Picking up, a Gun’s view

Poor picking-up practice can be the difference between a good, a bad and an ugly day’s shooting, says Nigel Birt-Llewellin.

On October 25, 2012, I was knocked over by a large yellow labrador at a commercial shoot in Kent. The dog had been sent to retrieve a redleg partridge that was lying, stone dead, on its back some 40 yards in front of me. The bird was the first kill of the day, flying right to left and parallel to the Guns. The dog took my left knee at a full gallop as I was addressing an oncoming covey. I managed to go down on my back, only just keeping control of the gun. The dog barged by my spaniel as it returned past us with the bird – as if to make a canine comment about peg dogs. In a sea of pain, I sat out that drive and the next. A split second later and this could have been a disaster. Sadly, this is just one of many instances of poor picking-up I can recall from over the years.

Almost deadly

During the 27 years I was based in London, I shot with a roving syndicate which used to take days with Ron Thorpe at Wimborne St Giles. We all got on well with Ron and most of us took additional private and corporate days with him. On one such day in the late ’80s, I was on the far left of the line – peg No. 8. Ron was standing with me, talking to his keepers on the radio who were adjusting the beating line as required. A few coveys were slipping out below the end flag-man – barely visible and skimming the freshly drilled wheat as they quartered away towards a collapsed fence to my left. Ron urged me to get stuck in – they were safe and sporting, after all. By the end of the drive, I had three in the bag. Many of the birds had been following the same line to an old fence strainer, some 55 yards from the peg.

Over the next 12 years, I was lucky enough to end up on that peg a few more times; sometimes mastering it, more often not, Ron always cajoling in his gentle way. But it is November 11, 2000 that leaves the greatest impression still to this day.

On this occasion, Ron was at the other end of the line and a new picker-up had taken up position close behind me on peg 8. I went and explained what would happen. With bile rising in my throat, 17 years later I can recall the subsequent sequence of events in minute detail…

The drive started for me with two partridges, typically wide and low. I missed the first but shot the second. A small covey followed, and a right and left joined the bag. I was easing into it nicely. Then another single came on the same line; I was just squeezing the trigger, focused entirely on the bird, when something caught my eye… the picker-up had moved, mid drive, and was standing next to the old strainer. My blood runs cold just recalling it. I stopped shooting. I was retching when Ron arrived. He ascertained what had happened and sent the man home. That man is alive today because God was willing.

The three rules

After retirement from the City, an uncle convinced me to join him in running a small semi-commercial shoot here in West Wales. For the 2010/11 season I agreed to run it under his tutelage, with a view to taking over the following season.

Now, Guns in this area normally have their own dog(s), and expect to pick-up the greater majority (if not all) of what they shoot. By our third shoot day, the Guns had made it abundantly clear that things had to change. Pickers-up were working their dogs from the moment the first bird hit the ground.

The main problem, however, was the field trialers – two of them. They would only pick-up birds which were in the open and dead – their focus on schooling their pupils and not on accounting for every bird shot. I sacked one, and the other never showed again. Morale was very low, and I was in trouble with a whole season in front of me.

The solution to my dilemma first emerged one evening over cigars and brandy. A generous invitation had taken me to a private shoot in England where John, our host, had introduced three strict rules for the pickers-up: 1) no pickers-up are permitted to retrieve a bird until the guests are happy to receive some help; 2) Runners must be picked before dead birds; and 3) the pickers-up must stand at least 200 yards behind the line. With no other changes, his bags had gone from around 250 up to 300. The pickers-up were less distracted during the drives, and could therefore mark more birds and with greater accuracy.

Back in Wales, my contract stated the day would finish at the end of the drive when we passed 500 cartridges, with no guaranteed bag. So far we had been picking up 80–100 pheasants. In the steep-sided valleys of West Wales, I could barely get the picking-up team 100 yards back, but I applied the same rules and our bags immediately rose to 100–120.

No movement, please

On November 24, 2016, I was on a high partridge shoot in Dorset. I commented how relaxing it was to have no movement behind the line during the first drive, and how I regretted not bringing my own dog. The keeper’s reply made a lot of sense: “Any keeper worth his salt knows partridges react to movement,” he stated. “If anyone (or any dog) is moving about during the drive, the birds will split around the Gun directly in front. Besides, there is plenty of time to pick-up between drives”. I was surprised that a commercial operator would be so emphatic.

A stress-free solution

Given the Gun(s) are paying for the day, and pickers-up are being paid, it never fails to amaze me how the latter often seem to go out of their way to aggravate the Guns’ dogs. Tactics to try and avert this (that have all failed) include: asking politely; asking abruptly; asking rudely; and going home half-way through the day. But I have been introduced to the ultimate and completely effective stress-free solution…

Last year I turned down an invitation to shoot at one of England’s very best shoots. Last time I went, in 2006, there were dogs running everywhere during the drives. However, I knew several of the party and offered to load for one of them. The night before, we met up with the rest of the Guns at the local pub. Our team leader’s black lab was sitting patiently at his side (as they do) and before long the conversation turned to picking-up.

