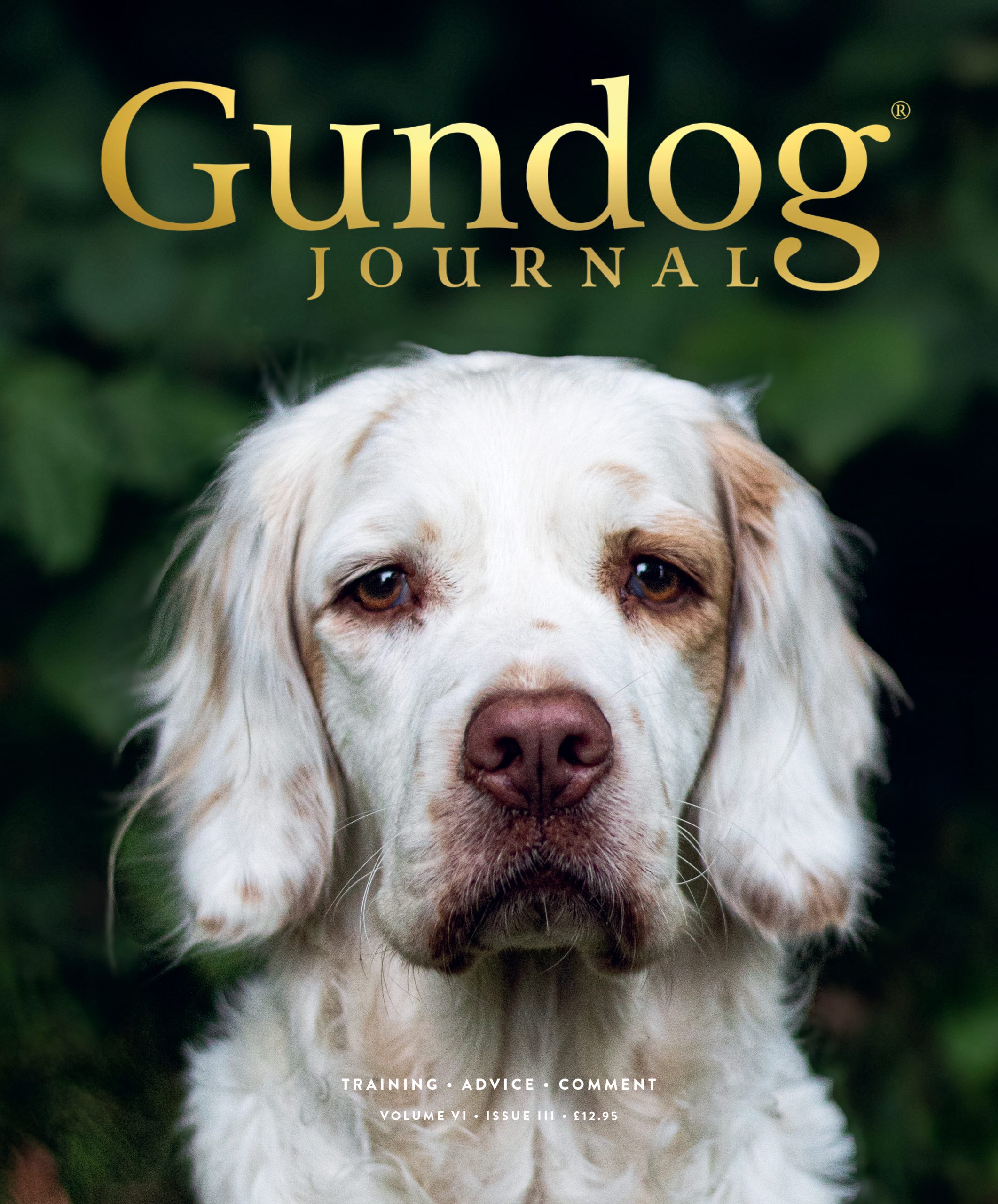

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.