“I will be thoroughly shocked if a dog moves tomorrow,” our team leader announced with a mischievous smile. “Most of us shot there a couple of weeks ago. After collecting the keeper’s tip from my fellow Guns, I explained to him that it was being donated to the Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, and that I did not expect my dog to have to compete for retrieves again! That is unless he wanted to keep seeing his tips given to charity.”

The next day I watched the lab carrying two (and three on one occasion) partridges back to his master. I did not see a picker-up move before we had got back into the vehicles to move to the next drive. There were over 300 in the bag at the end of the day. It was a delightful occasion, and I was sorry not to be shooting!

Conclusions

1: We can see that, for health and safety reasons, pickers-up and/or their dogs should not be permitted to move during the drives.

2: We can see that, morally, the pick-up is more effective if left until after the drive has come to an end.

3: We can see that, commercially, Guns are happier when not distracted by the inevitable symphony of whistling and associated chorus of calls when pickers-up work their dog(s) during drives.

4: Finally, we can donate more money to charity. Most shoots raise money for at

least one!

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Gundog Journal

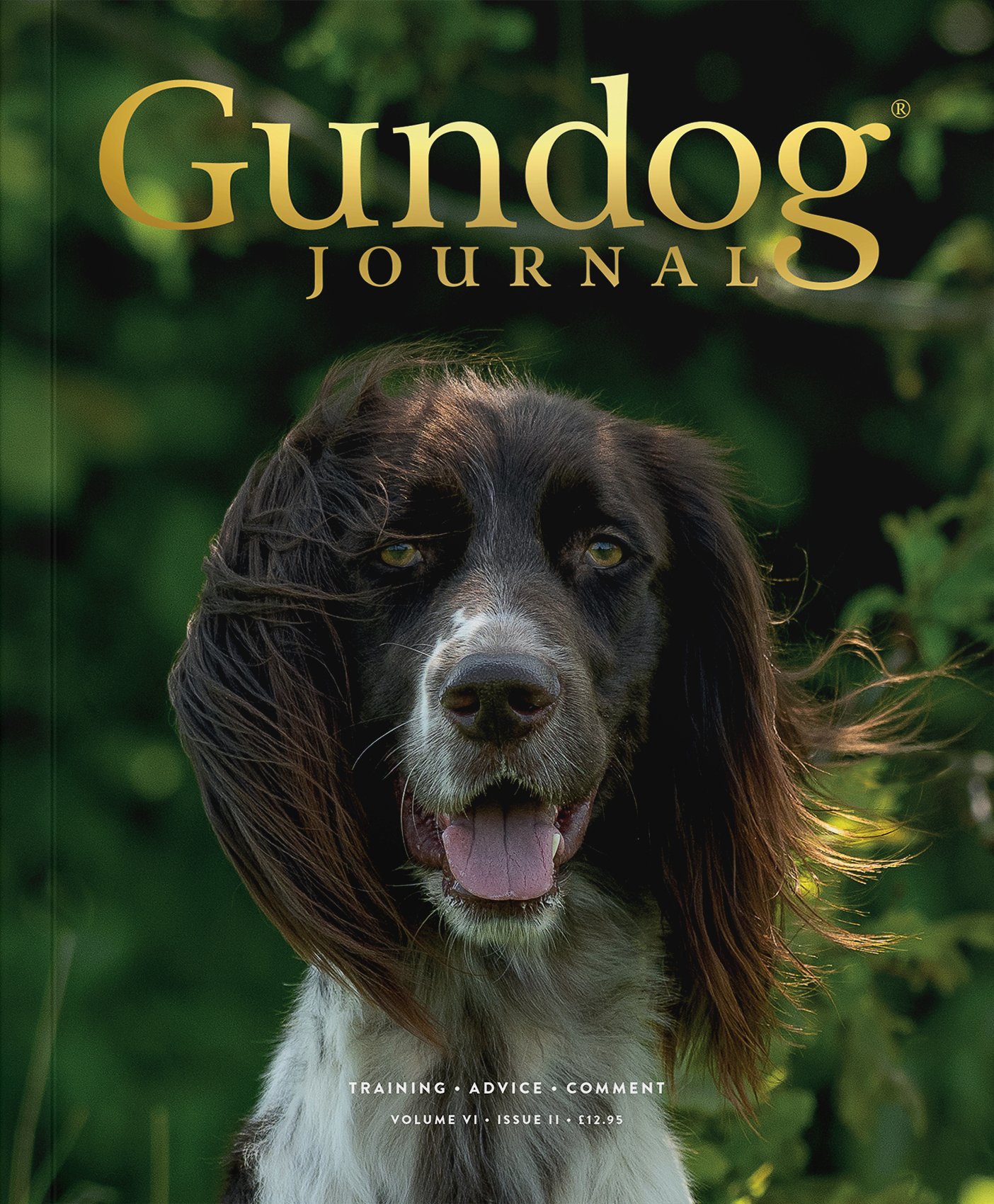

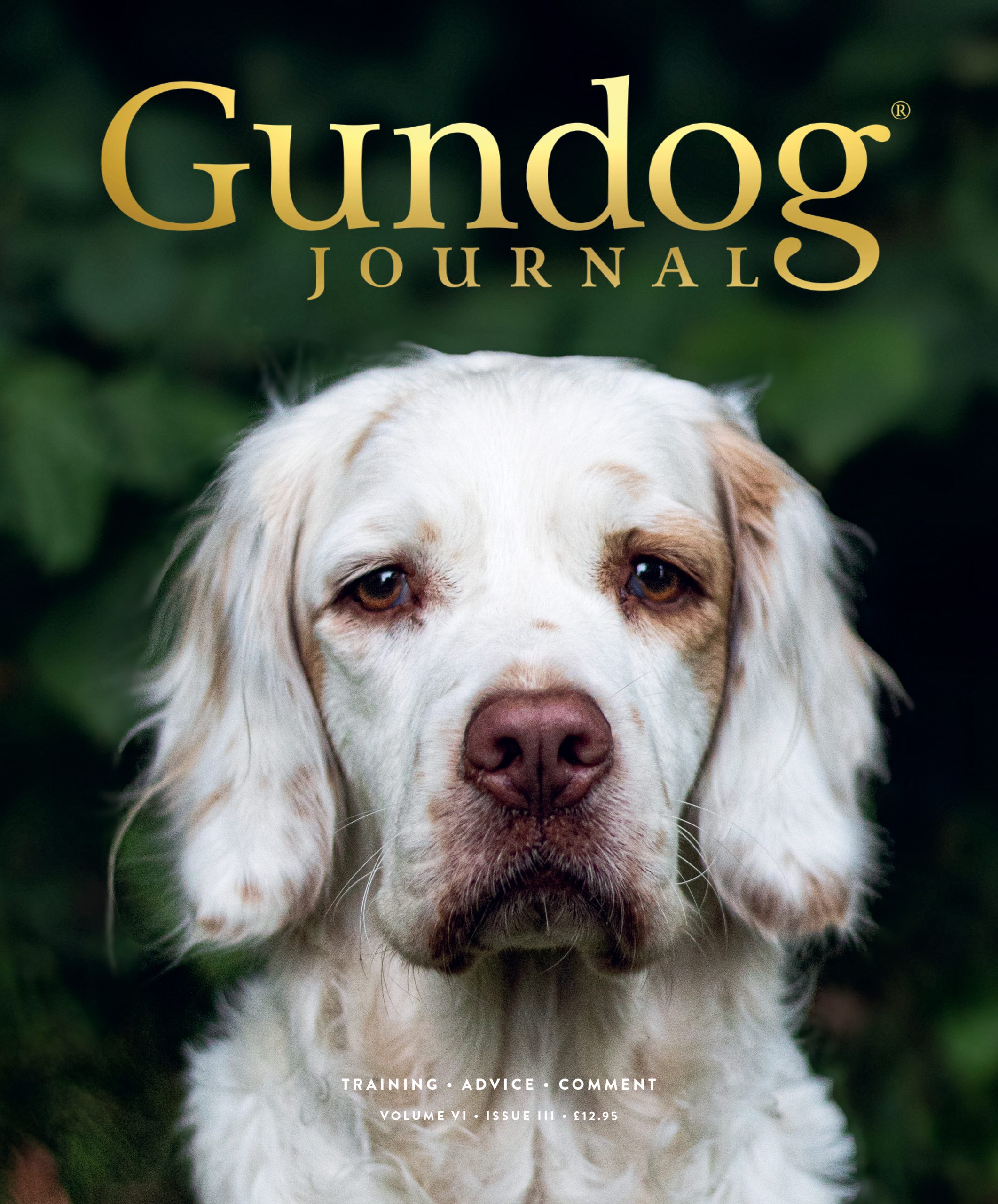

Unlock the full potential of your working dog with a subscription to Gundog Journal, the UK’s only dedicated magazine for gundog enthusiasts. Published bi-monthly, this authoritative resource delivers expert training advice, in-depth interviews with top trainers and veterinary guidance to help you nurture a stronger bond with your dog.

With stunning photography and thought-provoking content, Gundog Journal is your essential guide to understanding, training and celebrating your working dog.

Save 10% on shop price when you subscribe, with a choice of packages that work for you. Choose from Print & Digital or Digital only with each journal delivered directly to your door or via the app every other month, plus access to past issues with the digital back issue library.